By Nana Sifa TWUM, PhD

Boardrooms are intended to serve as the ultimate safeguard for an organisation’s long-term interests, functioning as spaces where independent judgment, fiduciary duties, and rigorous scrutiny uphold public trust and organisational integrity.

However, in Ghana, analogous to numerous other nations, the quality of corporate governance is frequently compromised by two interconnected issues: the politicisation of board appointments by successive governments and destructive turf wars that occasionally emerge between chairpersons and chief executive officers.

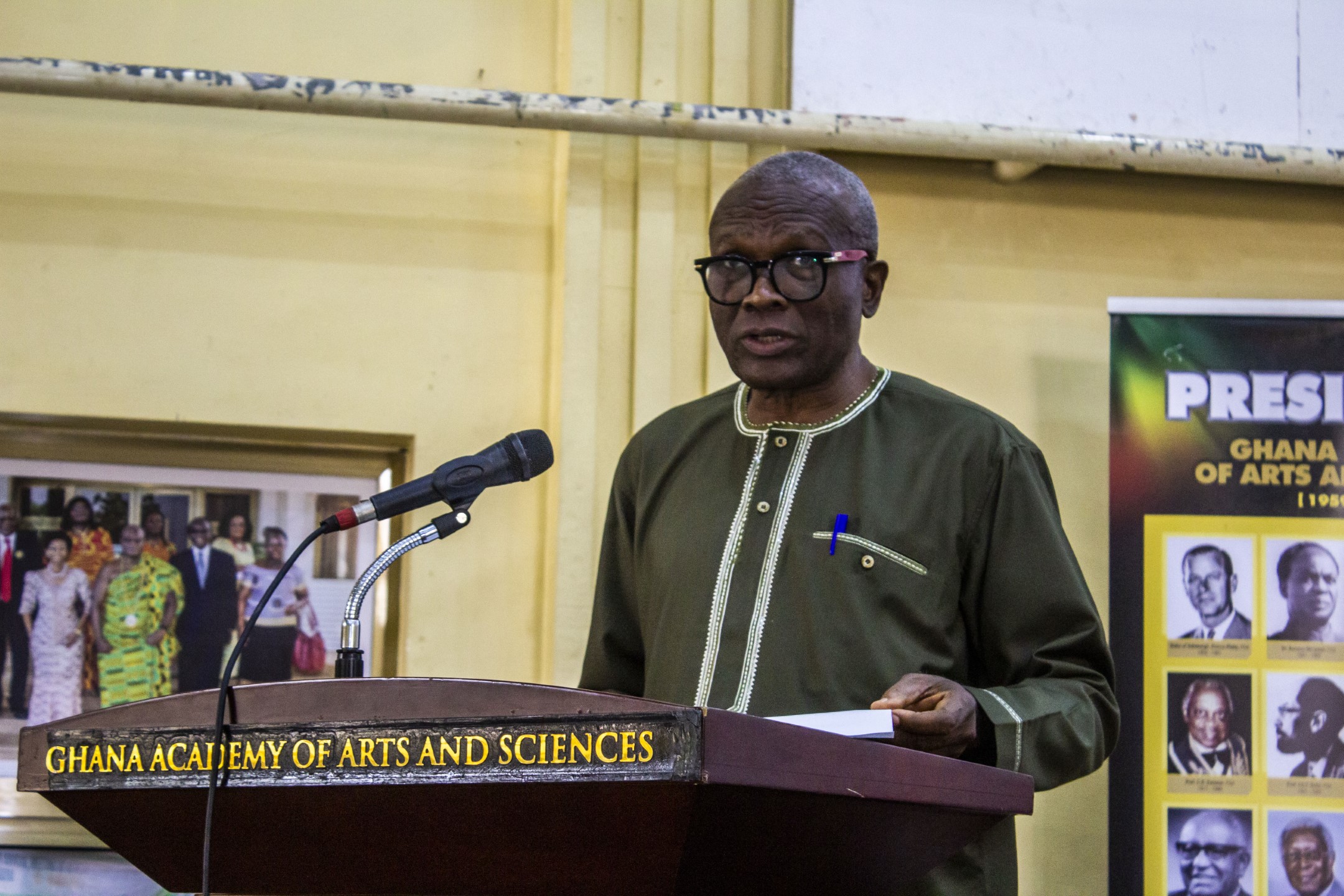

Both issues were prominently addressed at the recent Boardroom Governance Summit in Accra, held on October 14, 2025, and warrant urgent public discussion.

Political appointments: loyalty over competence

An effective and functional board necessitates a diverse range of skills, including industry knowledge, financial literacy, legal and regulatory expertise, and the moral courage to hold management accountable. Challenges arise when these positions are regarded as patronage rewards.

Political leaders occasionally appoint party loyalists, campaign supporters, or former officials whose main qualification is loyalty rather than relevant expertise. Such practices compromise the independence of the board and risk transforming it into an echo chamber that primarily serves the interests of the appointing authority rather than those of the public or shareholders.

What causes this phenomenon? It is partly attributable to appointments acting as incentives for political support, and partly because political actors believe that having close allies on boards will facilitate policy implementation. However, this trade-off entails considerable costs: boards lacking technical expertise often fail to identify substandard projects, approve risky transactions without proper due diligence, tolerate weak internal controls, and cultivate environments susceptible to corruption or mismanagement. Recent insights from governance practitioners and public officials have underscored these risks, cautioning that poor boardroom practices may jeopardise major national initiatives and diminish public confidence.

A pragmatic downstream implication is that organisations governed by politically appointed boards frequently encounter difficulties in attracting and retaining credible executives. Skilled Chief Executive Officers favour professional boards that acknowledge their roles and provide strategic guidance, rather than boards that micromanage or lack the requisite expertise to address complex operational challenges. This undermines institutional capacity and results in increased turnover at the executive level, thereby further impairing organisational performance.

The Board Chair versus the Managing Director: When roles blur and conflict erupts

A second recurring issue is role confusion and personality conflict between the chair of the board and the Managing Director or Chief Executive Officer (CEO). Governance theory is clear: the board, led by the chair, provides strategic oversight, while the CEO implements strategy and manages daily operations. When these boundaries become blurred, organisations risk falling into unnecessary power struggles.

Two distinct patterns emerge. Firstly, certain chairs—often former executives or politically appointed individuals who believe they retain operational instincts—overreach and attempt to manage the organisation from the boardroom. Secondly, some chief executive officers interpret their mandate as a licence to marginalise the chair or resist legitimate oversight.

In either scenario, the result is paralysis: strategic decisions are delayed, managers focus on internal politics rather than service delivery, and external stakeholders, including investors, clients, and citizens, suffer the consequences. Governance scholars have long examined the dynamics of trust and distrust between chairs and chief executives; failures in that relationship systematically undermine board effectiveness.

In public sector boards, where political pressure and patronage are already evident, these tensions are intensified. A chairperson, who depends on a political patron for their position, might be reluctant to confront a CEO with substantial political support; likewise, a CEO with significant political backing may disregard a chair’s guidance, leading to a detrimental tug-of-war that diverts attention and undermines organisational vitality.

The civic and fiscal costs

The repercussions of politicised appointments and conflicts between chairpersons and CEOs are evident. Poor governance results in defective procurement processes, inadequate project oversight, compromised service provision, and occasionally outright scandals, all of which diminish public trust and increase financial pressures on the state. Public appeals for improved ethical governance and the formation of more professional boards highlight the urgency of the issue and the need for reform.

What good governance looks like — and how to achieve it

Fortunately, solutions are simple in principle, although they present greater challenges in political practice. Summit and governance analysts have identified several key pillars that require more consistent implementation.

Merit-based appointments. Establish transparent selection criteria and publicise the skills required for each board role. When possible, use independent nomination committees or third-party vetting to minimise cronyism. Countries and organisations that professionalise appointments tend to see better board performance.

Clear role definitions and handbooks. A formal board charter outlining the distinct roles and responsibilities of the chair, the board, and the CEO helps prevent role creep. Regular inductions and refresher training assist chairs and CEOs in understanding healthy boundaries.

Skills matrices and term limits. Boards should maintain a skills register and recruit to address identified gaps, rather than randomly appointing candidates. Fixed, non-renewable term limits lessen the incentive to serve political patrons and encourage renewal.

Performance evaluation. Regular, independent assessments of the board, the chair, and the CEO foster accountability. Evaluations should be transparent enough to discourage complacency but confidential enough to allow honest feedback.

Ethics and conflict-of-interest rules. Strong disclosure rules and conflict-management procedures are essential, particularly for public-sector bodies where political ties are prevalent.

Culture of robust challenge, not rancour. Boards must encourage rigorous debate while safeguarding the chief executive’s mandate to operate. Chairs should be trained in facilitation and in adjudicating disputes impartially.

The way ahead

Boards are not merely ornamental; they serve as crucial governance mechanisms. When these mechanisms are impeded by political patronage or compromised by unnecessary personality conflicts, organisations and, consequently, the public they serve, experience adverse effects.

The October 2025 Boardroom Governance Summit correctly emphasised the significance of effective chairmanship. Nevertheless, it is imperative that the wider discourse is translated into policy and practice, including transparent appointment procedures, professional board development, and a culture that prioritises competence over connections. The stakes are exceedingly high to accept anything less.

The post Boardroom governance: When politics and personality undermine oversight appeared first on The Business & Financial Times.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS