The International Criminal Court Tuesday acquitted former Côte d'Ivoire president Laurent Gbagbo of crimes against humanity in connection with post-election violence in 2010. His acquittal is the latest setback for the court's prosecutors after the collapse of other high profile cases.

"The court is really struggling to effectively investigate cases in complex settings in Africa," says Phil Clark, a lecturer at SOAS University in London.

"The ICC can go after suspects which is a good thing, but it can't actually pin criminal charges on them," he told RFI.

The charges against Gbagbo relate to the violence that erupted in 2010 after he refused to cede defeat to Alassane Ouattara in the presidential election of that year.

The clashes that followed left 3,000 people dead and 500,000 displaced.

But judges Tuesday said there was insufficient evidence to prove Gbagbo's guilt.

The court, which came into force in 2002 is "simply not equipped to deal with cases as the ones it's trying to tackle," comments Clark, who is also the author of a book on the ICC .

"The court has relied on Western investigators who don't understand the [African] terrain, and as a result, more ICC cases have collapsed even before or during trial that have actually reached the end of the trial. That really is a deep indictment of the ICC as a whole," he said.

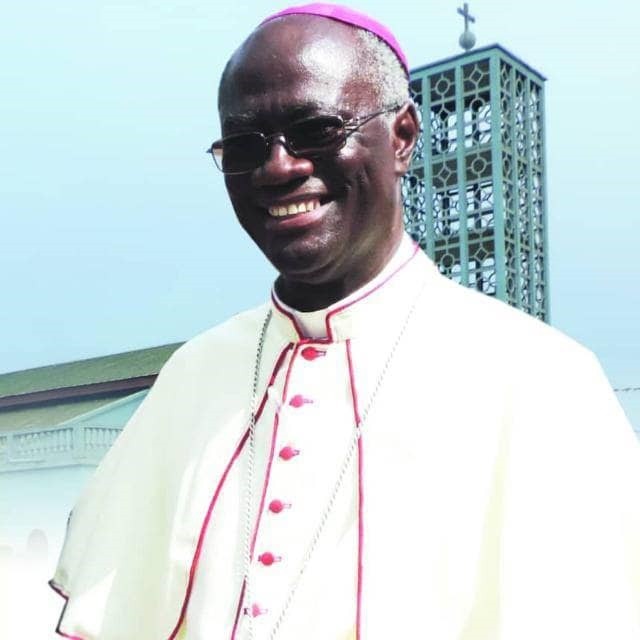

The office of ICC prosecutor Fatou Bensouda said the decision was "disappointing and unexpected", adding that the prosecution had the right to appeal.

Blow for justice

The prosecution is still reeling from the dramatic collapse last year of its case against Jean-Pierre Bemba, Congo's former vice-president for crimes against humanity in neighbouring Central African Republic.

That followed a previous setback in 2014, when the court was forced to drop charges against another state actor, Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta, also accused of election violence.

"It's a huge and historical failure for justice," reckons Florent Geel, Africa Director at the International Federation of Human Rights in Paris.

"Eight years on, we have the same players playing the same game," he told RFI, referring to Charles Blé Goudé, Gbagbo's right hand man who was also acquitted.

"Blé Goudé, Laurent Gbagbo, Alassane Ouattara, Simone Gbagbo, Guillaume Soro [former parliament speaker] have all been released, acquitted, or remain in power eight years later."

For the International Criminal Court, set up to hold the world's most powerful to account, the acquittal of Gbagbo, the first former head of state to be tried, and his right hand man raises deep questions about its ability to mete out justice.

This climate of "impunity" is echoed too in Côte d'Ivoire reckons Geel, referring to the amnesty granted to Gbagbo's wife, Simone last August by President Ouattara together with 800 prisoners. The move was described as an effort towards reconciliation.

Reconciliation now

For some Ivoirians that process will be helped by Gbagbo's release.

"A great part of the population was waiting for this decision," comments François Dali, an entrepreneur in Abidjan.

"I don't think it will bring the country back to war. However there could be some change in the political dynamics," he told RFI.

Gbagbo's political party the Ivorian Popular Front (FPI) has suffered without their leader during his seven-year stint behind bars. Dali reckons his return could boost the party.

"It was like a family waiting for the father. Now, the FPI will look for alliances and try to count in the 2020 elections."

Despite languishing in jail since 2011, Gbagbo still commands a strong following at home, with one daily Le Temps, referring to him as "the legend that never dies."

His return may also calm the wrath of supporters who always felt that his arrest, transfer and detention at the International Criminal Court at the Hague was a political decision , accusing former colonial power France, of plotting to force him out.

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS