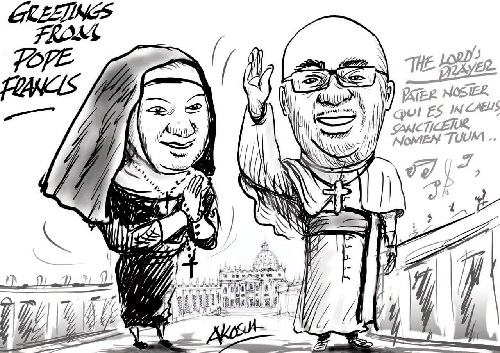

In the aftermath of Pope Francis’ passing on Easter Monday, a wave of hope and speculation has surged across Ghana and the African continent, with many rallying behind Cardinal Peter Kwodwo Appiah Turkson, Ghana’s own prominent prelate, as a potential successor to the papacy.

However, while such nationalistic fervour is understandable, it must be stated without ambiguity that neither Ghana, nor Africa, nor any sovereign nation or region can lawfully lobby or campaign for a papal candidate.

The election of the pope is governed by a unique and strictly regulated canonical legal framework, one that is deliberately insulated from geopolitical pressures and secular influence. To understand the gravity and sanctity of this process, it is important to examine the legal and institutional architecture that undergirds the election of the Bishop of Rome — The Pope.

The Legal Framework

Although the office of the pope is spiritual in character, its succession is regulated by a robust corpus of laws that can be likened to constitutional processes. The primary legal instruments are:

•The Code of Canon Law (1983), especially Canons 332 to 335, which define the nature of the papacy and the effects of a papal vacancy (sede vacante);

•Apostolic Constitution Universi Dominici Gregis (1996), promulgated by Pope John Paul II to govern the election of a new pope following a death or resignation;

•Apostolic Letter Normas Nonnullas (2013), issued motu proprio by Pope Benedict XVI to clarify and amend parts of the above.

Together, these documents form a constitutional regime for the Vatican, comparable — though not identical — to Ghana’s own 1992 Constitution, which provides for the lawful transition of presidential power. Just as in Ghana the electoral commission regulates general elections, the Catholic Church assigns this function to the College of Cardinals, acting under tightly controlled procedures.

The Role of the Camerlengo: Vatican’s Constitutional Custodian

Upon the death of the pope, the Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church assumes a role analogous to Ghana’s Chief Justice presiding over a transitional executive.

The Camerlengo officially certifies the pope’s death, notifies the Church and the world, seals the papal apartments, and manages the day-to-day affairs of the Vatican State during the period of interregnum.

However, like Ghana’s constitutional limitation on interim governments, the Camerlengo cannot make decisions that are the exclusive preserve of the pope.

This period is known as the sede vacante — Latin for “the seat being vacant” — during which the College of Cardinals is summoned to Rome to prepare for the conclave.

The Conclave: Secrecy, Law, and the Spirit

The conclave is the canonical electoral assembly, held in the Sistine Chapel, from which the public and all external influences are strictly excluded. Only cardinals under the age of 80 at the time of the pope’s death may vote.

This mirrors, in part, Ghana’s legal prescription under Article 94 of the 1992 Constitution, which sets eligibility criteria for Members of Parliament and by extension, ministers of state.

The voting procedure is exhaustive and governed by rigid rules:

•Each round of voting requires a two-thirds majority for a valid election;

•The ballots are cast in secret;

•If after several ballots no consensus is reached, provision is made for a run-off election between the two leading candidates, subject to modified voting thresholds as permitted under Normas Nonnullas.

No cardinal may vote for himself, and all electors take an oath of secrecy. Breach of this oath carries automatic excommunication, a legal penalty akin to being barred from office in civil jurisdictions.

The Sistine Chapel is thoroughly inspected to prevent surveillance or tampering — a ritual that could be likened to the vigilance demanded during Ghana’s election result collation, but with even greater legal and spiritual caution.

No Lobbying, No Endorsements: The Absolute Bar on Secular Interference

Historically, secular rulers sought to influence papal elections. This practice was conclusively condemned in 1903, when Pope Pius X issued the Constitution Commissum Nobis, forbidding any external influence on the election of the Roman Pontiff.

Today, Canon Law explicitly prohibits any civil or political interference, under pain of automatic excommunication (Canon 1331). The Ghanaian equivalent would be akin to criminalising executive influence in judicial appointments, to preserve the independence of the bench.

Therefore, while Ghanaians may fervently wish for Cardinal Appiah Turkson’s elevation, any act of lobbying, public campaigning, or diplomatic endorsement is both canonically illicit and procedurally irrelevant. The cardinals are called to discern under the guidance of the Holy Spirit — not political preference.

Acceptance and the “Habemus Papam” Moment

Once a candidate receives the required majority, the Dean of the College of Cardinals will ask: “Do you accept your canonical election as Supreme Pontiff?” Upon acceptance and declaration of a papal name, the individual becomes pope immediately, even before public announcement.

The newly elected pope is then introduced with the traditional proclamation: “Habemus Papam!” — We have a pope. He gives his first apostolic blessing from the balcony of St. Peter’s Basilica, similar in ceremonial importance to the swearing-in of a Ghanaian President at Independence Square, albeit with far deeper implications for the global Church.

Conclusion

The election of a Pope, though spiritual in meaning, is an exercise steeped in law, order, and precedent. It is a striking demonstration of how faith traditions can preserve institutional integrity through strict legal norms.

For Ghanaians, and indeed Africans, inspired by Cardinal Appiah Turkson’s towering moral and ecclesial stature, hope is not misplaced — but it must be tempered with reverence for the process.

To truly understand the journey to the papacy is to appreciate that in the Catholic Church, law and the divine are not strangers — they are co-labourers in the shaping of history.

By Gideon Kwasi Annor, President, Law Students’ Union, MountCrest University College

The post The death of Pope Francis and the canonical law of Papal succession: A Ghanaian legal reflection first appeared on 3News.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS