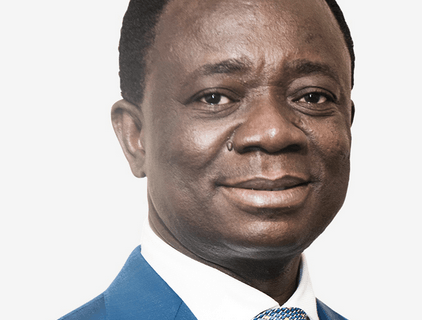

By Divine KPE

For many children in Ghana, the promise of education remains unfulfilled. Despite significant increases in school enrolment over the past decades, more than 1.9 million children of basic school-going age (4–14 years) were out of school as of 2023.

Additionally, many children who are in school are not acquiring foundational literacy and numeracy skills. Evidently, the outcomes of the 2022 National Standardised Test suggest that 48.7 percent and 50.8 percent of Basic Four pupils failed to meet basic competency levels in literacy and numeracy, respectively.

A closer examination of the data by gender, socio-economic status, disability and geography highlights systemic inequalities in access and learning outcomes. As Ghana begins a new chapter under the leadership of its newly appointed Minister for Education – Haruna Iddrisu, addressing these dual crises of inequitable access and poor learning outcomes must be a top priority.

Achieving these largely requires adequate funding to expand school infrastructure, equip schools with teaching and learning resources, and enhance teachers’ capacity, among others. Hence, the case must still be made for the Education Minister to work closely with the Finance Minister to increase funding to education – aiming for the upper thresholds of international benchmarks.

That notwithstanding, studies indicate that simply increasing annual education spending is insufficient; instead, the core of the funding solution lies in prioritising equity and efficiency in resource distribution and utilisation – an area that demands the minister’s focused attention.

Education financing outlook

Ghana’s total education spending has followed an upward trajectory over the past decades, albeit it often falls short of internationally recommended levels of four percent to six percent of GDP and 15 percent to 20 percent of total annual government expenditure.

Over the last decade, education spending more than quadrupled, rising from GH?5.7billion in 2012 to GH?24.3billion in 2022 – a 326.3 percent increase. Relatively, this is positive although adjusting for inflation and analysing per-learner spending highlights gaps that require attention.

The case for equitable spending

Ghana, however, often faces disparities in spending which reveals systemic inequality that disappointedly affects marginalised groups – girls, children form underserved communities and poor households, and children with disabilities. For instance, in terms of socioe-conomic background, Ghana spends three times more (33 percent) on children from wealthiest quintile compared to just 11 percent for children from poorest quintile.

This disparity is reflected in access opportunity where only 52 percent of children from poorest quintile complete primary school, compared to 86 percent of those from wealthiest quintile. Other critical disparity factors like drop-out rates, learning outcomes and participation in educational programmes (e.g., STEM) between specific demographic groups underscore the deficiencies rooted in inequitable spending, like failure to direct education budgets in ways that benefit marginalised groups. For example, inadequate investment in rural school constructions, provision of teaching and learning resources, and adequate teacher supply (like prioritising incentives for rural postings).

Additionally, there is an absence of gender-sensitive budgeting to address gender-specific school challenges, and a lack of disability mainstreamed budgeting approach in education budgeting to support for learners with disabilities in mainstream schools.

It is instructive to know that even without necessarily increasing the percentage of GDP allocation to education, some of the challenges in the sector could be minimised if Ghana allocates resources equitably.

Example, at the current rate of education funding, a one-percentage point increase in the allocation of public education resources to the poorest 20 percent could reduce Ghana’s learning poverty rate by 2.6 to 4.7 percentage points.

The imperative of spending efficiency

A Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) conducted by the author to evaluate the efficiency of Ghana’s basic education system, using key metrics from 2022/2023 academic year, yielded a DEA efficiency score of 79.8 percent.

This indicates that for every unit of input invested (e.g., spending, teacher resources), Ghana achieves only 79.8 percent of the potential output in its basic education system. Assuming basic education funding remains at the 2020 rate (GH?10.3billion), closing the 20.2 percent inefficiency gap could increase literary rate among P4 pupils from the 51 percent to 61.3 percent and numeracy rate from the 45 percent to 54.1 percent.

Net Enrolment Rate could be nearing universal enrolment level (from 75.3 percent to 90.5 percent). The spending inefficiency underscores the critical need for reforms that enhance resource utilisation to maximise educational outcomes, particularly in critical areas like literacy and numeracy.

Underlying causes of spending inefficiency

Spending inefficiencies in Ghana’s education system stem from imbalances in resource allocation, mismanagement, misaligned priorities and systemic accountability challenges. Funding and other inputs are inequitably distributed across educational stages, regions, districts and schools, with underserved communities often facing shortages in infrastructure, learning materials and qualified teachers.

For instance, there is a structural inefficiency in prioritising resources to secondary and tertiary education at the expense of kindergarten education. Successive audits of education sector institutions by the Auditor-General reveal widespread mismanagement of education funds.

Furthermore, limited transparency regarding the use of education funds hinders stakeholders’ ability to monitor and evaluate resource utilisation effectively.

Conclusion and recommendations

The multiplicity of issues within Ghana’s education system requires increased investment. Yet, merely increasing spending without addressing underlying inequity and inefficiency will not necessarily maximise outcomes.

Addressing these systemic issues requires deliberate strategies to ensure every Ghana cedi spent on education directly maximises impact in an equitable manner. Key strategies the minister should pursue include:

- Adopting equity/need-based approaches to resource allocation. By that, gender and inclusive budgeting approaches that address specific challenges faced by girls and learners with disability must be pursued.

- Prioritising efficient teacher deployment, including fulfilling the government’s 2024 manifesto promise to pay teachers who accept rural postings an allowance of 20 percent of their basic salaries.

- Strengthening governance and accountability systems to minimise waste/mismanagement, such as promoting competitive procurement process and undertaking periodic public education expenditure tracking surveys.

- Acting on recommendations in the Auditor-General’s report on audit of ESI.

- Identifying cost-effective interventions/programmes to ensure optimal resource allocation.

- Increasing funding to KG education, where children from the poorest households are more represented, to improve early childhood education outcomes.

About the author

The writer, Divine Kpe, is an Education Specialist.

The post Bridging the gap: The case for equitable and efficient education funding appeared first on The Business & Financial Times.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS