By Maria OGBUGO

The global shipping industry under the umbrella of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) has committed to cutting emissions from shipping to net zero by or around 2050.

The 2023 IMO Revised Strategy hinges on the combination of a goal-based greenhouse gas (GHG) fuel intensity standard and a maritime GHG emissions pricing mechanism to achieve the goal.

The IMO’s Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC), the body which is responsible for designing and agreeing on mid-term greenhouse gas reduction measures, has been working within this framework to encourage the IMO’s one hundred and seventy-six member states to reach a consensus on the exact form and design of the mid-term measures to achieve net zero emissions.

By the end of the last meeting of the MEPC in October 2024, four leading proposals had emerged with notable differences between them. In January 2025, it was announced that a paper titled “Consolidation of the proposals for an economic element of the mid-term measures based on a GHG levy/contribution” had been submitted to the MEPC by a group numbering about fifty states.

The paper was a consolidation of the three proposals put forward by the European bloc, the Pacific bloc and the International Chamber of Shipping group. The fifty co-sponsoring states hailed the consolidated paper as a breakthrough for the levy proponents and which they say put them in a majority in the event of a vote.

He who feels it, knows it

The consolidated paper however has only three African countries, Nigeria, Kenya and Liberia, as part of its co-sponsors. Save for Angola and South Africa who aligned with a no-levy proposal by Angola et. al, the remaining forty or so African states have not declared support for any proposal.

It is unsurprising that African states would be wary about the levy. Many studies, including comprehensive impact assessments carried out by UNCTAD, have forecast that Africa, which comprises developing states including a majority of the world’s least developed countries (LDCs), will be most disproportionately negatively impacted by a levy, with the resulting increase in freight rates likely to exacerbate existing imbalances in freight and worsen an already critical situation of food insecurity on the continent.

During the recently concluded expert working group on food security, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations demonstrated that a 10% increase in maritime transport costs leads to a 3.4% increase in the food import bills of developing countries.

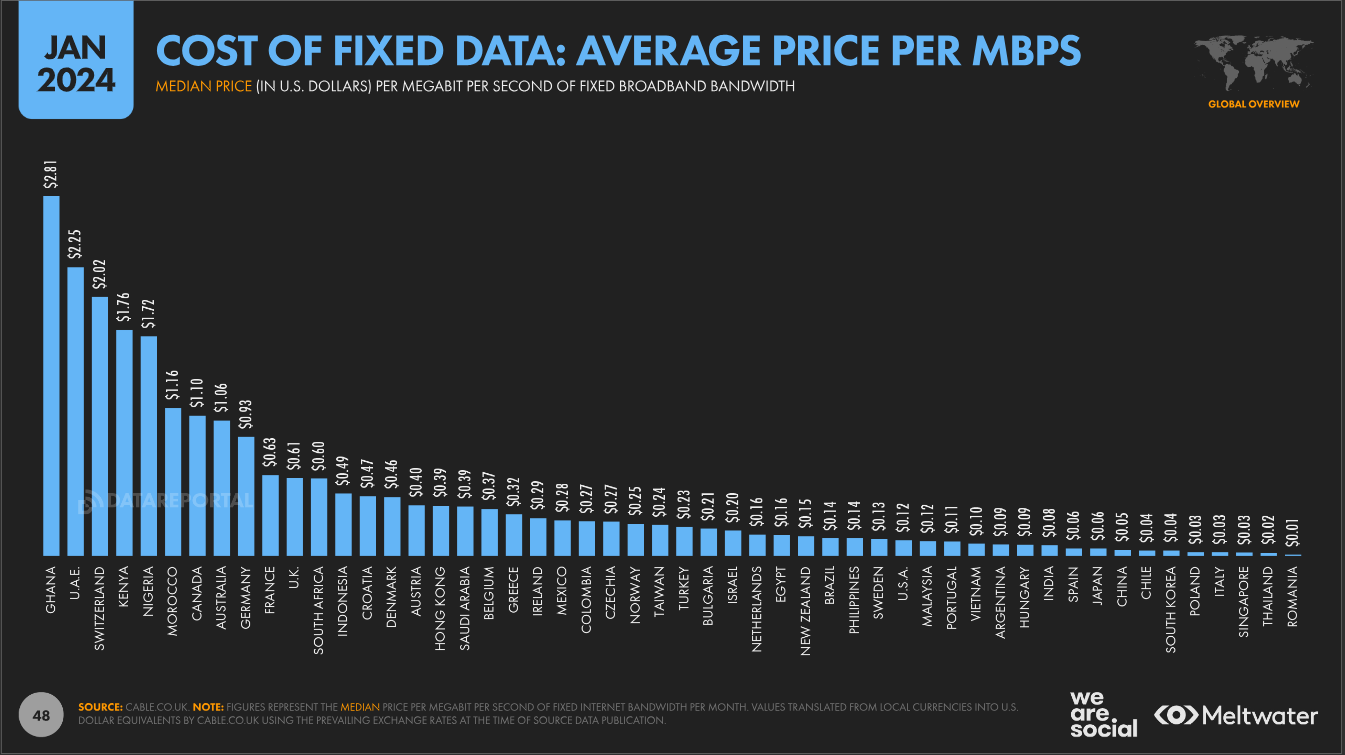

Ghana’s food import bill for 2022 was reported to be USD2.6 billion meaning that should the levy introduce a shock of 10% to maritime transport costs, this will increase our food import bill by some USD91million within 12 months of implementation, with more than half of the changes in the food import bill occurring within the first six months from the shocks. That is USD91million additional expense for a high debt distressed African economy to find in hard currency just to maintain the same level of food availability, on top of its myriad problems.

Africa does not need to imagine what the impact of the proposed levy will be on our economies because, thanks to the European Union (EU)’s climate policy, we already know what this feels like. Since January 2024, the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS) has been extended to cover emissions from shipping.

This meant that ships are required to pay a levy to the EU for polluting. Beginning January 1, 2025, 70% of the emissions generated on sailings between Africa and European ports are to be levied. In addition, a new regulation, FuelEU Maritime, has been introduced by the EU, setting a limit on the average greenhouse gas intensity of fuels used by a ship that calls on European ports, irrespective of its flag.

In response to these regulations, international shipping lines have imposed what they call emissions surcharges to recover these costs from cargo interests, and in the case of many African countries, these charges are payable at destination by the importer. For Ghana, the combination of these two regulations has resulted in an additional USD147 per 20ft container imported from Europe.

Not only has this caused an approximate 10% increase in maritime transports costs in the past 12 months alone, the surcharge on the routes to Ghana are 10 times higher than for sailings from Europe to other regions, e.g. Canada. As if this were not bad enough, studies have also shown that some shipping lines are pegging the surcharges at levels that far exceed cost recovery thereby generating windfall profits; essentially profiting from polluting.

Worse still, the shipping lines get to keep all the cash collected from importers as interest-free cash float for an unbelievable eighteen months, before they are required to pay the levy to the European Commission’s Innovation Fund where it is used to fund the greening of the European shipping industry only.

Agree to disagree

Having established that a levy would have disproportionate negative impacts on African economies, one would have hoped that the recent consolidated levy position would provide comfort on how to address these.

The levy paper can hardly be described as consensus; in fact, the most significant agreement reached therein is that the economic measure should take the form of a flat rate levy. On the other key issues of what the size of the levy should be, whether the fund will be used to fund only projects within the boundaries of international shipping and on how the fund will be managed, the co-sponsors have yet to find common ground.

And for the African policymaker who is in search of ways to mitigate disproportionate negative impacts of the levy, the consolidated paper doesn’t contain clear language showing that the revenues raised will in fact translate into non-interest-bearing capital for African states to fund their energy transition. And then there is the skew in favour of small island developing states (SIDS) and LDCs over other countries, even those with similar climate vulnerabilities.

While Africa may be home to about 70% of the world’s LDCs, there are countries in Africa that are not LDCs, but which have similar if not higher climate vulnerability than some SIDS. For example, according to The Scale, Ghana and Fiji are equal on the climate vulnerability index and yet, according to the consolidated paper, SIDS could potentially have a guaranteed seat on the board of the fund and be prioritized in the distribution of revenue, while Ghana as a coastal, middle-income country with high climate vulnerability and high public debt distress will have to compete with other developing countries for fund revenues.

African giants

So then, what are the motivations for Nigeria, Kenya and Liberia in co-sponsoring the levy proposal in its current form? In the case of Liberia, it is no surprise that it aligns with the International Chamber of Shipping’s position seeing as Liberia is currently the largest open flag registry in the world. Question is whether Liberia as an LDC which exhibits a high reliance on imports of staple foods and which is marked by increased vulnerability to market shocks and global food-price volatility has convinced itself that its economy will be sufficiently protected if the levy lands at say USD100 per ton of carbon?

Similarly, it would be insightful to learn from Nigeria whether perhaps it has found comfort that its national fleet which stands at 33rd place in the global ranking, will be aided by levy revenues to transition to green fuels and technologies in the near term? Or perhaps the levy proposal contains text that assures Kenya of billions in interest-free capital to deploy its ambitious vision to be a major producer of green hydrogen as a shipping fuel?

Divided we fall

And that brings me to the subject of African (dis)unity and the lack of a consolidated or co-ordinated response to what could clearly have a significant impact on the continent. While the European Union member states have demonstrated utmost solidarity in the Austria et. al. proposal, there is no coalescing around a common African position in this all-important negotiation.

The entire process has been marked by lack of leadership. The group of African negotiators at the IMO, African Maritime Advisory Group (AMAG), has made some ad hoc and feeble attempts to coordinate an African response; an occasional meeting or two at the sidelines of the main MEPC sessions; which have been unsuccessful in delivering a thorough, well-articulated African response as they have lacked direction and structure.

On a regional level, Africa’s maritime bodies such as Association of African Maritime Administrators (AAMA), Maritime Organisation of West and Central Africa (MOWCA) and Maritime Organisation of East, South and North Africa (MOESNA) have not been able to convene their respective member states to share their thoughts on the various proposals before them. Finally, at a continental level, both the African Union Commission and the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) Secretariat appear to be completely missing in this critical conversation that will undoubtedly impact how Africa trades amongst itself and with other regions of the world.

In unity lies strength, and this principle was manifest at the MEPC82 in October 2024 when Egypt and Togo led the call, supported by other African states, for the IMO to conduct further work on the impact of the measures on food security. But before the report on this further work could be issued, Nigeria and Kenya break rank and declare support for a position without carrying along other states. While the author recognises sovereignty of African states, the continent’s bargaining position is severely weakened if all its states are not joined as one voice to together seek the outcome that is best for Africa as a collective.

Game theory – stag hunt

There is an urgent need to coordinate an African position and to amplify Africa member states’ collective voice during the negotiations. Lessons and experiences can be drawn from the African Group of Negotiators (AGN) who have over the years, in unison, achieved increased African visibility, voice, and forged common positions within the UNFCCC climate negotiations. The Africa group at the IMO could most certainly benefit from similar levels of coordination to raise Africa’s influence in these negotiations.

This will however require funding of in-person strategy meetings by African member states, facilitated by subject-matter experts, at which they can have detailed discussions about the various proposals and how their various economies stand to be impacted. Having gained thorough understanding of the various options, they can together reach an informed position and be able to strengthen African bargaining power at the IMO. This coordination will facilitate and enhance effective Afrocentric engagement in the international and national climate change policy formulation, implementation and decision making.

Zone of possible agreement

Clearly, there is still some way to go on the levy proposal for it to be attractive to the rest of Africa, and with the clock fast ticking towards MEPC83 in April 2025, African states must be clear in their minds what they want. Research has shown that the priorities are that food security is not further worsened, that the disproportionate negative impacts are mitigated, that revenues from the levy are distributed equitably in line with climate, social and economic vulnerability and that the funds are redistributed as non-interest-bearing capital to fund Africa’s transition without limiting the uses of funds to shipping’s value chain only. If these key elements are unattainable from the levy proposal, Africa should not be blamed for viewing the competing no-levy proposals as a better alternative. And no-levy does not equate no climate action; it only means a slower, more cautious pathway.

Showing up is half the battle

Attending the IMO meetings this spring is a must for all African IMO member states, and I call on all African governments and funders to prioritise this in their budgets. For African states to be effective in this all-important meeting, their delegations should ideally comprise of technical advisors for the discussions on the fuel standard, economists and public finance experts for the discussions on revenue distributions, diplomats for negotiating and bridging consensus with the sponsors of the various proposals, lawyers for drafting the text, and finally researchers to provide the delegation with on-the-go information to aid decision-making.

The practice of African governments sending one or two technical persons to London to attend these meetings has meant that African delegations are often limited in their ability to achieve effective, wide-ranging results. And while the cost of a multi-disciplinary five- or six-person delegation may appear expensive, doing it any other way will be exponentially more expensive in the long run.

Constituting these delegations too is a matter of strategy. Member states should bear in mind that the IMO is a place of intense politics and hence the delegates they send should not only be experts in their fields but must also be familiar with the landscape and have a high level of emotional intelligence. The practice of sending a new different delegate to each IMO meeting does not augur well for the negotiation process.

Call to action

Climate action is urgent and necessary, but it must be equitable. While the levy is a sure way to achieve the Revised GHG Strategy, it is important that the text is negotiated to address Africa’s concerns. For African states to influence the discussions, they need to approach the negotiations as a collective.

This requires support and funding to convene African stakeholders to hold urgent dedicated strategy sessions outside the IMO. Funders, NGOs and other interested parties should lend their support to organisations that are working to increase co-ordination at the continental level. It is my hope that having built capacity of member states to build a well-thought-out position, African states will show up and participate collectively and effectively towards negotiating an outcome which not only sets shipping on the right course to achieve the Revised GHG Strategy but is also just and equitable for the continent.

Maria is a Maritime Consultant. She consults for Ahorlu Marine Limited, African Future Policies Hub, Climate Champions Team and the International Maritime Organization on shipping’s decarbonization and how it can support the development of the maritime sector in Africa.

The post Decarbonising shipping: Where does Africa stand? appeared first on The Business & Financial Times.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS