By Samson ADEPOJU

The landscape of Black educational empowerment is being written in real-time across two continents, through two dramatically different stories that reveal the gap between vision and execution, between dreams deferred and dreams delivered.

The crisis in Delaware

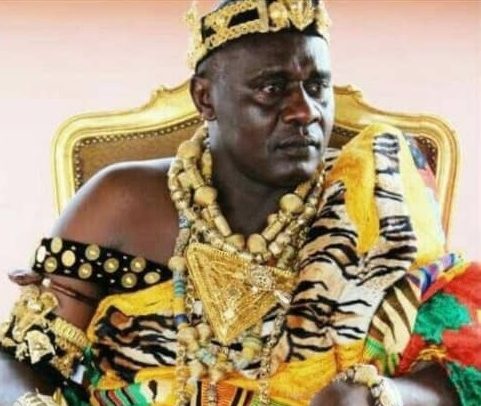

Dr. Umar Johnson’s Frederick Douglass Marcus Garvey (FDMG) Academy stands on the precipice of collapse. The self-proclaimed “Prince of Pan-Africanism” faces an August 25th deadline to save his Wilmington, Delaware campus from sheriff’s auction due to unpaid fees and utilities. The irony is stark: a project designed to liberate Black boys from what Johnson calls “mis-education” may itself become a lesson in institutional failure.

For over a decade, Johnson has rallied supporters around his vision of a Pan-African educational institution. He positioned the academy as more than a school, but rather, as a cornerstone of Black independence and cultural pride. Yet today, with frozen bank accounts following alleged hacking attempts and mounting financial obligations, the project hangs by a thread.

Johnson’s response reveals both his strengths and weaknesses as a leader. He frames the crisis as evidence of systemic targeting, claiming the city escalated vacant property fees from $5,000 to $12,000 annually to force foreclosure.

While his supporters see validation of his anti-establishment message, critics point to a pattern of financial opacity and management challenges that have plagued the project from its inception. (Keep in mind residents of Long Island, New York pay over $12,000 a year in school taxes whether you have children or not, so should Dr. Umar, a celebrity psychologist be struggling to pay that fee? Maybe he needs more clients or patients to treat).

The Success in Ghana

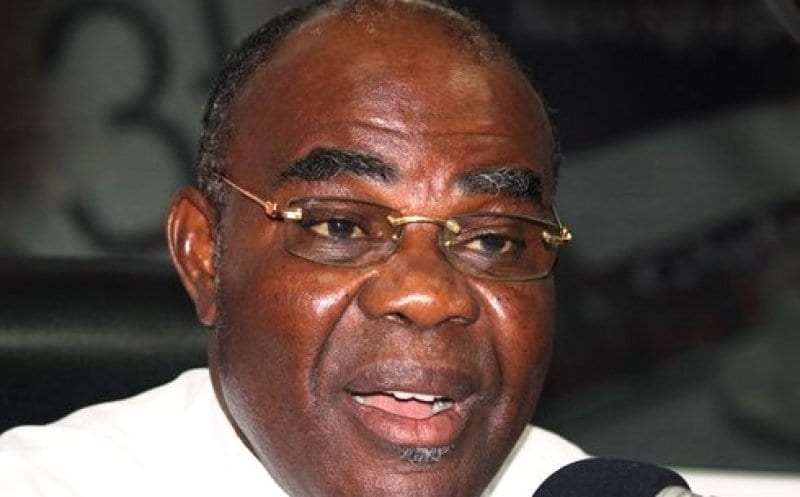

Meanwhile, 5,000 miles away, a different story unfolds. Jimmy Quansah and his sister Vida Selma Koomson have quietly built something remarkable: DestinyFaith Christian International School, which has grown from a single village classroom to an educational powerhouse serving 255 students in just four years.

Their secret weapon isn’t ideology, it’s integration. Seven-year-olds learn English while mastering hair braiding. Teenagers study mathematics while designing fashion and building furniture. This “Learn & Earn” model doesn’t just educate; it creates immediate economic value for students and their families.

The numbers tell the story: 255 students enrolled with hundreds on the waiting list, 19 full-time local staff employed, and multiple vocational tracks generating real income. Where Johnson’s academy struggles with sustainability, the Ghana school has cracked the code on self-sufficiency.

The Contrast in Approaches

The divergent paths of these two educational ventures illuminate fundamental questions about Black empowerment and institutional building.

Vision vs. Execution: Johnson’s Pan-African rhetoric resonates powerfully, but grand visions require practical execution. The frozen accounts and mounting debts suggest a disconnect between aspirational messaging and operational competence. In contrast, the Ghana school’s founders built steadily, focusing on sustainable growth over revolutionary rhetoric.

Community Engagement: Johnson positions himself as leading a movement, rallying supporters through crisis and controversy. The Ghana model embeds itself within existing community structures, hiring locally and creating immediate economic benefits that build organic support.

Financial Transparency: The FDMG Academy’s financial struggles raise questions about donor trust and accountability. When supporters invest in a dream, they expect clear communication about how their money is used. The Ghana school’s growth trajectory suggests a more transparent, trust-building approach to resource management.

Economic Sustainability: Perhaps most tellingly, the “Learn & Earn” model addresses a critical flaw in many educational initiatives: sustainability. By teaching immediately marketable skills alongside academics, the Ghana school creates a pipeline of economic opportunity that supports both students and the institution itself.

Lessons for Black Educational Empowerment

These parallel stories offer sobering lessons for anyone committed to Black educational advancement:

Start Small, Build Smart: The Ghana school’s four-year journey from classroom to 255-student institution demonstrates the power of organic growth. Rather than announcing grand plans, they built incrementally, proving concept before expanding.

Economics Matter: Educational empowerment without economic empowerment is incomplete. The “Learn & Earn” model recognizes that families need immediate economic benefits to sustain long-term educational investment.

Operations Over Oratory: Inspiring speeches can mobilize people, but institutional success requires mundane competencies: financial management, regulatory compliance, and transparent communication. These unsexy skills often determine whether visionary projects survive their first crisis.

Accountability Builds Trust: Donors and communities invest in people they trust. Transparency about challenges, clear communication about resource use, and demonstrated results build the social capital necessary for sustainable institutions.

The Broader Context

Both stories unfold against the backdrop of persistent educational inequities affecting Black communities globally. Johnson’s frustration with American public education is legitimate, achievement gaps, disciplinary disparities, and cultural disconnection plague many Black students. Similarly, the Ghana school addresses real educational deficits in rural communities often overlooked by government resources.

The question isn’t whether these problems deserve attention, they absolutely do. The question is which approaches prove most effective at creating lasting change.

Looking Forward

As Johnson faces his August 25th deadline, his supporters rally with protests and donations. Whether the FDMG Academy survives this crisis may depend less on the passion of his rhetoric than on his ability to demonstrate the practical competencies that institutional success requires.

Meanwhile, the quiet success in Ghana offers a different model: that revolutionary change sometimes comes not through revolutionary methods, but through revolutionary results. By teaching students to earn while they learn, the Quansah-Koomson partnership has created something radical in its own way, a sustainable path from education to economic empowerment.

The fate of both institutions will be determined in the coming months. But their contrasting trajectories already offer valuable lessons about the difference between building movements and building institutions, and why Black educational empowerment may require both visionary leadership and exceptional execution.

For communities watching these stories unfold, the message is clear: dreams of educational liberation are worthy and necessary, but they must be grounded in the practical realities of financial management, community building, and sustainable growth. The future of Black education may depend not just on our ability to envision transformation, but on our commitment to the unglamorous work of making transformation real.

The writer is a Senior Communications Consultant

The post Two paths to black educational empowerment: A tale of promise and peril appeared first on The Business & Financial Times.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS