By Constance GBEDZO

Risk & Enterprise Development Expert

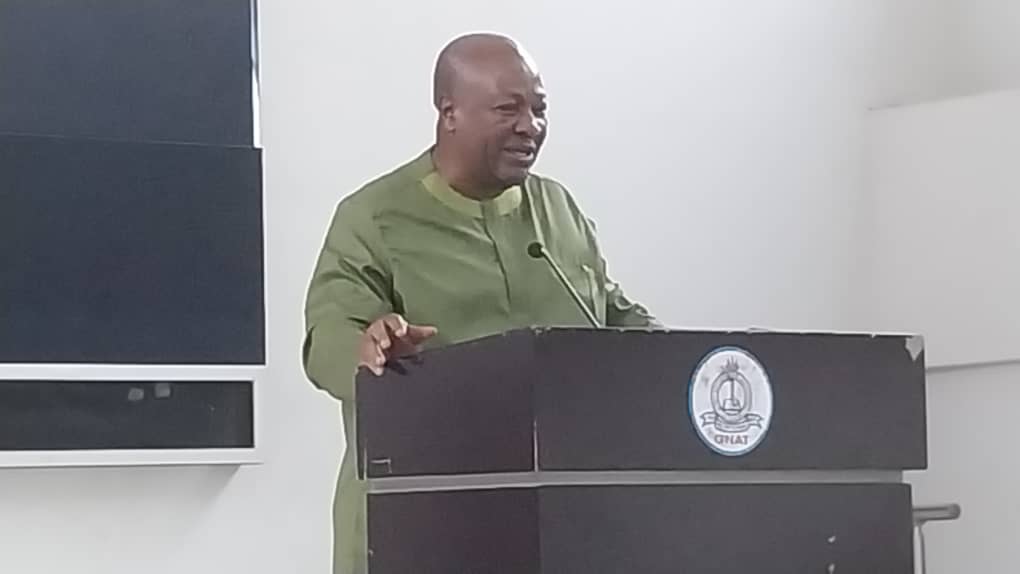

John Dramani Mahama was never the flamboyant and sloganeering person. Indeed, many Ghanaians gave him support for his character of simplicity, openness, honesty and genuineness of purpose. He served as President of Ghana from January 2013 to January 2017, following his completion of the late President John Atta Mills’ term.

This term in office saw a mixed economic performance, marked by initial high growth rates from the oil sector that quickly gave way to fiscal instability and external shocks. His first and only full term in office was characterized by significant investments in infrastructure alongside major macroeconomic challenges that ultimately overshadowed the economic narrative.

The macroeconomic environment then was volatile, characterized by a sharp decline in key indicators after the initial year, culminating in an IMF program. In essence, his term was defined by a transition from high but unsustainable growth in 2013 to an economic crisis characterized by low growth, double-digit inflation, a high budget deficit, and rapidly rising public debt, leading to the country seeking an IMF bailout in 2015.

Economic Performance

The key macroeconomic numbers for John Mahama’s tenure, primarily for the period 2013–2016, based on available data from the government and international financial institutions (figures are typically year-end or averages).

Key Macroeconomic Indicators (2013-2016)

| Indicator | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

| Real GDP Growth (%) | ?7.3% | ?2.9% | ?2.2% | ?3.4% |

| Inflation (%) | ?13.5% | ?17.0% | ?17.7% | ?15.4% |

| Fiscal Deficit (% of GDP) | ?10.1% | ?10.3% | ?6.7% | ?9.3% |

| Public Debt (% of GDP) | ?55.9% | ?70.2% | ?71.6% | ?73.1% |

| 91-Day T-Bill Rate | ?19.2% | ?25.8% | ?25.0% | ?16.5% |

Detailed Analysis of Key Indicators

a) Real GDP Growth Rate: The year 2013 started strongly with growth at approximately 7.3%, benefiting from oil production. Growth in 2014-2015 slowed dramatically to a low of about 2.2% in 2015. This was due to the combined effect of the severe power crisis (Dumsor), fiscal consolidation measures under the IMF, and falling commodity prices (oil, gold, cocoa). Growth in 2016 saw a slight recovery to about 3.4%. The average (2013-2016) GDP growth rate was approximately 3.9%.

b) Headline Inflation Rate: Inflation consistently remained outside the Bank of Ghana’s target band throughout the term. The inflation rate rose significantly from 13.5% in 2013 to peak at about 17.7% in 2015, driven by currency depreciation and the removal of subsidies on fuel and utility tariffs. High inflation eroded real incomes and increased the cost of living for Ghanaians.

c) Fiscal Deficit (% of GDP) (High Indebtedness): Government inherited a high cash-based deficit of 11.5% in 2012. Despite efforts and the IMF program, the fiscal deficit remained persistently high, even after a drop to 6.7% in 2015. It rebounded to a significant 9.3% in 2016 (according to IMF/Post-election reports), reflecting substantial expenditure overruns and failure to meet revenue targets.

d) Public Debt (% of GDP) (Rapid Accumulation); the debt stock increased sharply from approximately 55.9% in 2013 to about 73.1% by the end of 2016. This rapid debt accumulation raised significant sustainability concerns, as the ratio surpassed the widely-accepted threshold of 60% of GDP for a developing country.

e) Interest Rate (High Cost of Borrowing): The interest rate on the benchmark 91-day Treasury Bill surged from 19.2% in 2013 to a high of nearly 26% in 2014/2015, reflecting the high-risk perception by the market due to inflation and the budget deficit. High rates increased the cost of domestic borrowing for the government and businesses.

Infrastructure Development

The most notable success of the Mahama administration was the massive investment in infrastructure development across the country, often referred to as the “unprecedented infrastructure agenda” by his supporters. The government in 2013-2017 undertook a substantial program of infrastructure development. While some projects were initiated before his tenure and completed during his time, others were new initiatives.

Transportation:

Significant projects were undertaken in the road, rail, and aviation sectors. This included the construction and completion of major road networks, the expansion and modernization of the Kotoka and Tamale International Airports, the construction of Ho domestic airport, and investments in maritime infrastructure, such as the expansion of the Tema and Takoradi harbours.

Regarding Interchanges and Overheads, the most notable completed project in this category is the Kwame Nkrumah Interchange in Accra. This a 3-tier interchange (overpass, roundabout, and an underpass) officially commissioned in November 2016. This project replaced the congested Kwame Nkrumah Circle roundabout, significantly easing traffic flow for over 80,000 vehicles daily traveling on major routes connecting the city centre.

Concerning Harbours and Bridges the following projects were undertaken:

- Tema Port Expansion: Major investment and initial works began on the deep-water harbor expansion project to increase container handling capacity.

- Ankobra Bridge: The Ankobra River Bridge was fixed and restored and Buipe, Daboya, and Yapei Bridges; Plans and initial works for the rehabilitation of these critical bridges over the Volta River were advanced.

About Roads, a number of major urban and trunk road projects were completed or continued under the administration:

- Awoshie-Pokuasi; a 14-kilometer road was completed, and included associated infrastructure, linking major suburbs.

- Achimota-Ofankor; a major project involving the expansion of the road into an urban highway, completed and commissioned.

- Tetteh Quarshie-Adenta, completed major works and expansion on a vital urban highway.

- Sofoline Interchange; significant progress was made on this project, though the full Interchange project had been ongoing from a previous administration.

- Fufulso-Sawla Road; a significant trunk road project in the north of the country, Northern/Savannah Regions

Health Facilities and Hospitals:

Major infrastructure investments were directed towards the expansion and upgrade of healthcare facilities, including the construction of new regional and district hospitals.

- Greater Accra Regional Hospital; (Ridge Hospital Expansion) Phase I and II of the major expansion and upgrading project were completed, transforming it into a modern 420-bed facility.

- University of Ghana Medical Centre (UGMC); Construction of the 617-bed national teaching and quaternary hospital was largely completed, though it was not fully operational before the end of the term.

- Bank of Ghana Hospital; a new, high-specification tertiary hospital built using public funds (Bank of Ghana reserves).

- Regional Hospital; Wa (Upper West Region); the 160-bed hospital was completed and commissioned to serve the region.

- Maritime Hospital; new specialised hospital for the port and maritime sector.

- District Hospitals – Dodowa, Kumawu, Fomena, Abetifi, Tepa, Nsawkaw, Konongo, etc.; the government initiated and/or completed a number of new 120-bed capacity district hospitals across various districts.

Education:

Major infrastructure investments were directed towards the construction of new Community Day Senior High Schools (SHS), known as the E-Blocks; a major signature project in the education sector was the construction of new high schools to address the challenge of overcrowded existing schools and to meet the increasing demand for secondary education. E-Blocks Construction of 200 new Community Day Senior High Schools (known for their distinctive E-shaped block design). A number of these schools were completed and commissioned during the period, providing infrastructure to accommodate thousands of students.

Energy:

The government prioritized addressing the power crisis, known locally as “Dumsor” (a continuous irregular power supply), through investments in power generation capacity. This effort, while eventually yielding results, came later in the term. The strategy focused heavily on increasing thermal generation capacity through Independent Power Producers (IPPs). The key power generation projects commissioned or brought online during this period added hundreds of megawatts (MW) to the national grid:

Thermal Power Projects

The administration’s total added capacity from completed and commissioned projects like Karpowership, AMERI, T3, and KTPP provided a substantial injection of over 800 MW into the national grid, which was instrumental in stabilizing power supply toward the end of the ‘dumsor’ crisis.

- Karadeniz Powerships (Karpowership) Floating Power Plant, Initial 225 MW (out of a 450 MW total contract); the first powership, the Ay?egül Sultan, was a fast-track solution to the energy crisis, docking at Tema to inject power into the grid under a 10-year agreement with ECG. Commissioned (2015)

- AMERI Power Plant Thermal (Gas/Diesel) 250 MW; brought in under an emergency power agreement (Africa and Middle East Resources Investment Group) to rapidly bridge the generation gap caused by gas supply issues and low hydro levels. Commissioned (2015)

- Takoradi T3 Combined Cycle Power Plant; Thermal (Combined Cycle) 132 MW This expansion of the Takoradi Thermal Power Station was completed to augment the country’s power generation capacity, designed to run on gas, light crude oil, or diesel. Completed/Commissioned (2013/2014)

- Kpone Thermal Power Plant (KTPP); Thermal (Gas/Diesel) 220 MW Constructed by the Volta River Authority (VRA), this plant significantly boosted VRA’s thermal generation capability near the Tema area. Completed/Commissioned (2015)

- Cenpower Kasoa Power Plant Thermal (Combined Cycle) 350 MW; this major Independent Power Project was significantly advanced during this period, though it was commissioned after the end of the administration’s term. Initiated/Advanced

Renewable and Distribution Projects

- Solar Systems: Smaller-scale solar power projects were pursued, including the VRA’s 2 MW solar system at Navrongo. Thousands of solar photovoltaic (PV) systems were also installed in remote rural communities under various projects.

- Optic Fibre Infrastructure: To support the national grid and other communications, about 800 kilometers of optic fibre infrastructure were deployed along the eastern corridor from Ho to Bawku with a link from Yendi to Tamale.

Gas Processing and Infrastructure

The John Mahama administration made significant investments in gas infrastructure, particularly in the Western Region, to transition power generation from expensive light crude oil to cheaper, indigenous natural gas and to ensure energy security. Here are the details of the major gas projects undertaken:

Western Corridor

This was the cornerstone of the gas strategy, executed by the Ghana National Gas Company (GNGC), which was established by the previous government and became operational under the Mahama administration.

- Atuabo Gas Processing Plant (GPP) Commissioned (2015) A gas processing plant with a design capacity of 150 MMscfd (Million Standard Cubic Feet per day), expandable to 300 MMscfd. The plant processes raw gas from the Jubilee Field to produce pipeline-quality lean gas (for power generation), LPG, and condensates.

- Gas Pipelines (Onshore & Offshore) Completed (2013-2014). Construction of the associated pipeline network: Offshore Pipeline: 58 km, 12-inch diameter line transporting raw gas from the Jubilee and TEN fields to Atuabo-Takoradi (AT) Onshore Transmission Pipeline: 110 km, 20-inch diameter pipeline transporting the processed sales gas from Atuabo to power plants in the Western Power Enclave (Aboadze).

- Esiama-Prestea Lateral Pipeline A 75 km, 20-inch diameter onshore gas transmission pipeline that extends the network inland from Esiama towards Prestea and its mining enclave for potential industrial gas users. Commissioned (2016), with commercial operations starting in 2017.

- Takoradi Distribution Station (TDS) Expansion: Expansion of the station to increase capacity from an initial 130 MMscfd to 405 MMscfd to handle increased gas flows, completed. This enabled the efficient distribution of gas to the thermal power plants. The completion and commissioning of the Atuabo Gas Processing Plant and its related pipelines was a major milestone, marking Ghana’s transition into the “gas era.”

Sankofa Gas Project (Offshore Cape Three Points – OCTP)

The administration played a critical role in finalizing the agreements and initiating this massive integrated oil and gas development.

- OCTP Integrated Project Groundbreaking Ceremony (2016): The agreement was signed in 2015. A major integrated oil and gas project, being undertaken by ENI (Italy’s largest oil company) and Vitol Energy, to develop the Sankofa and Gye Nyame

- Gas Supply Potential: Expected first gas flow in 2018. The project was specifically designed to provide 180 MMscf/d of non-associated gas for a period of 20 years, capable of generating about 1,000 MW of electricity.

- Gas Infrastructure: Construction commenced in the period. The plan included onshore gas receiving facilities at Sanzule to tie into the existing Ghana Gas pipeline network, ensuring the gas could reach both the Aboadze and Tema power enclaves.

- Ghana Gas Company: The administration supervised the initial operations and full commercialization of the Ghana National Gas Company (GNGC), the state-owned entity responsible for the gas infrastructure. Cabinet approved the Gas Master Plan in 2016, a strategic document intended to guide infrastructure expansion and delivery requirements for the country’s growing gas industry.

- Regulation: Supervised the full establishment and operationalization of the Petroleum Commission as the upstream sector regulator.

Social Protection Measures

The Mahama administration continued and, in many cases, expanded key social protection interventions, aligning with Ghana’s broader National Social Protection Policy framework. These include the Livelihood Empowerment Against Poverty (LEAP), School Feeding Programme (SFP), National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), Labour-Intensive Public Works (LIPW), and Capitation Grants.

On job creation, Mahama administration focused its job creation strategy on the massive infrastructure investment and Local Content Policies in the nascent oil and gas sector. The primary method for job creation was linking large-scale national projects to local employment and industrial growth.

- Infrastructure-Led Employment: The administration emphasized using major public infrastructure projects as an employment engine across various sectors: roads and transport, hospitals, Port Expansion projects, etc. created both direct jobs (engineers, technicians, laborers) and indirect jobs in related supply chains (cement, steel). Gas and Power Sector: Projects like the construction of the Atuabo Gas Processing Plant and its associated pipelines employed thousands of workers across all skill levels, from engineering to construction and operations.

- Local Content and Participation Policy: The government passed the Petroleum (Local Content and Local Participation) Regulation (L.I. 2204) in 2013. This law was designed to maximize Ghanaian participation in the oil and gas industry.

Failures and Challenges

Despite the infrastructure focus, the economic climate was defined by severe macroeconomic difficulties. Ghana faced persistent and large fiscal deficits. Public sector wages, particularly after the implementation of the Single Spine Salary Structure (SSSS) for public sector workers, grew significantly, contributing to high government expenditure. This necessitated substantial borrowing, leading to a surge in the public debt-to-GDP ratio.

The Ghanaian Cedi experienced significant depreciation against major international currencies, particularly the US Dollar. This, combined with fiscal pressure, fueled high inflation rates, severely eroding the purchasing power of citizens. The economy was negatively impacted by falling global prices for Ghana’s primary exports—gold, cocoa, and crude oil—which reduced foreign exchange earnings and government revenue.

His commitment to social protection sought to mitigate the effects of the harsh economic climate on the poorest segments of the population, although the scale of the macroeconomic challenges often overshadowed the positive impact of these welfare programs.

The prolonged and intermittent power supply crisis, a hallmark of Mahama’s, severely hindered industrial and commercial productivity, leading to business closures, job losses, and contributing to the overall economic downturn. The negative economic impact of dumsor was widely cited as a major failure.

Due to the deteriorating fiscal situation and the resulting loss of access to international financial markets, the government eventually entered into a three-year Extended Credit Facility (ECF) program with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 2014/2015 to restore macroeconomic stability.

Beyond 2016, the subsequent policy discussions from the same political grouping, though outside the 2013-2016 term, indicate a continued focus on structural solutions to job creation, including: The “Big Push”: A proposed $10 billion accelerated infrastructure plan designed to create massive employment opportunities.

Digital Jobs: Initiatives like the One Million Coders Programme to focus on technology-driven job growth. 24-Hour Economy: A deliberate policy to encourage businesses to operate around the clock to maximize productivity and create an extra two shifts of jobs.

The writer is a Risk & Enterprise Development Expert

The post John Dramani Mahama: A retrospective on “unprecedented infrastructure agenda” appeared first on The Business & Financial Times.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS