Fighters in the Dambe tradition live very extreme lives. They will do almost anything for the glory of victory.

The dull hum of a large crowd, punctuated by the occasional scream and urgent applause is the first thing that you hear.

Behind the gates where an attendant charges a small fee, men, women, and children surround a large open field. Some stand. Others sit on wooden benches lifted on platforms to give the brief illusion of an arena, but you find people about anywhere else.

Sachets of water, cheap alcohol and a few bottles of cola and orange drink release respite from the dry air. As you shuffle to find your place in all this, your eyes glance over cigarette butts, roaches and empty bottles of codeine. Some in the crowd are only there in body.

In front, there is a stage where a couple of older men sit; musicians call out a drum-driven fight song. The announcer, himself is also a good singer.

For all the pomp on display, what everyone has come to see is something far less glorious.

In the center of the arena, a young man wraps a dirty cord tightly around his arm, glancing around like he's counting the hours till he gets into trouble. His enemy is doing the same.

As soon as the fight begins, the two fighters set on each other, waving their wrapped arms in a bid to do damage. With time, one lands the first blow across the other’s forehead, spilling warm blood to loud Hausa music.

They keep at it, blow for blow until 10 minutes later, the latter twitches to the ground. The fight has come to an end.

This traditional wrestling is "Dambe", practiced by the Hausa people of Northern Nigeria, Chad, and Niger. Dambe was unique to the Butcher castes who used it as sport and entertainment.

Later, they staged fights to entertain visitors during market days in large towns. With time, it became a major tradition across Arewa-land. Later, it was adopted by the local military as a way of getting warriors and recruits ready for war.

Nowadays, fighters travel around the country, jousting at competitions and festivals.

ALSO READ: Before Playstation and X-box, we had Suwe, Ten-Ten and Table Soccer

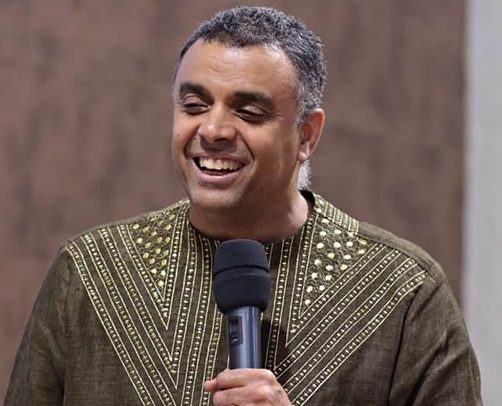

The 24-year old who has won the fight we just saw is one of those who does a lot of travelling. Since he began to fight in 2002, he has won the National Championships twice, as well as competitions in places like Argungu and Lagos.

His name is Sharif Gani.

In the time he has spent training and fighting to get to the pinnacle of the sport, Dambe has taken a toll on Sharif.

The slight shade of youth that flashes across his face is covered in scars and lesions. For a young adult, his voice is coarse and almost indelible. It is most likely, the effect of the many drugs he must take to numb the pain of never-ending blows and stay fighting.

“I came to fighting through the late Garba Dan Garmun Garkawa”, Sharif tells us. We are atop an abandoned rooftop by a ravine in Berger, a short walk from the border between Lagos and Ogun States.

The boy Sharif became a man in Kano. It is Nigeria’s second largest city, the commercial nerve of the Sokoto Caliphate and now the North of Nigeria, where Dambe has become enshrined in local popular culture.

“As a child, Dan Garba loved me. When I used to enter Alawata house, I see people fighting with my own eyes and that’s why I started fighting”, he tells me.

In Kano, he learned and fought through weight classes and rose through the ranks. He and his trainers decided that if he was to become better, he would have to move closer to home.

Even though his diction is near-perfect Hausa and there is no hint of imitation in his mannerisms, Sheriff is Yoruba, from Ogun State.

He was born to a trader in Kosofe, where rival cult wars in the area and notorious secondary schools like Kosofe College and Ayedere Ajibola High School chiseled him through childhood.

Shariff was fighting in the streets long before he heard about Dambe.

“I have always desired to fight”, he says. “Even as a child, they always went to report to my mother that “Sharif had broken someone’s head”, or “Sharif had broken someone’s mouth, I was really stubborn”.

Brute power, tenacity, and endurance are the core of Dambe fighters. But in a sport where drawing blood elicits both cheer and pride, they are never enough.

“When I am ready to fight, I go to my teacher to pray for me, against who I will fight and if I am lucky, they give me something to compliment the prayer.”, he says.

This “something” is usually an amulet, a small black pouch of the size to tie around a finger. Wearing amulets and rings is usually a matter of choice, but all fighters have a long trail of incisions along their arms.

“These are Medicine,”, Sharif says when I ask him what they are. “They rip my arm and put them into my bloodstream, once it enters my bloodstream, it stays permanently”.

ALSO READ: How traditional marriage is done in Hausa-land

“Permanently” means that at any sign of aggression, Dambe fighters are almost always ready to beat the aggressor down. While some can be jovial and chummy, like Sharif when he talks about his upbringing in Kosofe, the ethos of the fight becomes a part of them.

This brutal way of life is not simply a charitable testament to Hausa tradition or a labor of love. Money exchanges hands at the arenas where they fight, in gate fees, sponsorship from local and state governments or prize money donated by a largely-informal association that regulates the sport on a national level.

Sharif makes a living off his fights.

“They used to pay 36 thousand naira before”, he says, “and I have been fighting for about 3 years, now they pay 48 thousand naira.”

It is good money by some standard, but it is not even enough to keep things going. His mother trades in Ojere Market, and he drops off a few thousand naira on any of his weekly visits.

But it’s not just about the money for Sharif; there is an impression that he fights in spite of his better judgment. He is naturally combative, a trait he showed when in the middle of our interview, his trainer began to bark orders to him to leave. He shouted right back.

In this brutal variant of boxing, he finds release for a perpetual aggression that only fades in small, random spurts.

It carries him through the violent beatings he receives and metes out. But not every Dambe fighter has enough of what they need.

Fighters can suffer life-threatening injuries, or leave the arena as vegetables. Some are not so lucky; a blow can hit a fighter to the ground, never to rise again.

“My friends that fight that I know of who have died are up to 20, or 15,”, Sharif remembers. “Even the one we fought with was lucky, he was close to dying, but he got ill, and is now condemned”.

For the hundreds of thousands who gather in open arenas to watch these gory duels, Dambe is a part of tradition that has all the elements of the perfect spectator sport.

The brutality of the spectacle is undeniable; most fighters are covered in wounds, a cocktail of drugs swimming through their system as they practice with actual body blows in the sun.

“I am not afraid, I must die eventually”, Sharif says. “The moment I decided to take up this profession, I decided to trust in God because this fight is very risky”

Strong words, but with time, this lifestyle takes a toll on their bodies. The lifespan of the fighter’s career is short; by their mid to late 20s, senior fighters retire to other means of earning a livelihood.

Some completely reintegrate into civil society and become traders or businessmen. For others, this brutish life is an endless course. They channel their physical energy in some way, working as guards or training young fighters.

As we talk about the fates of these fighters, Sharif tells me he’s had enough of the sport.

It will take him time to leave, he is already committed to competitions. He must find a means of livelihood once he unties the tightly-knotted cloth for the last time. But once he can manage an alternative, he’s out.

“I intend to get married eventually. After one or two years, by God’s grace I want to stop”, he adds.

As with any other person, his dreams are valid and Sharif knows. He has already told his trainer of his plans and has begun to explore his options. He knows what he needs to do, but he’s still some way off.

For now, he practices in a training camp near Ikorodu on the outskirts of Lagos for the next National competition; running through the drills, throwing his fist at anything and anyone he sees, all the while with thoughts of a new life in his head.

Fighters in the Dambe tradition live very extreme lives. They will do almost anything for the glory of victory. Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS