Daniel did not understand what tuberculosis (TB) was, and his 11-year-old mental reasoning could not grasp the complex world of the TB-causing germ and its complications that the lady doctor was pointedly explaining to his mother.

He barely listened anyway, not only because her voice was barely audible to him through the face mask she wore, but also because the pounding in his head would not stop.

He had been having very bad headaches. The deep-seated coughing bouts that had started about three months ago, exacerbated the headache a million times more. The feeling was as if his head exploded with every coughing effort, while at the same time, he struggled to bring up the viscous phlegm that he could feel accumulating deep within his chest.

A nauseating wave crawled over his stomach, and he puked, making a messy spill on the bed, and disrupting the doctor’s discourse with his mum.

Both adults were visibly upset. They pulled him up while his mother gently rubbed his back as the vomit-induced spasms rocked his upper chest. The doctor was shouting for the nurse to come over. More hands were frantically propping his head up, and palpably trying to ease his discomfort.

He could sense that this was going to be another long day and had never felt so miserable in his life. Daniel has developed tuberculous meningitis, which is a severe form of TB that indicates involvement of the central nervous system.

Specifically in his case, this form of TB had invaded the layer of tissue that covered his brain, hence the severe headache and vomiting that he was experiencing.

TB is an ancient disease. Archaeological evidence of human TB was noted in Egyptian art and mummies from thousands of years ago, corroborating the primeval origins of the disease. In ancient Greece, TB was aptly described by Hippocrates, who noted the fatal outcomes of the disease especially among young adults.

Through the centuries, the epidemic wave of TB ravaged lives throughout the world but it was only in 1720, that a French military surgeon, Jean-Antoine Villemin, convincingly demonstrated the infectious nature of TB. More than a century later, Robert Koch, the great pioneer of the study of bacteria, conclusively established the TB-causing pathogen, mycobacterium tuberculosis, as the aetiological agent of TB. His ground-breaking discovery was announced to the Society of Physiology in Berlin on 24 March 1882, marking a milestone in the fight against TB.

TB sadly remains a global public health problem in these modern times, affecting all countries and all age groups. Worldwide, it is the second leading infectious cause of death after COVID-19. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO),10.6 million people fell ill with TB worldwide, and a total of 1.3 million people died from TB in 2022.

This translates to about 30,000 people falling ill with TB and over 3000 succumbing to the disease each day. Over 80% of these TB cases and deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

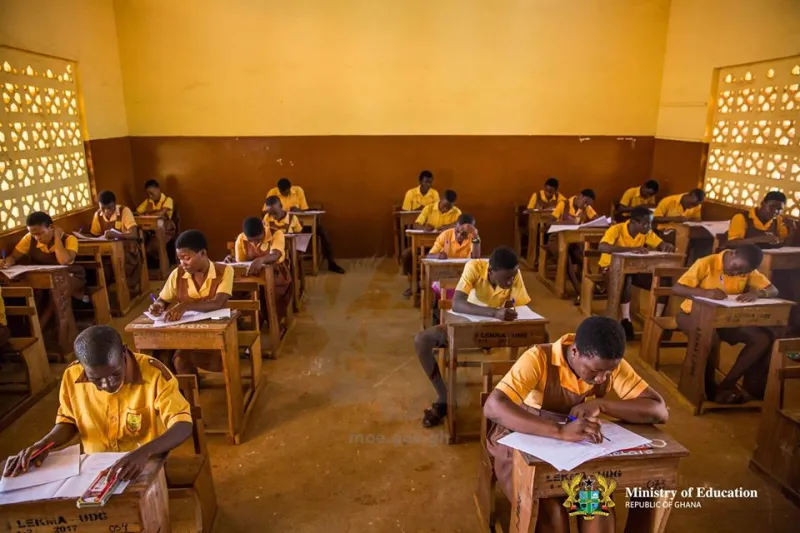

TB most often affects the lungs, spreading through the air when infected people cough, sneeze or spit, and so those affected with lung disease pose the greatest risk of transmission to others. The tiny particles containing the TB-causing bacteria that are released after an infected person coughs can stay suspended in the air for hours in the absence of adequate air movement, so predictably, TB disease is prevalent in environments with over-crowding and poor ventilation. Therefore, congregate settings like prisons and slums are hotspots for TB disease. Once the germ is inhaled, it seeds into lung tissue, but becomes dormant if the person’s immune system is competent. This is considered latent TB, and most persons do not show any symptoms or sign of TB disease as their immune system is robustly able to contain the bacteria.

However, if the body’s immune system is weakened, the TB-causing bacteria are re-activated and they multiply and potentially spread to other parts of the body causing clinical features of disease.

Those at high risk of developing TB disease therefore include babies and children but likewise, medical conditions which compromise immunity such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), diabetes, cancer, chronic kidney conditions and malnutrition puts affected individuals at risk for TB. Social habits like smoking and excessive alcohol intake have also been found to increase the risk of progression to TB disease.

TB disease unfortunately can be debilitating. With lung disease, chronic cough is usually prominent. Infected persons may also experience unintentional weight loss, fever, fatigue, drenching night sweats, coughing up of blood, chest pain and poor appetite.

In children, presenting features of TB may include faltering growth or malnutrition. The symptoms and signs that indicate spread to other parts of the body may depend on the specific body part involved.

Thus, for example, persistent headache, vomiting and neck stiffness may suggest central nervous system involvement whereas back pain from a bony deformity of the vertebrae of the back (gibbus) may indicate involvement of the spine.

TB is curable. Early treatment is crucial as the disease course can be fatal without treatment. Treatment is usually initiated after the diagnosis is confirmed by rapid diagnostic testing on clinical specimens, most commonly on sputum. These have high accuracy and complement the standard imaging modalities accessible to the clinician.

Of note, TB is particularly difficult to diagnose in children as they are not often able to cough up a good quality sputum to be tested. Stool testing of TB is therefore one of the newer approaches recommended by WHO for children who are unable to cough effectively.

The conventional first-line medications used for treating TB include isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol and treatment regimens vary from four to twelve months depending on the severity of disease and whether disease is localised within or outside of the lungs.

TB-causing bacteria which are resistant to rifampicin, isoniazid and other specified antibiotics are usually designated as drug-resistant TB. TB Drug resistance is regarded as a public health crisis by the WHO, and it emerges when TB medicines are used inappropriately, through incorrect prescription by health care providers, poor quality drugs, or patients stopping treatment prematurely.

Those with drug-resistant TB are usually more difficult to treat and require medications which are far more expensive to procure. According to WHO, only about 2 in 5 people with drug-resistant TB accessed treatment in 2022, meaning that many cases remain undetected or untreated.

The good news is that TB is preventable. The WHO estimates that global efforts to combat TB have saved an estimated 75 million lives since the year 2000. However, poverty, HIV infection, drug resistance, and dwindling global funding are important challenges. Moreover, the TB preventive vaccine (BCG) given to babies at birth confers protection against severe forms of TB that occur outside of the lungs but does not fully protect against lung infection, and so, it is not enough to end TB. To end TB, we must do more. It is imperative that countries should increase case detection rates by strengthening point-of-care TB testing, scale up preventive treatment options for all TB contacts and providing evidence-based shorter but effective treatment regimens.

The WHO End TB strategy aims to curtail the epidemic by 2035 and has set ambitious indicators that include a 95% reduction in deaths and 90% reduction in TB incidence. By expanding the scope of interventions for TB care and prevention, engaging stakeholders for bold impactful policies and pursuing new scientific knowledge and innovation, these aims may be achieved.

As LMICs like Ghana align their action plans to these targets, the budget gaps faced by their national TB programmes (NTP) compound the challenge. In Ghana, 44,000 persons developed TB disease including 6800 children in 2023.

The NTP however was notified of only 19,081 TB cases, and 824 childhood TB cases. This huge gap in detection rates means more needs to be done locally and the NTP is expediting collaborative efforts with national stakeholders to aggressively pursue contact tracing, intensify case-finding, promote TB preventive treatment, and widen community engagement and outreaches.

Furthermore, a prime focus in 2024 is to improve detection rates in children, as Ghana’s 5% childhood TB rate is well below the projected estimate of 10%. Accordingly, the NTP has commenced stool sampling for TB testing as stools are far easier to collect in young children, while currently revising the national childhood TB guidelines to reflect these changes in diagnostic algorithms.

Myths and misconceptions unfortunately surround TB care, aggravating stigma and alienating patients who suffer from TB. So, it is important for public education and media advocacy to continue. A strong political will from all arms of government, along with commitment towards an urgent investment in resources will help the NTP to scale up its activities and improve access to testing and care.

Simple sustained efforts at every level can be adopted and strengthened by everyone including healthcare workers and non-healthcare workers. In communities, a person diagnosed with TB should where possible, avoid sleeping in the same room with household members particularly with children under five years of age. Contacts of persons diagnosed with TB should ask a healthcare worker about TB preventive medicine. Good cough etiquette should be practised, and patients should use a handkerchief or tissue to cover the mouth and nose when sneezing or coughing. Hand hygiene should be routinely done.

In healthcare settings, all efforts should be made to minimise transmission. Triage of patients in a queue should direct flow to avoid interaction of coughing adults with vulnerable patients such as the very young or the elderly. Coughing adults should be offered masks and transferred to well-ventilated waiting areas.

Likewise, well-ventilated designated areas in health facilities or “cough booths” may be constructed in a suitable space away from clinical areas where patients can produce sputum samples when required to do so by their physicians. Clinical consulting rooms should be adequately ventilated.

Back to Daniel, who remarkably survived the initial ordeal and was well enough to be discharged home. He has almost completed his treatment course and he feels like a new person each day. The coughing had long eased, the excruciating headaches are a thing of the past, and his nutritional profile has improved remarkably. The return to normalcy seems to have ignited a new release of life in his being.

Even his teenage brain can deduce that death lingered close for a while, but at the right place, he got access to treatment. He keeps his monthly appointment at the local health centre and dutifully reminds his mum to give him his daily medications every morning.

He had long since retook his spot as the neighbourhood goalkeeper among his footballing peers. His close friends crave the attention of playing as strikers or midfielders, but he comfortably prefers the lone moments at the goal post. Yet when the ball is heading towards his domain, and the wild frenzy of the game is coming his way, he embraces the thrill and lurches forward to stop that ball from scoring.

No ball gets past Daniel. That’s his mantra, and this momentum drives his tenacity. He has learned to fight TB, and he believes anything is possible. So last weekend, when his team was once again on the pitch, and the opponent made a move, his impeccable goal-keeping skills flawlessly saved the day.

His friends hugged him and lifted him up in the air. The hero of the hour. He can’t stop smiling. They can’t stop smiling either. It is now his happiness which is contagious, not the disease.

The theme of this year’s World TB Day (24 March 2024) is ‘Yes! We can end TB!’. It conveys a message of hope that getting back-on-track to turn the tide against the TB epidemic is possible. The emphasis is on turning commitments into tangible actions. The theme is a call for the resilience we are to show as a people – Yes! We Can End TB. The bold optimism that echoes in this theme is exquisitely conveyed in the words of the WHO Director-General, Dr Tedros Ghebreyesus, who reminds us all that the onus of ending TB should lie with this generation.

“For millennia, our ancestors have suffered and died with tuberculosis, without knowing what it was, what caused it, or how to stop it. Today, we have knowledge and tools they could only have dreamed of. We have political commitment, and we have an opportunity that no generation in the history of humanity has had: the opportunity to write the final chapter in the story of TB”

Can we end TB? Yes, we can.

Dr. Yemah Mariama Bockarie is a Senior Specialist Paediatrician and a Paediatric Infectious Disease sub-specialist at the Cape Coast Teaching Hospital. She is a member of the Paediatric Society of Ghana.

The post Can we end TB? Dr. Yemah Mariama Bockarie writes appeared first on Citinewsroom - Comprehensive News in Ghana.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS