The Government of Ghana (the ‘’Government’’), acting through the Minister for Finance, presented the Mid-Year Fiscal Policy Review of the 2025 Budget Statement and Economic Policy for 2025 financial year (the ‘’Mid-year Budget Statement’’) to the Parliament of Ghana on 24 July 2025 under the theme ‘’Resetting the Economy for the Ghana We Want’’.

The Mid-Year Budget Statement highlighted key macroeconomic and sectoral performances of the economy for the first half of the 2025 financial year. Key among the topics presented were updates on inflation and price stability, interest rate developments, debt restructuring and sinking fund strategies. Key reforms and initiatives planned by the Government included Value Added Tax (VAT) reforms and the 24-hour economy.

This article discusses the current VAT scheme in Ghana and assesses the future implications of the proposed reforms at both the micro and macro levels of the Ghanaian economy.

Brief introduction to VAT and its significance in Ghana’s Economy

The first VAT law passed by the Parliament of Ghana was the Value Added Tax Act, 1994, Act 486, which was scheduled to come into effect in 1995. However, the passage of the Act was met with fierce resistance from the general public, leading to a bloody demonstration in the national capital in which several people lost their lives.

[i] In 1998, due to strong political management of this tax type, sufficient lead time between the proposed Act and its implementation, among others, the Value Added Tax Act, 1998, Act 546 was successfully enacted. In December 2013, the Value Added Tax Act, 2013, Act 870 was passed to revise and consolidate the law relating to the imposition of VAT and to provide for related matters.

Ghana functions as a unitary republic state,[ii] meaning that the government is responsible for enacting its policies and collecting tax revenues across the country. The revenue sources are diverse but can generally be categorized into two main types: tax revenues and non-tax revenues. In 2024, non-tax revenues, excluding grants, amounted to GHS 27.7 billion, which was approximately 2.4% of the country’s GDP. Majority of these funds were generated from retention, fees and charges, dividend and surface rentals from oil interests.

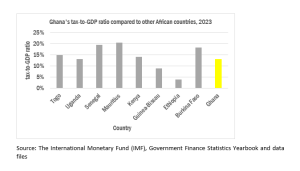

In that same year, total tax revenue collection amounted to GHS 151.1 billion, representing a tax-to-GDP ratio of 12.9%.[iii] This percentage is less than the average rate in some comparator countries in the region and in countries with similar revenue levels.

The unweighted average tax-to-GDP ratio (total tax revenues including social security contributions as a percentage of GDP) for 36 countries in OECD’s report was 16.0% in 2022.[iv] While some African countries such as Mauritius and Senegal recorded tax-to-GDP ratios of 20.5% and 19.5% respectively, Ethiopia and Guinea-Bissau were among the least performing countries, with ratios of 3.9% and 8.8% respectively.[v]

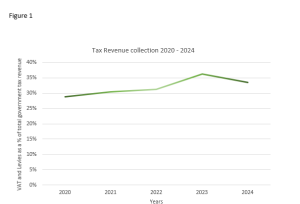

With specific reference to Ghana, VAT and its associated levies have contributed approximately one-third of the Government’s tax revenue over the past five years (Figure 1).

Note: Total tax revenue excludes social contributions, non-tax revenue and grants.

Source: Ministry of Finance

Key VAT policy reforms and the Current VAT Model in Ghana

VAT in Ghana has undergone a plethora of reforms since the enactment of Act 546. Kindly refer to the schedule below for some significant changes in VAT between 1999 and 2025.

Table 1

| Year | Key Reforms | Amendment Act |

| 2000 | Standard VAT rate increased from 10% to 12.5% | Value Added Tax (Amendment) Act, 2000, Act 579 |

| 2001 | VAT registration threshold reduced from GHS 20,000 to GHS 10,000 | Value Added Tax (Amendment) Act, 2001, Act 595 |

| 2007 | Introduction of VAT Flat Rate Scheme (VFRS) for retailers of goods at 3% | Value Added Tax (Amendment) Act, 2007, Act 734 |

| 2013 | Vat registration threshold increased to GHS120,000 with standard rate of 15%.

VFRS abolished |

Value Added Tax, 2013, Act 870 |

| 2015 | Standard rate VAT registration threshold increased to GHS 200,000 | Value Added Tax (Amendment) (No.2) Act, 2015, Act 904 |

| 2017 | VFRS reintroduced for retailers and wholesalers of goods at 3%

Introduction of VAT withholding |

Value Added Tax (Amendment) Act, 2017, Act 948

Value Added Tax (Amendment)(No.2) Act, 2017, Act 954 |

| 2018 | Decoupling of GETFund Levy and NHI Levy

Standard rate of 12.5% reintroduced |

Value Added Tax (Amendment) Act, 2018, Act 970 |

| 2021 | Introduction of Covid-19 Health Recovery Levy – applicable to both VFRS and Standard rate.

VFRS amended to cover only retailers who made annual turnover between GHS 200,000-GHS 500,000 only |

Covid-19 Health Recovery Levy Act, 2021, Act 1068

Value Added Tax (Amendment) Act, 2021, Act 1072 |

| 2022 | Standard VAT rate increased from 12.5% to 15% | Value Added Tax (Amendment)(No.2) Act, 2022, Act 1087 |

| 2023 | Introduction of VFRS on commercial property rental and immovable property by an estate developer at rate of 5% | Value Added Tax (Amendment) Act, 2023, Act 1107 |

From the table above, it is noticeable that over the last twenty years, the major VAT reforms have covered adjustments to the standard rate, the VAT registration threshold and the introduction/abolishment of the VFRS, among others.

Overview of the current VAT Model: Focus on Standard Rate and Flat Rate suppliers

VAT is imposed on the supply of goods and services made in Ghana, excluding exempt goods or services, and on the import of goods or services other than exempt import.[vi] A taxable person who makes taxable supplies of GHS 200,000 within a year or a proportionate part thereof within a quarterly or monthly period is required to register for VAT. Despite the threshold provided above, promoters of public entertainment, auctioneers or national, regional, local or other authorities or bodies that carry on any taxable activity are required to apply for registration.

Although there are various forms of supplies, this article will focus on standard rate and flat rate suppliers.

Standard Rate Suppliers

Standard rate suppliers include service providers and wholesalers who meet the registration threshold discussed above. They also include retailers of goods who make annual taxable supplies in excess of GHS 500,000. Given that Ghana operates the invoice-credit system, a taxable person under the Standard Rate regime can deduct VAT paid from the VAT collected from customers/consumers, with the net amount remitted to the Ghana Revenue Authority (GRA). This means that service providers and wholesalers as well as retailers who qualify can pass on the VAT incurred on their purchases until it reaches the final consumer of the product who ultimately pays all the VAT (incidence of tax).

Flat Rate Suppliers

Retailers of goods with an annual turnover between GHS 200,000 and GHS 500,000 fall under the VFRS. Unlike under the standard rate scheme, retailers who fall under the VFRS are not allowed to deduct input VAT from the output VAT. Instead, the VAT incurred by such retailers is absorbed as part of their business costs. They are required to charge VAT at a rate of 3%.

The second category of suppliers under the VFRS includes taxable persons who make taxable supplies of immovable properties for rental purposes and the supply of immovable property by estate developers. They are required to charge VAT at a rate of 5%.[vii]

Overview of the Proposed Reforms

- Abolishment of the Covid-19 Health Recovery Levy (COVID-19 Levy): Covid-19 levy of 1% is imposed on the value of taxable supplies of goods or services or the value of the imports.[viii] This rate also applies to persons under the VFRS.[ix] In 2024, the Government reported GHS 2.7 billion in revenue from the Covid-19 levy, which accounted for approximately 1.81% of the government’s tax revenue. It is worth noting that this levy has contributed approximately 2% of the total government revenue over the past five years. With this removal, it is generally anticipated that the Government will seek other revenue sources, such as oil and mineral royalties, to compensate for the potential loss of this revenue inflow.

- Removal of the cascading effect of the National Health Insurance Levy (NHIL) and Ghana Education Trust Fund (GETFund) Levy (the ‘’Levies’’): Currently, there is a 6% of the product sale price (NHIL – 2.5%, GETFund Levy – 2.5%, Covid-19 Levy -1%) applicable in determining the taxable value for VAT purposes. Theses levies are not VAT deductible, meaning that suppliers bear this cost which may be absorbed by them or wholly/partially passed on by them to the final consumer. NHIL and GETFund Levy contribute approximately 9% of the government’s tax revenue. Although the Government plans to remove the cascading effect of these levies, it is expected that, as previously existed before the decoupling of the Levies, a percentage of the composite VAT rate will be earmarked for the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) and GETFund as mandated by existing laws.[x]

- Increment of VAT registration threshold: The Government’s plan to increase the VAT registration threshold in order to exempt small and micro businesses is welcome news for such enterprises. They will be relieved from the administrative challenges of the current system. Also, by excluding these businesses from the VAT bracket, they will no longer be subject to penalties associated with VAT compliance, such as failing to issue a tax invoice. This infraction attracts a penalty of up to GHS 50k or three times the amount of tax involved, whichever is higher. This penalty may be imposed in addition to a fine of not more than GHS 1.2k or to a term of imprisonment not exceeding six months or both.

- Removal of VFRS: The Government intends to eliminate the VFRS. As discussed under ‘’ Overview of the current VAT Model’’, the scheme currently applies to two categories of supplies. The elimination of the VFRS and the implementation of a unified rate will enable the affected businesses claim input VAT paid on their inputs/purchases, thus, eliminating the cascading effect (tax-on-tax) they experience with the current system.

- Reduction of effective VAT rate: Since the enactment of Act 870, there has been a linear increase in the effective VAT rate: from 17.5% (January 2014 to July 2018), to 18.125% (August 2018 to March 2021), to 19.25% (April 2021 to December 2022), and 21.9% (January 2023 to date). The current effective VAT rate is influenced by the application of the three levies to the original sales value in determining the taxable value on which the VAT rate of 15% is applied. Ghana’s effective VAT rate of 21.9% appears to be on the high side when compared to the VAT rates of other sub-Saharan African countries, such as Nigeria (7.5%), Cote d’Ivoire (17%), The Gambia (15%), South Africa (15%) and Liberia (10%).

Impact on Businesses and Consumers

The VAT reforms by the Government are expected to have significant implications for businesses. The abolishment of the Covid-19 Levy and the removal of the cascading effect of levies will reduce production costs for businesses. This change could enhance cash flow for companies, allowing them to reinvest in their operations, expand their services, and lower prices for consumers. Additionally, increasing the VAT registration threshold to exempt small and micro businesses from VAT obligations will relieve these smaller entities of compliance costs and administrative burdens, fostering a more conducive environment for entrepreneurship and growth in the informal sector. Furthermore, with these proposals, it is expected that businesses will be relieved of the Court’s recent decision in Scancom PLC v The Commissioner-General[xi], where it was held that NHIL and GETFund Levy were applicable on imported services, irrespective of whether these imported services were used to produce taxable or exempt supplies.

For consumers, the anticipated reduction of the effective VAT rate from 21.9% may lead to an increase in the purchasing power of households, allowing consumers to allocate more funds toward savings or other expenditures. However, the impact on consumers will also depend on how businesses respond to these reforms. If businesses pass on the savings from reduced taxes to consumers, it will enhance overall consumer spending and stimulate economic activity. Conversely, if businesses choose to maintain their prices, the anticipated benefits of the VAT reforms will not fully materialise for consumers.

Impact on Government’s Revenue

The reforms may initially seem to threaten government revenue. However, these reforms can positively impact tax revenue in several ways. By simplifying the tax structure and reducing the burden on small businesses, the reforms can encourage compliance and broaden the tax base. The removal of the cascading levies will enhance transparency and fairness in the tax system, fostering a more conducive environment for business growth. Furthermore, a lower VAT rate can stimulate consumer spending, boosting economic activity and generating additional tax income for the government.

These reforms are urgently needed, especially at a time when Ghana’s tax-GDP ratio has been hovering between 12.3% and 14% in the last five years. At 12.9% in 2024, Ghana’s tax-to-GDP ratio remains below the average tax-to-GDP ratio (16%) for Sub-Saharan Africa.[xii] These reforms are anticipated to result in an increase in the ratio in the short- to medium-term, thereby promoting sustainable growth across various sectors of the economy.”

Figure 2

Source: The International Monetary Fund (IMF), Government Finance Statistics Yearbook and data files

Conclusion

The Minister for Finance indicated that the Bill for these reforms is expected to be introduced by October and subsequently passed into law, effective January 2026. Although we await specific details of the amendments, there is every indication that the reforms will be welcomed by the business community. This is because, while these proposals aim to address challenges within the current VAT regime, they are likely to stimulate economic growth by creating an enabling environment for businesses. Consequently, the Government should ensure extensive stakeholder engagement to secure the necessary support and commitment prior to implementation. Additionally, it is necessary for the government to commence an intensive public education and sensitisation campaign by collaborating with other state agencies, including the National Commission for Civic Education (NCCE).[xiii] Lastly, considering the low outlook of the country’s tax-to-GDP ratio over the past years, I recommend that the government focus on broadening the tax base to include the informal sector, which presents a substantial opportunity for untapped revenue. To accomplish this goal, I believe that leveraging technology and implementing reforms to streamline compliance processes will be essential.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal or professional advice.

The views reflected in this article are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the global EY organisation or its member firms.

Derick Kwasi Boamah is the author of this article. Derick is a Manager, Global Compliance & Reporting, with Ernst & Young Chartered Accountants. He may be contacted at [email protected]. The article was reviewed by Kofi A. Akuoko (Associate Director) and Isaac Nketiah Sarpong (Partner) of Ernst & Young Chartered Accountants. Kofi and Isaac may be contacted at [email protected] and [email protected] respectively.

[i] Word Bank, ‘’Introducing a value added tax: lessons from Ghana’’, in Prime Notes Public Sector Number 61,2001.

[ii] Article 4(1) of the Constitution of the Republic of Ghana

[iii] Appendix 2B of the Budget Statement and Economic Policy of the Government of Ghana for the 2025 financial year

[iv] OECD, ATAF and AUC, 2024. Revenue Statistics in Africa 2024. OECD Publishing. The OECD’s publication ‘Revenue Statistics in Africa’ reflects a two-year gap between the year of publication and the year of analysis. The most recent edition, published in December 2024, utilises data from the year 2022.

[v] Government Finance Statistics Yearbook and data files, International Monetary Fund (IMF)

[vi] Section 1(1) of Act 870 (as amended)

[vii] Section 3 of Act 870 (as amended)

[viii] Section 1(4) of Act 1068

[ix] Section 1(3) of Act 1068

[x] Ghana Education Trust Fund Act, 2000, Act 581 (as amended) (the ‘’GETFund Act’’); and National Health Insurance Act, 2012, Act 852 (as amended) (the ‘’NHIA Act’’)

[xi] Suit No. CM/Tax/0008/22

[xii] OECD, ATAF and AUC, 2024. Revenue Statistics in Africa 2024. OECD Publishing – Ghana

[xiii] Article 233(d) of the Constitution of the Republic of Ghana

The post Value Added Tax in Ghana: Current model and future implications of proposed reforms appeared first on The Business & Financial Times.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS