By Gideon SARPONG

Under the relentless blaze of a September sun in 2021, amid the chaotic symphony of cranes and cargo at Ghana’s Tema Port, what began as a mundane customs check unraveled into a spine-tingling exposé of hidden dangers.

Inside a 40-foot shipping container from the United States, falsely declared as personal effects, were nine pistols, eight assault rifles, and 219 rounds of live ammunition.

The discovery first announced by the Ghana Revenue Authority, was not just a smuggling bust but a window into a deeper, more systematic problem: the persistent attempts by criminal networks to arm violent groups in Ghana.

Four years on, the investigation shows that the weapons shipment which were concealed beneath rice and household goods in blue barrels, originated from the Port of Baltimore, Maryland, and was linked to Kojo Owusu Dartey, a U.S. Army Major stationed in North Carolina.

Picture shows one of the barrels where weapons were concealed, source: Ghana Revenue Authority.

According to court indictment documents reviewed as part of this investigation, Kojo Owusu Dartey, orchestrated this scheme with the aid of Staff Sergeant George Archer and others. The indictment noted that these individuals knowingly violated Title 18, United States Code, Sections 922(a)(1)(A) and 924 by engaging in unlicensed firearms dealing and illegally exporting weapons without a license.

U.S. federal authorities later prosecuted Dartey, securing a jury conviction in April 2024 on charges of smuggling firearms without an export license, making false statements to federal agencies, and dealing in firearms without a license. He was sentenced to 70 months in prison in February 2025.

The Ghana Police Service did not respond to a right to information request on possible conspirators in Ghana as part of the September 2021 weapons seizure.

Some of the arms and ammunition shown here after the September 2021 seizure. Picture: DELLA RUSSEL OCLOO

The Attorney General’s office and the Ministry of Interior in Ghana did not respond to a right of reply request and a further request to provide status update on sixteen other cases involving major firearms seizures, diversions and arrests in the last five years in Ghana.

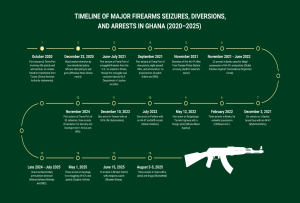

Infographic below:

Cases submitted to the Ghana police, Attorney general, and Ministry of Interior – Timeline

“These weapons were likely destined for groups like violent groups in Bawku, or criminal networks,” says top national security source who spoke to us on condition of anonymity.

That pattern of opacity, and silence by the state has only fuelled a climate of impunity, enabling the very smuggling networks and violent actors the state purports to be combating. “The big people (government officials) themselves are involved in the criminal networks that facilitate arms networks,” said security analyst Professor Kwesi Aning.

Ghana is noted as a supplier of weapons in West Africa to criminal networks. Despite no evidence that the weapons seized at the Tema port was intended for violent extremist groups, several reports have shown how Ghana’s underground artisanal firearm sector end up supporting conflicts internally and within West Africa.

According to a 2020 Small Arms Survey’s report “, Ghanaian gunsmiths are able to produce semi-automatic or automatic weapons, including copies that closely resemble factory-made counterparts such as locally made copies of AK-pattern assault rifles referred to as ‘washman’ capable of single-shot or automatic fire (with a standard 30-round magazine), as well as copies of Russian, Chinese, North Korean, Libyan, and Serbian versions of the world-renowned Soviet AK-47 automatic assault rifles.

Another report by Small Arms Survey titled: Trafficking and smuggling in the Burkina Faso– Côte d’ivoire–Mali region also noted Ghana is a source of black-market explosives and arms trafficked into the tri-border region via routes like Bondoukou–Bouna–Varale–Doropo and through Burkina Faso’s Pô and Zabré entry points. These “ants trade” smuggling operations using motorcycles and concealed cargo supply extremist groups in Mali and Burkina Faso.

In April, 2025, the Ghana police announced it had intercepted 33,000 ammunition packed in 132 boxes concealed in an Accra–Benin bound Hyundai bus during a routine inspection.

This is “very concerning” said the national security official. “The state must thoroughly investigate to identify the powerful people behind this.”

Ghana finds itself at a crossroads: either plug the gaping movement of arms within its own borders or risk becoming the next front in a widening regional war.

In July 2025, Ghana’s late Defence Minister, Omane Boamah, made troubling disclosures about lapses in ammunition control. “I have disclosed that in 2024, there was an incident of ammunition moving from the Ghana Armed Forces to the National Security in 2024. As we speak, the National Security Secretariat under President Mahama is investigating the movement of ammunition,” he stated.

He added: “Beyond that particular case is another one that we have uncovered, that prior to the 2024 incident, there was also theft of ammunition within the Ghana Armed Forces. I am raising this because such ammunitions find their way into the hands of people who are not well trained and have ulterior motives. In a region where armed groups feed off weak institutions and smuggled weapons, the inability to fully prosecute arms trafficking cases is a national security failure of the highest order,” said the national security official.

“Weapons (two cases above) like these don’t just disappear. Someone is arming someone. And we may not want to admit it, but that ‘someone’ could be right across our borders or already within them,” he added.

Failure of the state to aggressively prosecute some previous weapons smuggling cases and related arrests is stark warning of how Ghana, long a beacon of stability in West Africa, can be drawn into the deadly orbit of violent extremist groups.

Jihadist groups and a family’s escape from terror

According to a 2024 report by the Dutch think tank the Clingendael Institute, Ghana’s northern frontier stretching about 500 kilometers along Burkina Faso’s volatile south has become a conduit for supplies, recruits, and safe havens that sustain jihadist insurgencies. The report further notes that the absence of direct attacks on Ghanaian soil appears to be a calculated decision: Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) is avoiding disruptions to these critical supply chains and refraining from provoking Ghana’s relatively capable security forces — at least for now.

Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) is a militant Islamist group operating across the Sahel, linked to al-Qaeda and active in insurgencies in Mali, Burkina Faso, and neighboring countries.

Meanwhile, at the Zini Refugee Camp near Ghana’s northwestern border with Burkina Faso, the effects of this growing crisis are on full display.

In the refugee camp, a dusty outpost in Ghana’s upper west region, Hajiratu, a 32-year-old mother of four, sits under a tarp, her eyes heavy with grief. Years ago, in Fada N’Gourma, Burkina Faso, JNIM militants stormed her home at dusk. “They fired guns, took my husband, blindfolded him with his shirt, and dragged him away,” she recalls, her voice trembling. “Those who resisted were killed on the spot.”

Now among 867 refugees in Zini, a camp established in April 2024, Hajiratu grapples with an uncertain future. Just recently, 46 new arrivals from Kayaa and Pissila in Burkina Faso joined her, fleeing similar ultimatums: “convert to Islam or die,” they said. Asata, another refugee, shares a parallel agony. Her brother was abducted by Fulbe militants, his fate unknown. “I see his terror-filled eyes every night,” she says. “Is he alive, forced to fight, or dead?”

Such personal horrors underscore the impact of Sahel’s jihadist violence into Ghana, where porous borders allow not just militants but also the displaced to cross freely. These accounts, gathered when journalist, Gideon Sarpong visited the camp, reflect the Sahel’s spiralling violence, with over 110,000 displaced to Northern Ghana, Togo, Benin, and Côte d’Ivoire since October 2024, according to UNHCR.

The camp offers fragile safety, but food shortages and education gaps exacerbated by a shift from food aid to cash stipends leave refugees like Hajiratu and Asata dependent on dwindling support, dreaming of farmlands to rebuild their lives.

Some refugees pictured at the Zini Refugee Camp, June 2025, Credit: Gideon Sarpong

Bawku: A Tinderbox at the Border, border challenges & violent extremist groups

Just 30 kilometers from Burkina Faso, the town of Bawku simmers on the edge of collapse. A long-standing ethnic conflict between the Mamprusi and Kusasi communities has escalated into a full-blown armed standoff, transforming this north eastern outpost into one of Ghana’s most volatile frontiers.

CONTEXT: The Mamprusi, descendants of a centralized kingdom tracing roots to the 17th century and known for their warrior traditions, claim historical chieftaincy over Bawku based on providing military aid to local groups against invaders. The Kusasi, who assert indigenous status as the area’s original inhabitants, maintain a traditionally acephalous society led by earth priests (tendaanas) rather than chiefs, and view the Mamprusi as newcomers imposed by colonial British policies favoring centralized structures for indirect rule. At its core, the dispute dating back to the early 20th century and exacerbated by post-independence political meddling revolves around land ownership, chieftaincy rights, and ethnic dominance. This has fueled cycles of violence that have killed hundreds and displaced thousands.

The deeper reality, however, is that insecurity in these areas has reached such heights that even access has become perilous. Journalists working on this investigation were unable to travel to key border communities in Ghana’s Upper East Region due to a recent spike in attacks on commercial vehicles along the Bolgatanga–Bawku–Pulmakom corridor.

The situation has grown so dire that Ghana’s own Inspector General of Police came under fire during a recent visit, with one officer injured in the ambush. In June 2025, President John Mahama publicly called on the military to guarantee safe passage for all passengers regardless of ethnic affiliation and goods along the route, which is a stark admission of how compromised state security has become in parts of the country.

“Now the police are almost not in the major conflict zones in the northern region; it is only the armed forces that are left. That is how serious a trouble we are in,” said Professor Kwesi Aning.

Meanwhile, at the Hamile border post in the Upper West Region, immigration officers, speaking on condition of anonymity, described an unsettling reality: dozens of unmonitored crossing points emerge during the dry season, when, as one officer put it, “every route becomes a potential crossing.” Surveillance systems are broken or non-existent, and officials lack the basic tools to control movement. “Some people just pass through. We can’t track them, we don’t even see them,” one said.

This vulnerability exploded into violence on September 13, 2025, when irate youth, fueled by accusations that an immigration officer aided armed gunmen from Burkina Faso to cross into Ghana and wrongfully attempted to deport a refugee woman, rampaged through the post setting a vehicle ablaze, burning tires, vandalizing the office, and even leading to the tragic collapse and death of a bystander amid the chaos.

Such eruptions not only shatter fragile community trust but underscore the dire urgency of bolstering border security.

Hamile border control, Ghana, June 2025, Credit: Gideon Sarpong

“Ghana has not invested in its borders since 1951 and if you go to any border towns, we have no equipment. Even if we claim there is a security problem, our behaviour and investment do not reflect any insecurity,” Aning added. “It is the quality of training that we give to the border officials, the equipment that are available and a general security strategy that says we see borders as more of zones of engagement and deepening relations and as zones of crime and threat.”

Ghana’s immediate past to Burkina Faso, Boniface Gambila Adagbila, offered a rare public acknowledgment of the threat. “Believe it or not, they [extremists] are able to come into Ghana and go back,” he said in a recent interview. “They move in and go back… They roam, they come to our hospitals and go back.”

This quiet infiltration appears to extend well beyond the borderlands, reaching deep into the country’s urban centers.

“Yes, porous borders can potentially be a problem. Ghana has been a facilitator of violence and criminal networks in West Africa over the last 30 years,” said Professor Aning.

“Terrorists don’t need to come here we go to them because of the criminal networks that are here and because of the level of collusion between state officials and these criminal gangs otherwise ask yourself why should galamsey (illegal small scale mining) be allowed to thrive.”

A 2023 report by Small Arms Survey noted Ghana as a key source of diverted commercial explosives feeding jihadist networks in the Sahel, where “baguette”-style dynamite from its mining sector has been traced to artisanal sites in Burkina Faso and Mali controlled by JNIM.

“Ghana remains the preferred location for the sale of stolen or confiscated firearms,” Gideon Ofosu-Peasah, an analyst with the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GITOC) wrote in a recent article. “JNIM is rumoured to have numerous meeting points and hideouts on the Ghanaian side of the borders with Togo and Burkina Faso.”

The porousness is not incidental, it is structural. A 2023 report by Promediation warns that Ghana’s proximity to Burkina Faso’s Cascades region and northern Côte d’Ivoire has made its northern corridor an attractive fallback zone for armed groups. The report estimates that between 200 and 300 Ghanaian youths have already been recruited into extremist groups linked to JNIM operating in and around the northern borders.

In June 2021, Abu Dujana, a Ghanaian Fulani, carried out a JNIM suicide bombing in Mali, urging attacks in Ghana in a chilling video. Targeting his kinsmen in Karaga, Northern Region, he exploited ethnic tensions and economic desperation.

Democracy and governance analyst R. Maxwell Bone cautions, that unless the militarized approach is replaced with one that prioritizes addressing the social exclusion rendering communities vulnerable to violent extremist recruitment, the security situation will continue to deteriorate.

Way forward

Since 2000, the Bawku conflict has claimed hundreds of lives, displaced at least 2,500 residents, and destroyed over 200 homes, according to a 2024 report published by the Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF). Over 80 people have been killed since 2024 as a result of the conflict.

But the deeper concern lies in how Bawku’s chaos may be drawing the attention and presence of jihadist actors operating in Burkina Faso’s Cascades region. Ghana’s former President, Nana Akufo-Addo, did not mince words in his 2024 State of the Nation Address, calling Bawku a “wasteland of destruction and distrust,” adding, “what should concern all of us and not just the people of Bawku is that, in its current state, Bawku is an alluring magnet to mischief makers and extremists operating a few kilometers across from the border.”

Recent incidents point to the creeping militarization of the Bawku area and expansion into other areas in Ghana. Two male students of Nalerigu Senior High School were shot and killed following a violent attack by unidentified gunmen in July, 2025 believed to be linked to the Bawku conflict.

On the ground, the fear is palpable. “What’s worrying is that you have youth openly brandishing rifles young boys moving with weapons they shouldn’t have,” said Mohammed, a prominent youth leader in Bawku. (His name has been changed to protect his identity.) “Just a few days ago, they stopped a water truck from entering town near the police station. That’s how bold it’s become.”

Mohammed described a town under siege, not just by its own tensions but by a deepening sense of abandonment. “It’s very difficult to get food into Bawku. I need military escort just to travel to Bolgatanga. We are all suffering. We just keep appealing to ourselves to stop, but nothing changes.”

What fuels the conflict, he said, isn’t just old grudges it’s money, ideology, and a steady flow of arms. “The whole conflict has been radicalized. People use all their resources to support it. I know residents from outside Bawku who buy weapons and send them hidden in Land Cruisers. The guns come from cities in the south. And the quantity here is scary. People fire all night and never run out.”

Despite no conclusive record of jihadist groups’ participation in the Bawku conflict, Mohammed’s fears go beyond local dynamics. “With the jihadist situation, I wouldn’t be surprised if some people from Bawku are involved. There’s a perception that both sides have links to jihadists. I doubt it’s widespread, but you can’t rule it out.”

His warning is echoed by Sadik, a fellow youth leader, who insists not just the widespread arming of civilians, but also the role of external funding in sustaining the violence. (His name has been changed to protect his identity.)

The conditions are eerily familiar to Dr. Kaderi Noagah Bukari, a senior research fellow and Head of Department of Peace Studies at the University of Cape Coast who has mapped the evolution of armed civilian groups along Ghana’s northern borders. “Kwelugu, for instance, is home to several armed groups formed mainly by Kusasi communities,” he said. “Originally set up to combat cattle rustling, they now resemble vigilantes very much like the armed self-defense groups operating in Burkina Faso.”

Bukari warned of a widening security vacuum. “There are ungoverned spaces in northern Ghana,” he said. “The absence of sustained state presence has allowed these groups to entrench themselves.”

While Bukari was cautious about drawing direct links between Bawku’s factions and jihadist groups like JNIM or ISIS-Sahel, he was unequivocal about the danger. “The region is heavily weaponised. Most of the arms come from within Ghana, from major cities in the south. And when you combine that level of armament with longstanding grievances and a culture of impunity, it becomes a powder keg. Vulnerabilities like this are exactly what extremists look for.” For Professor Aning, the most threatening contribution to insecurity in Ghana is the “human factor.”

“The inability or incapacity of those mandated by law and the constitution to provide the protection,” he explained. “The sum total of the security challenges facing the country calls into question the effectiveness and the competence of public officials who are dealing with the compounding security challenges. We need a different approach.”

>>>This report was produced as part of the Resilience Fund Fellowship by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime

The post A quiet crisis: Bawku, smuggling, and the extremist war next door appeared first on The Business & Financial Times.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS