The queue snakes around the block and each day it gets longer: hungry residents of Heliopolis, São Paulo’s largest favela, waiting in line for the handout that will keep them going until the next morning.

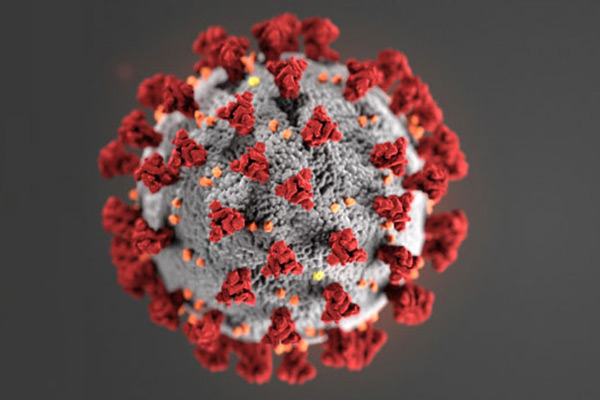

They are given a bowl of pasta with meat and a portion of rice, two packets of biscuits and a carton of milk, shared between a whole household and usually their only meal of the day. Before the pandemic, 300 people would queue up here. Now it is over 1,000, and the charity that runs it has 650 others across São Paulo.

“The vast majority of people who live in the favelas work in the informal economy, as cleaners in homes or helping to bake cakes, so when businesses close or houses stop using them, they feel the impact,” says Marcivan Barreto, the local co-ordinator.

“You see people queuing up at 03:00 for food. I’m very worried that as the pandemic continues, a hungry father will start looting supermarkets. When you’re starving, despair hits.”

During the first wave of the pandemic, Brazil’s government introduced emergency relief, known as “coronavouchers”. More than 67 million people received a monthly sum of 600 reais (£83; $107, at the time).

It was the biggest single injection of financial aid in Brazil’s history, introduced by a president, Jair Bolsonaro, who had previously railed against welfare spending. It pushed extreme poverty to its lowest level since the 1970s – and boosted the president’s support.

But the relief was temporary. With ballooning public debt, the government first suspended the programme and then reintroduced it but at a far lower level of 250 reais and for fewer people.

The drop in aid has hit Luciana Firmino and her family hard. She and her husband now depend on the food handout to feed their five children, living in a cramped couple of rooms in one of the favela’s narrow alleyways.

When the pandemic hit, she lost her job in a manicure studio and her husband’s occasional work dried up.

Clutching her nine-month-old daughter, she says each day is a decision whether to pay for milk or diapers. “We can’t afford the rent anymore. So we will soon be out in the streets or under a bridge.”

Then she breaks down. “I was hoping for a good life,” she says through tears. “Sometimes I think I should give my children away to social services.”

Brazil is in the grip of a health and social emergency. It has the world’s second-highest death toll from the pandemic at over 370,000, and hospitals are near collapse. A study last week found that 60% of Brazilian households have food insecurity, lacking sufficient access to enough to eat.

President Bolsonaro – who once dismissed the virus as “just a little flu”, opposed lockdowns and failed to secure vaccine supplies in time – has lost support, particularly as the food handouts have declined. Attempts at impeachment are stirring.

But he still has his devoted fans, who insist “the establishment” are trying to destroy him.

Three hours’ drive out of São Paulo, the corn harvest is underway on Frederico D’Avila’s farm. He has 1,300 hectares of the crop, as well as soybean, barley and fava, nestled beside dense pine forests.

And as the harvester cuts through the stalks of corn, he talks of how the president is slashing “the system of kleptocracy – chains of corruption – that have run here for 35 years”.

“President Bolsonaro wants to preserve liberty; he wants people to get out, work, feed their children,” he says. “He wants people to decide if they want the vaccine, not to be obligated by the state. Freedom in Brazil has always been under threat.”

I put it to him that the price of that policy is the public health disaster that Brazil is living through. “It’s not a disaster”, he replies. “We don’t have all the data from other countries so we don’t know true numbers of dead.”

Supporters of the president echo the same line, hammered home by the effective Bolsonaro communication machine with claims that if other institutions, including the Supreme Court, had not tied his hands, he could have managed the pandemic fully.

To the charge that Brazil was desperately slow to order vaccines, they reply that the shots could not have been ordered earlier as they had not yet been approved by Brazil’s health regulator.

When I remind him that many countries ordered large quantities of vaccines pending regulatory approval so they could then be rolled out quickly, Mr D’Avila tells me the Supreme Court could have sued the president if the shots were ordered and then not approved.

“If he had unlimited power like a king, it would be better. He wouldn’t need to deal with the Supreme Court and pressure groups,” he says.

President Bolsonaro is on the back foot. Under fire for mishandling what is becoming a humanitarian crisis and facing a threat from former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, whose conviction for corruption was recently overturned, paving the way to challenge the president in next year’s election.

And all the while hospitals fill up, the food queues grow longer, and this shattered country watches helplessly as fresh graves are dug.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS