By Solberg Horve MISHIWO

In 1957, Ghana stood tall as the black star of Africa, rich in cocoa, gold, and promise. Its independence was celebrated as the dawn of African prosperity. Yet today, nearly seven decades later, Ghana’s economic narrative has become one of repeated cycles, boom and bust, reform and relapse, sovereignty and dependence. In a recent report titled “Transforming Ghana in a Generation,” the World Bank observes that 40 of the 68 years since Ghana’s independence have been spent under the supervision of the International Monetary Fund through 17 distinct programs. This startling reality forces a deeper question: has Ghana’s long courtship with the IMF been a partnership for progress, or a pathway to perpetual dependence? These questions about Ghana’s dependency are not rhetorical. They are written in the country’s economic history, which Figure 1 below captures through the sequence of IMF interventions from 1966 to date.

Figure1: Ghana’s IMF Programs Timeline (1966-2025)

The Numbers Tell a Story

Ghana’s per capita income has remained relatively stable at approximately US$2,200 over the past decade. The ratio of the country’s debt to GDP decreased from 92.6 percent in 2022 to 70.5 percent in 2024 because of the government’s debt restructuring plan. In 2022, 46.7% of the population was residing in multidimensional poverty, a situation that is slightly worse than in previous years. Nevertheless, the three northern regions of Ghana are home to more than 50% of the population, much of whom lives in acute poverty.

Ghana’s export system is one of the most concerning aspects. In the 2024 trade report from the Ghana Statistical Service, the three primary exports that generated the most revenue for Ghana were oil, gold, and cocoa. Crude petroleum lubricants accounted for GH?52.58 billion (17.8 percent), cocoa for GH?21.55 billion (8.4 percent), and gold bullion for GH?162.99 billion (55.3 percent of all exports). While Ghana is susceptible to fluctuations in global commodity prices due to its high concentration, the IMF’s forty-year reform programs have also underscored the difficulty of diversification.

The First Crisis: Seeds of Dependency

The International Monetary Fund and Ghana initiated cooperation shortly after Kwame Nkrumah’s removal from office in 1966.The military government implemented a “standby arrangement” between 1966 and 1969 to prevent the economy from “virtually collapsing”. With inconsistent economic policies and trajectory, by 1982–1983, Ghana’s economy had nearly collapsed. The country’s per capita income was one-third lower than it had been a decade prior, inflation was at 123 percent, and there was no longer any foreign currency on hand. The parallel market exchange rate was nearly twenty times higher than the official rate, and cocoa production had decreased to less than one-third of its previous level. This led to the initiation of the Economic Recovery initiative, Ghana’s most significant IMF-supported program in August 1983. In the nine years that followed (1983–1992), Ghana served as a model for other African countries that were simultaneously undertaking structural reform.

The ERP Era: Success or False Dawn?

Ghana’s political, social, and economic trajectory underwent a significant transformation in 1983 as a result of the Economic Recovery Program (ERP) of the International Monetary Fund. The program prioritized the promotion of the export sector and the implementation of fiscal discipline in order to eliminate budget deficits. GDP growth increased significantly from a negative 6.9 percent in 1983 to 5.2 percent in 1984. Ghana’s implementation of a Structural Adjustment Program was recognized as the most successful in Africa by the IMF and World Bank. By the conclusion of 1991, inflation had decreased from 143 percent in 1983 to 10 percent as a result of the program. Ghana’s poverty rate decreased from 52.7 percent in 1991 to 24.2 percent in 2012, a remarkable achievement during the 1990s.

On the other hand, critics contend that this triumph was achieved at a substantial expense. The implementation of austerity measures led to a decrease in financing for critical social sectors, including infrastructure development, education, and healthcare. The agricultural sector, with the exception of cocoa rehabilitation, received less than six percent of the anticipated funding. This had a notably detrimental impact on employment prospects in regions that did not produce cocoa, as agriculture employed over 65% of the population.

Research demonstrates that adjustment programmes established a debt trap. The government was spending approximately four times more on debt servicing than on healthcare at the peak of structural adjustment. The primary purpose of export revenue was to service obligations, and the export effort was unable to generate sufficient funds to cover interest payments. Due to the potential for default, Ghana was compelled to obtain additional loans, which were contingent upon the continued implementation of adjustment measures that were the primary cause of the country’s growing debt.

The Pattern Repeats

From 1995 to 1999 and 1999 to 2002, Ghana was once again subject to IMF programmes, despite the appearance of a prosperous ERP era. In 2003, President John Kufuor returned Ghana to the IMF as a Highly Indebted Poor Country (HIPC). Ghana’s debt repayment was contingent upon the implementation of the HIPC program. The national debt was US$23 billion in 2006, a decrease from $66 billion in 2005. This pattern endured until the 2010s. Ghana experienced an extensive power disruption during the 2015 presidency of John Dramani Mahama, which was referred to as “Dumsor.” Simultaneously, inflation was widespread, the currency experienced a decline in value, and the current account and budget deficits grew. The three-year program (2015-2019) helped restore macroeconomic stability, with growth projected to rise to 8.8 percent in 2019 from 2.2 percent in 2015, and inflation projected to fall to 8 percent from almost 19 percent. Yet once again, the gains proved temporary. By 2022, Ghana faced its most severe crisis since the 1980s, culminating in a sovereign default.

The 2022 Crisis: History Repeating

The 2022 crisis exposed significant deficiencies in the framework. The Ministry of Finance (MoF) unexpectedly announced on 24 November 2022 that the total public debt, which included state-owned firms, exceeded 100 percent of GDP. This announcement was made in conjunction with the domestic debt restructuring (DDEP). Eleven days prior, the percentage had been 75.9 percent. The energy sector had failed to make payments totaling an estimated 3.1 percent of GDP, and the Cocoa Board had accumulated substantial debt, according to subsequent IMF studies. The COVID-19 pandemic, more stringent global financial conditions, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine all contributed to the exacerbation of budgetary and debt issues. The government turned to monetary financing by the Bank of Ghana, triggering an acute crisis. GDP growth declined to 3.8 percent in 2022, and inflation reached a record high of 54 percent in December of that year. The cedi’s value plummeted by 60 percent.

The Current Programme: Different This Time?

In May 2023, the International Monetary Fund pledged to lend $3 billion to Ghana as part of a 36-month Extended Credit Facility (ECF). As of July 2025, Ghana has received approximately US$2.3 billion in disbursements following completion of the fourth review. The program’s three primary objectives are to restore overall economic stability, ensure debt sustainability, and establish the foundation for more equitable, rapid development. Early results show signs of stabilization. Economic growth recovered to 5.7 percent in 2024 and maintained 5.3 percent in the first quarter of 2025. Inflation declined from 54 percent in December 2022 to 18.4 percent by May 2025. The budget deficit in 2023 was 4.5 percent of GDP, a decrease from 11.8 percent in 2022. Ghana signed an MoU and executed a Eurobond swap for $13 billion in 2024 with the Official Creditor Committee’s approval.

However, significant issues emerged toward the end of 2024. According to preliminary financial statistics, the quantity of outstanding bills experienced a substantial rise in the months preceding the 2024 general elections. In the energy, tax, and financial sectors, numerous legislative initiatives and modifications were postponed. The newly elected government of 2025 was able to accomplish a fiscal primary surplus of 1.5 percent of GDP reducing excessive expenditure and identifying new revenue streams.

Table 2: Key Economic Indicators – Crisis vs Recovery Periods

| Indicator | 1983 (Pre-ERP) | 1991 (Post-ERP) | 2015 (Pre-Program) | 2019 (Post-Program) | 2022 (Crisis) | 2024 (Current) |

| GDP Growth (%) | -6.9 | 5.1 | 2.2 | 6.5 | 3.8 | 5.7 |

| Inflation (%) | 123 | 10 | 17.2 | 7.1 | 54 (peak) | 18.4 |

| Debt-to-GDP (%) | ~50 | ~35 | 71.8 | 62.9 | 92.6 | 70.5 |

| Fiscal Deficit (% GDP) | ~14.5 | ~1.8 | 5.3 | 4.7 | 11.8 | 4.5 |

| Poverty Rate (%) | ~50 | 52.7 | 24.2 | ~21 | 46.7 | 53.3 (projected) |

| Per Capita Income ($) | ~400 | ~450 | 1,858 | 2,202 | 2,206 | 2,200 |

The Social Cost of Conditionalities

The social impact of IMF programs has been consistently criticized, despite their success in attaining short-term macroeconomic stabilization. Typically, austerity measures involve the reduction of government expenditure, the elimination of subsidies, and the imposition of additional taxation. This has led to a decrease in funding for infrastructure development, education, and healthcare in Ghana.

The cost of essential commodities, including petroleum and food, has increased as a result of the reduction in subsidies. This has made it more difficult for low-income households to meet their fundamental requirements. Many Ghanaians have been left without support during economic hardship due to the absence of robust social safety nets.

Professor Godfred Bokpin of the University of Ghana has issued a warning that the current IMF programme encompasses a more profound level of adjustment that impacts not only government policies but also private sector enterprises and individuals. Public sector employment and wage restrictions, in conjunction with increased taxes to support domestic revenue, result in unemployment and diminished disposable income, causing hardship for families and workers.

To its credit, the current program includes specific protections for vulnerable populations. Spending on key social programs is protected and monitored through indicative targets. The Living Empowerment Against Poverty cash transfer program’s benefits were doubled in 2023 and then again in 2024. The Ghana School Feeding Program and National Health Insurance Scheme have received increased budgetary allocations. Nevertheless, critics contend that these measures are insufficient to mitigate the more extensive effects of austerity on Ghana’s populace, particularly the impoverished and marginalized.

The Geography of Inequality

Perhaps nowhere is Ghana’s development challenge more visible than in the stark regional disparities that persist despite four decades of IMF-supported reforms. While Greater Accra enjoys a poverty rate of just 2.8 percent, Ghana’s three northern regions namely Northern, Upper East, and Upper West, continue struggling with extreme poverty rates exceeding 50 percent.

This represents an 18-fold difference in living standards within a single nation.

The North-South divide reflects deeper structural issues that IMF programmes have consistently failed to address. The northern regions rely primarily on subsistence agriculture with limited infrastructure, poor road networks, and inadequate access to electricity and clean water. In contrast, the southern regions benefit from mining operations, oil extraction, cocoa production, services sectors, and better connectivity to international markets.

Figure 2 illustrates Ghana’s geography of inequality, showing how economic and social disparities are spatially entrenched across regions, with persistent poverty pockets contrasting sharply with areas of relative prosperity.

Figure 2: Regional Poverty Disparities in Ghana

The Structural Problem: Why Can’t Ghana Break Free?

Academic research reveals a troubling pattern. Studies examining Ghana’s historical engagement with the IMF show that bailouts often have short-term impacts on macroeconomic stability and growth, but effects are unsustainable in the long term, especially after IMF programs end. Below are identified key structural problems:

- Fiscal Indiscipline: The IMF estimates that fiscal deficits increased by over three percent of GDP each year on average in the past 12 years across three electoral cycles. Political pressures, particularly around elections, consistently lead to spending increases that undermine fiscal consolidation.

- Weak Domestic Revenue Mobilization: Ghana raised revenue equal to 13 percent of GDP in 2021, well below its estimated capacity of 21 percent and below the sub-Saharan Africa average. In the first half of 2025, revenue reached only 7.1 percent of GDP, falling short of the 7.3 percent target.

- State-Owned Enterprise Losses: Energy and cocoa sector state-owned enterprises continue imposing significant burdens on public finances. The Electricity Company of Ghana has accumulated arrears despite annual transfers exceeding US$1 billion. The Ghana Cocoa Board’s debt rose to US$1.8 billion in 2024 even amid record global cocoa prices.

- Limited Economic Diversification: Despite four decades of reform programs, Ghana’s economy remains heavily dependent on commodity exports. The service sector has grown but largely in low-productivity informal activities. Between 2012 and 2023, only 250,000 net jobs were created, most in low-productivity sectors.

- Governance Challenges: Persistent governance failures, inefficiencies, and corruption continue eroding trust and obstructing policy reforms. Weak institutions struggle to implement and sustain reforms across political transitions.

The Path Forward: Breaking the Cycle

Breaking free from IMF dependency requires addressing root causes rather than symptoms. To address the root causes, Government of Ghana must focus on the following:

- Fiscal Responsibility Framework: Ghana requires better fiscal regulations that have powerful enforcement systems that cut across electoral periods. The improved fiscal responsibility system in 2025 is a step improving but it will be imperative to execute it.

- Revenue Enhancement: Ghana needs to seal the difference between the current revenue disbursement (13 percent of GDP) and projected capacity (21 percent). This needs an overall tax reform, better management, rationalization of exemptions, and extension of the tax base beyond the formal sector.

- Economic Diversification: Ghana should have planned industrial policy so that it can establish competitive non-resource sectors. This involves investments in the agro-processing, manufacturing, digital economy and services sectors which are capable of providing quality jobs and limiting reliance on commodities.

- Institution Building: A robust institutionalization to manage the economy and make industries more transparent and better managed on the financial side and capacity building of the domestic would be vital to the sustainable implementation of policies.

- State-Owned Enterprise Reform: Chronic loss taking in the energy and cocoa sectors to be addressed by establishing performance management, accountability as well as strategic partnership where feasible or privatization.

- Political Economy Reflections: It is possible to make certain the continuity of policies to different administrations by developing larger political and social consensus around changes in the major reforms. The so-called Ghana Compact that the officials of World Bank are proposing might provide the non-negotiable priorities such as macro-fiscal stability, energy reform, and governance.

Conclusion: Partnership or Perpetual Dependency?

The question on whether the relationship is one of partnership or lifelong dependence remains complicated after studying 40 years of IMF involvement. The evidence suggests elements of both. IMF programs have been effective in several instances of ensuring that Ghana was not doomed to the total economic ruin, bought time so that reforms could be realized, and lent a hand to poverty alleviation in times of extended implementation. The policy structures and technical assistance have also helped in development of the institutions. Social spending protection in new programs demonstrates the development in the IMF thought.

Yet, the repetition of IMF programs in Ghana 17 times in 68 years means that fundamental structural issues that go beyond bailouts are occurring. The regular tendency toward reform and relapse implies that IMF conditionalities though effectively stabilizing the situation in the short run are not sufficient to meet the political economy thresholds and alteration of the structural approach to the diversity of the development.

The problem needing solving by Ghana is not merely a matter of technicality but of politics and institutions. To stop the cycle, there is a need to go beyond the IMF programs as the fast fixes to structural change and transformation. This involves making tough decisions regarding allocation of resources, compromising the present to benefit the future, institute institutions that are not easily busted by political whims, and good economic diversification.

The continuance of the Ghana-IMF relationship as one that is based on never-ending dependency or one of actual partnership will become clear in the next three to five years, or the country will be in preparation of its 18th program in the coming decades. Whether the IMF relationship is more a partnership or a continued dependency will always depend on how Ghana will manage to build the capacity as a country to build its domestic political will, institutional strength and economic fundamentals that will ensure that external supervision is not necessary. Until such transformation happens, the cycle will most likely persist, and the question will continue to be an unpleasant reality to generations yet to come.

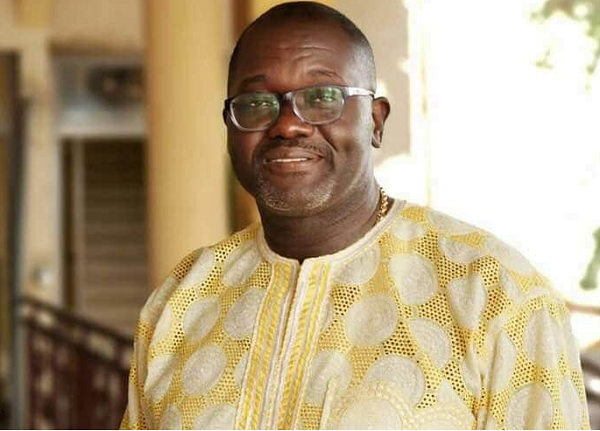

The writer is a Chartered Accountant (CA) and Chartered Tax Practitioner (CTP) with extensive experience in finance, auditing, taxation and management consulting. As a Partner at A.B Coffie (Chartered Accountants), he champions engagement quality, governance and value-for-money reviews, bringing policy-relevant insights to debates on fiscal sustainability and development issues.

He can be reached via:

Mobile: 0248 887 053

Email: [email protected]

References:

International Monetary Fund (IMF). III Ghana, 1983–91 in: Adjustment for Growth. Retrieved from https://www.elibrary.imf.org/display/book/9781557755667/C3.xml

World Bank. (2025, September). 2025 Policy Notes: Transforming Ghana in a Generation. News Ghana. Retrieved from https://www.newsghana.com.gh/world-bank-says-ghana-has-spent-40-of-68-years-under-imf-programmes/

African Development Bank. (2024, July 31). Ghana Economic Outlook. Retrieved from https://www.afdb.org/en/countries/west-africa/ghana/ghana-economic-outlook

World Bank. (2025). Ghana Overview: Development News, Research, Data. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/ghana/overview

Ghana Statistical Service. (2025, February). 2024 Trade Full Year Report. Citi Newsroom. Retrieved from https://citinewsroom.com/2025/03/gold-crude-oil-and-cocoa-dominate-ghanas-2024-export-earnings/

GhanaWeb. (2024, January 27). From Nkrumah to Akufo-Addo: Here are all the 17 times Ghana ran to the IMF. Retrieved from https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/From-Nkrumah-to-Akufo-Addo-Here-are-all-the-17-times-Ghana-ran-to-IMF-1769252

IMF. III Ghana, 1983–91 in: Adjustment for Growth

IMF. Ghana: Economic Development in a Democratic Environment—IMF Occasional Paper No. 199

Mensah, Conditional Development: Ghana Crippled by Structural Adjustment Programmes.

Business24 Online. Role of IMF and Ghana’s history of IMF bailouts.

IMF. IMF Lending Case Study: Ghana. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/GHA/ghana-lending-case-study

IMF. (2023, May). Ghana: Request for an Arrangement Under the Extended Credit Facility—Debt Sustainability Analysis. IMF Staff Country Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 168.

GhanaWeb. (2024, February 5). The detrimental impact of IMF conditionalities on the people of Ghana. Retrieved from https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/features/The-detrimental-impact-of-IMF-conditionalities-on-the-people-of-Ghana-1915174

Opportunity International. Learn facts about Ghana, Poverty, and Development. Retrieved from https://opportunity.org/our-impact/where-we-work/ghana-facts-about-poverty

The post 40-year affair with the IMF: Partnership for progress or perpetual dependency? appeared first on The Business & Financial Times.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS