Kenyan literary giant Ngugi wa Thiong'o, one of Africa's most influential writers and a fierce advocate for linguistic decolonization, died on Wednesday, May 28, 2025, at the age of 87.

His death marks the end of an era for African literature, but his revolutionary ideas about language, identity, and resistance continue to inspire writers across the continent.

For most of his career, Ngugi wa Thiong'o was known not just for what he wrote, but for what language he refused to write in.

In a move that shocked the literary world, he abandoned English to writing only in his native Kikuyu language.

Well, imagine reading this article in Ewe, Twi, Ga or any other famous Ghanaians dialect. This is the incredible story of Ng?g? wa Thiong'o.

The Great Language Revolution

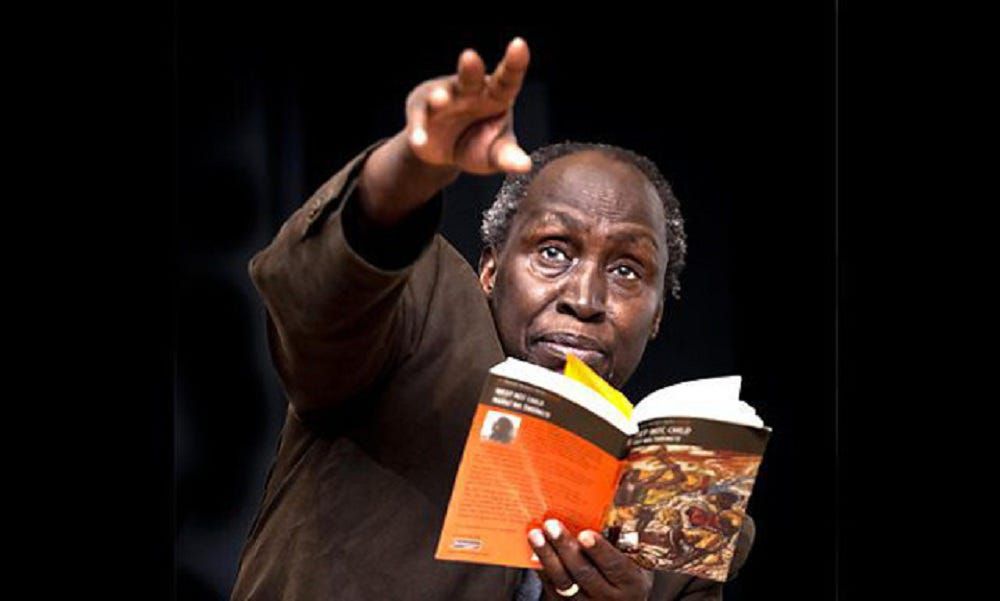

Born James Ngugi in 1938 in colonial Kenya, he initially wrote in English and achieved early success with novels like the famous Weep Not, Child in 1964 and The River Between in 1965. These works explored Kenyan culture and the clash between traditional and colonial values, establishing him as one of Africa's most promising voices.

ALSO READ: Africa’s golden emperor: How Mansa Musa became the richest man in history

But by 1970, everything changed. He dropped his English name James Ngugi, became Ng?g? wa Thiong'o, and made a radical decision: he would write only in his native Gikuyu language. This wasn't just a personal choice, it was a remarkable political revolution.

His masterpiece A Grain of Wheat in 1967 had already shown his growing political consciousness, but his complete break with English sent shockwaves through the literary world.

How could Africa's celebrated writer abandon the language that made him internationally famous?

The Price of Principles

Ngugi's answer came in his most influential work: Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature in 1986. In this groundbreaking collection of essays, he argued that language carries culture, values, and worldview.

When African writers chose European languages, he contended, they perpetuated colonial mental slavery.

He wrote.

The language of African literature cannot be discussed meaningfully outside the context of those social forces which have made it possible.

For Ngugi, writing in English meant thinking with a colonized mind.

This commitment cost him dearly. His political activism and critical writings about post-independence Kenya led to his imprisonment without trial in 1977.

During his year in detention, he wrote his first novel in Kikuyu on prison toilet paper, marking powerful symbol of resistance.

After his release, continued government harassment forced him into exile, where he spent decades teaching in American universities while advocating for African languages.

Transforming a Continent's Voice

Ngugi's language revolution didn't just change his own writing, but also transformed how an entire continent thought about literature.

His decision inspired countless African writers to embrace their mother tongues, from Yoruba poets in Nigeria to Shona storytellers in Zimbabwe.

He proved that African languages weren't just suitable for literature, they were essential for authentic African expression.

His novels in Kikuyu, when translated, demonstrated that stories rooted in African linguistic traditions could speak to universal human experiences while maintaining their cultural authenticity.

A Living Legacy

Every person, whether in Africa or Europe, has a right to their mother tongue, Ngugi declared. This simple statement became a rallying cry for linguistic diversity worldwide.

At his death, Ngugi was Distinguished Professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of California, Irvine—an irony he often noted with humor. Though he taught English literature, his heart remained with the languages of his homeland.

His influence extends far beyond books. Today's African filmmakers, musicians, and content creators continue grappling with his central questions:

In what language should we tell our stories? Who decides which languages have value? How do we honor heritage while participating in a globalized world?

The Lasting Impact

Ngugi lived to see validation of his linguistic prophecy. African languages increasingly appear in international literature, film, and digital media.

His vision of a decolonized African mind—one that thinks and creates in its own languages—is despite slowly becoming reality even in African music.

Young Africans across the continent now write poetry in local languages, create content in mother tongues, and tell stories that would have been considered unmarketable in Ngugi's early career.

From Ghanaian musicians rapping in Twi to Nigerian filmmakers using Igbo, his revolution continues.

ALSO READ: From talking drums to trending tweets: How Africa found its digital voice

His death closes the book on literature's most principled rebel, but for countless writers who now create in their native languages, Ngugi's revolution lives on.

He proved that the most powerful act of resistance isn't picking up a weapon, but also choosing which language to speak when you tell your truth.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS