By Prof. Samuel Lartey

Ghana’s confrontation with MultiChoice/DStv over subscription pricing, alongside anxieties about Nigerian goods and services “flooding” local markets, has revived a hard question: are we edging into a state-driven, subtle trade war, or running an aggressive consumer-protection experiment inside a free-market economy?

The answer matters because Ghana’s Reset Agenda rests on credibility: keep markets open and competitive, protect households from pricing and tariffs shocks, and still court investment.

Consumer Protection

In Ghana’s evolving digital-market, Minister, Hon. Samuel Nartey George has pursued a consumer-first intervention by compelling DStv/MultiChoice to lower the effective price of pay-TV, securing “more value for the same fee” upgrades that immediately expand channel access and premium content without extra cost, thereby easing household budgets and boosting perceived fairness in a high-inflation environment (now in controversy), while his predecessor, Ursula Owusu-Ekuful, set a structural precedent by designating MTN a Significant Market Player (SMP) and attaching remedial conditions (e.g., tighter pricing conduct, interconnection and on-net/off-net rules, and other pro-competitive obligations) designed to dampen dominance advantages and prevent a single operator from entrenching outsized share; taken together, these moves signal a coherent regulatory arc that uses both immediate consumer relief (DStv value upgrades) and long-run competition remedies (MTN SMP conditions) to shift surplus toward Ghanaian users, stabilize market dynamics, and anchor investment on clearer, rules-based terms.

Trade wars raise prices and inflation, disrupt supply chains, depress business investment and productivity, weaken currencies, shrink consumer choice, invite retaliatory barriers on exports, strain public finances, fuel unemployment and social tension, and ultimately erode international rules while hardening geopolitical blocs and rivalries.

Here’s a clear, Ghana-focused narrative of how a “trade war” would ripple through the economy, society, and geo-politics:

Economy:

A trade war would raise import costs through tariffs and non-tariff barriers, quickly feeding into food, fuel, medicine, and telecom prices; that would intensify inflation, pressure the cedi, and force tighter monetary policy (higher policy rates), increasing borrowing costs for government, banks, and firms.

Import-dependent sectors (energy, refined fuels, machinery, pharmaceuticals, ICT equipment, poultry/fish, packaged foods) would face supply disruptions and FX demand spikes, while exporters could be hit by retaliation, new standards checks, or quotas.

Public finances would strain as debt service rises with weaker currency and higher rates; capital expenditure could be crowded out, slowing infrastructure and jobs. Some protected manufacturers might see short-term relief, but without scale and stable inputs, unit costs rise and competitiveness stalls, deterring FDI and delaying technology transfer.

Stock of unsold goods and working-capital cycles would worsen for SMEs; unemployment and underemployment risks would increase, especially in trade, logistics, hospitality, agri-processing, and media/creative industries tied to regional content flows.

Society:

Households would absorb higher living costs via transport, utilities, and food, eroding real incomes, savings, and school/health budgets; inequality could widen as formal-sector workers and urban middle classes adjust better than informal and rural households. Consumer choice would shrink (especially in medicines, ICT devices, pay-TV/streaming, and specialty foods), while service quality stagnates as firms delay network upgrades and content acquisition.

Rising prices and scarcity can fuel social frustration, industrial action, and petty smuggling; informal cross-border trade may expand, weakening standards compliance and tax collection. Philanthropy, diaspora remittances, and church- or NGO-run safety nets would face greater demand just as donor budgets tighten.

Geo-politics & regional posture

With Nigeria and South Africa as top regional partners and investors, a Ghana-centric trade confrontation invites counter-measures that could limit Ghanaian exports, banking links, media carriage, aviation connectivity, and professional services mobility.

Within ECOWAS and AfCFTA, accusations of non-tariff barriers would consume diplomatic bandwidth, undermining Ghana’s standing as a rules-based hub and host for continental trade institutions; mediation costs rise and coalition-building for security, migration, and health agendas becomes harder.

If European and Asian partners perceive policy unpredictability, they re-price Ghana risk, slow green-energy and industrial-park investments, and shift supply chains to peers with steadier regimes.

Strategically, Ghana would be nudged toward narrower bilateral deals to keep essentials flowing (fuel, pharmaceuticals, fertilizers), trading policy autonomy for short-term relief—diluting its leverage in larger regional initiatives and complicating its “Reset Agenda” that depends on credibility, openness, and stable rules.

Bottom line

A trade war swaps visible, short-term protection for hidden, long-term costs: higher inflation and interest rates, weaker currency and investment, thinner consumer choice, social stress, and a harder diplomatic landscape, outcomes that collectively slow growth, complicate fiscal consolidation, and erode Ghana’s influence in West Africa and under AfCFTA.

The DStv flashpoint: relief today, precedent tomorrow

August 5, 2025:

Government issued an ultimatum to DStv to cut prices by 30% or face license suspension, an unusually hard regulatory lever intended to deliver immediate household relief.

From October 1, 2025:

A negotiated fix, automatic bouquet upgrades that deliver ~33–50% more value at the same price (e.g., Compact, Compact Plus; Compact Plus, Premium). It’s Ghana-only, and it moved the effective price per channel down without cutting the sticker price.

Historically, MultiChoice has run “upgrade-at-the-same-price” promos in Ghana well before Oct 2025, for example, GOtv Ghana’s Step Up ran Jan 5–Mar 31, 2022, DStv Ghana’s Step Up ran Jan 13–Mar 31, 2025, a DStv “We’ve Got You” offer ran Jun 16–Jul 31, 2025, and the latest Oct 1–Dec 31, 2025 edition followed thereafter.

What are these signals:

It is muscular regulation, not a market shutdown. But it tests free-market norms by threatening license sanctions to shape a private price schedule. In a rules-based market, the durable path is transparent competition policy (cost-justification, anti-dominance tests) rather than one-off coercive bargaining.

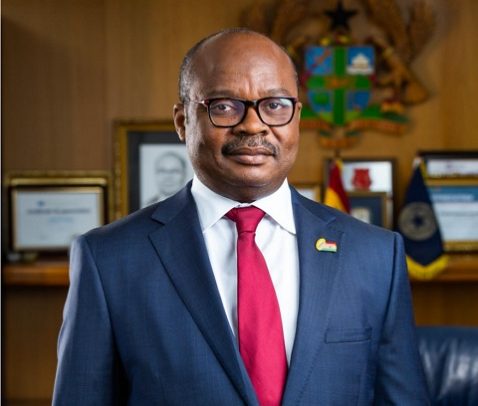

Who sets the tone—and why it matters

The sector’s tone has shifted under Hon. Samuel Nartey George, Minister for Communications, Digital Technology & Innovations (since 2025), whose public stance framed DStv pricing as a consumer-welfare issue. His tenure follows Ursula Owusu-Ekuful (through earlier than 2025). Leadership matters: it cues investors on predictability versus ad-hoc intervention.

Free market vs. “subtle trade war”: what’s the line?

A trade war normally looks like tariffs, quotas, or retaliatory bans. Ghana has not imposed those on South Africa or Nigeria in this episode. Instead, we’re seeing domestic regulatory pressure to obtain consumer concessions from a dominant foreign-owned operator.

That doesn’t breach AfCFTA/ECOWAS rules per se, but heavy-handed tactics can blur into non-tariff barriers if they discriminate or create unpredictable market access. AfCFTA and ECOWAS frameworks explicitly aim to eliminate non-tariff barriers and keep non-discriminatory conditions for goods and services inside the bloc.

The uncomfortable truth: Ghanaian consumers often choose foreign value

Calling Nigerian (or other foreign) offerings an “infiltration” ignores what consumers reveal with their wallets: in many categories, they prefer foreign options, often on price, packaging, and perceived quality.

Poultry as a bellwether:

Studies show Ghana routinely imports a large share of its poultry; imported frozen cuts are cheaper by ~27–30% and fit urban household budgets. In recent years, Ghana ranked among Africa’s top poultry importers, with EU suppliers dominating. Choice is driven by price, convenience, and consistent quality.

Consumer research:

Ghanaian buyers exhibit mixed ethnocentrism, they like local but switch to imports when quality/price/packaging tip the scale. That’s classic consumer sovereignty at work.

Media/services:

MultiChoice’s regional scale (Nigeria, Kenya, SA content pipelines) shapes what Ghanaians watch; the platform effect is a consumer-pulled equilibrium, not just a supplier push.

Implication:

If policy tilts too far toward command-and-control, it risks overriding revealed preferences and can unintentionally raise real prices by shrinking variety or delaying investment.

Nigeria’s spillover: integration, not invasion

Under ECOWAS’ ETLS and AfCFTA, Ghana and Nigeria are meant to trade more, not less. Flows in energy, FMCG, and media reflect regional specialization and scale. Ghana has even explored importing refined fuel from Nigeria’s Dangote Refinery to save FX and cut pump prices, hardly a trade war stance.

How does this square with free-market principles and consumer welfare?

Where it contravenes free-market ideals

Price threats vs. policy rules:

Using license suspension to force price outcomes distorts price signals and raises policy risk premia for investors. Free markets prefer predictable, published rules and ex-post competition enforcement.

Consumer sovereignty at risk:

If government curbs imported or foreign-owned options (directly or indirectly), it can deny consumers the very value, lower effective prices, better packaging, broader content that they consistently select.

NTB optics:

Even without tariffs, unpredictable interventions can look like non-tariff barriers, clashing with AfCFTA/ECOWAS liberalization norms.

Where it aligns with consumer protection

Immediate relief:

The DStv upgrade delivers a material, Ghana-only value gain (33–50% more) at constant cash outlay, a real benefit in a cost-of-living squeeze.

Fair-pricing tests:

A transparent, evidence-based review of cost structures, currency pass-through, and market power is consistent with competition policy—and better than laissez-faire in a thin, concentrated market.

Impacts

Government’s Reset Agenda

- Positive:

Visible consumer wins strengthen the narrative of protecting purchasing power.

- Risk:

If “wins” rely on ad-hoc leverage rather than codified rules, investor confidence in digital, media and telecom could soften, raising the cost of capital and slowing upgrade cycles. Aligning actions with AfCFTA/ECOWAS disciplines helps keep markets open while protecting consumers.

Businesses and corporates

- Expect deeper cost-justification requests and public interest reviews on pricing in consumer-facing sectors.

- Firms with regional scale (content, FMCG, fuel) should anticipate local-value tests in Ghana but plan within AfCFTA rules to avoid NTB disputes.

Households

- Short run:

Effective price per channel on DStv falls, improving access to sports/education content without extra cedis.

- Medium run:

If firms retrench or delay investment due to policy risk, variety and service quality could plateau, which raises long-run consumer costs.

Financial and sustainability angles

External balances:

Re-routing fuel imports to Nigeria’s refinery could save freight/FX and ease pump-price pressure, helpful for household budgets and inflation expectations.

Food security & resilience: Poultry import dependence reflects price-quality gaps. Sustainable relief needs productivity upgrades (feed, cold-chain, certification) so local producers compete on price and safety, meeting the same attributes consumers already seek from imports.

Standards & trust:

Better enforcement of GSA/FDA standards can shift preferences toward Made-in-Ghana without bans, a market-compatible route to resilience.

What a rules-first playbook looks like

Publish a pricing & market-power guideline for digital media/data services (cost pass-through tests, FX sensitivity bands, appeal timelines).

Use competition tools (market inquiries, dominance remedies) before licence threats; reserve coercive powers for clear, rule-based breaches.

Lean on AfCFTA/ECOWAS mechanisms to avoid NTBs while still protecting consumers (e.g., regional codes on bill transparency, bundling, and fair usage).

Back local supply upgrades (quality, packaging, HACCP) so Made-in-Ghana wins on merit where consumers are most price-sensitive (poultry, FMCG).

Conclusion

Ghana is not in a declared trade war. We are running a high-pressure negotiation inside an open-market architecture. The DStv bargain proves government can deliver immediate consumer value, but it also warns that ad-hoc coercion strains free-market norms and AfCFTA/ECOWAS commitments.

Ghanaian consumers do exhibit a strong appetite for foreign goods and services when price, packaging, and quality win so the strategic answer is not to fence off the market. It is to codify fair-pricing rules, upgrade local competitiveness, and keep borders open under clear regional disciplines. That’s how the Reset stays credible, protecting households today while sustaining investment, competition, and real consumer choice tomorrow.

The post Trade war appeared first on The Business & Financial Times.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS