Vital medicinal plants, which some 70% of Ghanaians rely on due to high costs of private healthcare, are being lost to illegal gold mines.

Vital medicinal plants, which some 70% of Ghanaians rely on due to high costs of private healthcare, are being lost to illegal gold mines.

In Kwabeng, in Ghana’s Eastern Region, young men and women wearing mud-splattered boots go back and forth on motorbikes and tricycles from the main road to the paths that go deep into the forest. Around them are acres of fruiting cocoa trees; swathes of thick green forests that stretch up hills as far as the eye can see. But nature is not these men and women’s immediate concern. Gold is. Illegal gold mining, to be exact, known as galamsey.

The illegal gold pits bring wealth to Ghana, directly employing over one million small-scale miners and accounting for 35% of the country’s gold production. With global gold prices having surged from around $1,800 per ounce in 2020 to over $4,000 in 2025, these illegal pits are a big boost for Ghana’s economy, and there are growing concerns that the government is sacrificing the environment to improve economic indicators and boost gold reserves.

But this wealth comes at the expense of health, in more ways than one. Some of illegal mining’s negative health impacts are well-reported, such as the contamination risk to local communities’ water, with galamasey having polluted at least 60% of Ghana’s rivers. Yet there is one particularly harmful effect that is still little known: the killing of the medicinal plants that 70% of Ghanaians depend on, particularly those Ghanaians who can’t afford modern healthcare.

Per a Ghana Statistical Service survey in 2019, 51.7% of Ghanaians seek consultations at private health facilities as against 45.7% in public facilities. The favouring of private services is attributed to the inadequate public health infrastructure, among others.

“When you destroy a forest, you destroy a pharmacy,” said Awula Serwah, a lawyer and coordinator of the Eco-conscious Citizens environmentalist group. “What people don’t seem to realise is that as a consequence of illegal mining, the peasant farmers are losing their livelihood. The fishermen are losing their livelihood.”

One gold-mining path in Kwabeng goes past Farida Mohammed’s home. The excavators are around 600 metres away; at certain times of the day, she can hear their hum as they claw through the earth in search of gold.

Mohammed is a popular traditional healer in the district, known for her use of medicinal plants to treat bone fractures. Mohammed inherited her calling, she told openDemocracy, and the most important plant she uses in her treatment is known locally as Kwaebesin.

Once widely available in the forests around her home, the plant known for speeding up bone formation and cell activation has disappeared in the last seven years as illegal gold mining intensified.

“Just behind my home, we could find the medicinal plants we needed,” said the worried healer. “But because of illegal mining, they are gone. The areas we were used to finding the plants were cleared.”

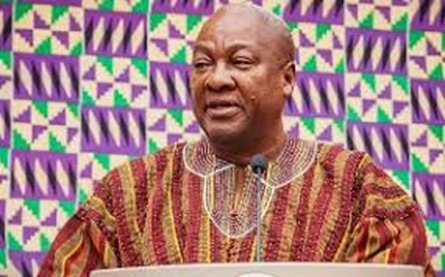

Serwah of the Eco-conscious Citizens believes the illegal gold mining is putting Ghana “on the verge of an ecological catastrophe”. Yet successive governments have been slow to act. President John Mahama was returned to power in January of this year after his predecessor, Nana Akufo-Addo, faced criticism for a lack of urgency in safeguarding the environment from illegal mining.

Before the election, Mahama promised to scrap a law allowing mining in forest reserves, but his government failed to act for almost 11 months until, under rising pressure from environmental activists, it finally started the process to revoke the law and convened a special forum to discuss the illegal mining problem.

Serwah attended the forum and left unsatisfied with the government’s posturing. “It was a good PR exercise. But did it answer our questions? Not really,” she said. She is among a group of activists demanding a state of emergency in areas affected by illegal mining, arguing that the wide-reaching devastation justifies this extreme demand.

Ghana has around 7.9 million hectares of forest cover, which makes up around 35% of its total land area. But the country also has one of the highest levels of deforestation in the world, having lost around 25% of its tree cover between 2001 and 2004 as the mechanisation of galamsey took shape. The loss has increased in recent years, with the United Nations Development Programme warning in 2023 that Ghana is now losing 135,000 hectares of forest cover annually – equivalent to 189,000 football pitches.

These forests are home to at least 1,360 species of medicinal plants for primary health care, which rural communities across Ghana are said to have accrued knowledge of. The plants treat a wide variety of ailments, including fever, malaria, wounds, gastrointestinal disease, numbness, hypertension, coughs, gonorrhea, syphilis, skin diseases, ulcers, rheumatism, asthma, and fibroids.

There may yet be more undiscovered plants that can treat more diseases, according to Dr Gladys Schwinger, a professor of botany at the University of Ghana. “We don’t know half of what we have in our forests, and now we may never know because they have been destroyed by galamsey.”

Deforestation for mines alters finely tuned microclimates, which makes it impossible for certain plants to reproduce or grow back after they are destroyed, as is the case with the kwaebesin Mohammed once sourced from the forests of Kwabeng.

Schwinger explains: “When the topsoil is removed, anything new can grow to succeed the plants. You won’t have the original vegetation that was there.”

Ghana’s Centre for Plant Medicine Research is the state institution in charge of herbal medicine research and development. But resource constraints have prevented it from making conservation interventions in areas affected by illegal mining, according to Michael Akuamoah-Boateng, the centre’s head of plant development.

Akuamoah-Boateng told openDemocracy that the centre is developing arboretums and medicinal gardens to start planting and protecting medicinal plants and produce herbal medication. It has three such gardens in Ghana’s Eastern Region, but to meet the urgency of the losses, the centre says it is working towards an arrangement where it can utilise forest reserves.

“What we are now trying to push for is that the Forestry Commission give us concessions,” Akuamoah-Boateng explained. “They can give us a portion, and we can cultivate the medicinal plants, which we can use as a form of conservation, and we can also harvest sustainably.”

The Environmental Protection Authority, which the government granted expanded powers to strengthen the preservation of ecosystems and biodiversity in January 2025, told openDemocracy that the medicinal plant losses were not specifically on its radar. “This is one area we have not really paid attention to,” said Hobson Agyapong, the authority’s principal programme officer.

Despite this, Agyapong confirmed Schwinger’s fears that certain ecosystems have been permanently altered. “If you go to most of the artisanal small-scale mining zones, almost all those original ecosystems are extinct,” he said.

While there aren’t any specific groups advocating for medicinal plant conservation, environmental activists are indirectly involved through their work. The founder of the Jema Anti-Galamsey Advocacy group in the Western Region, Reverend Father Joseph Blay, told openDemocracy that the anti-illegal mining activism he started a decade ago has helped to ensure his community still has access to its medicinal plants.

“We formed our own community task force to police the forests and protect the natural resources from illegal miners,” Blay said. “We [still] have a forest that is reserved for medicine, game and other things. The medicinal plants are there free for us because our land is pure.”

A hefty price being paid

For clients of traditional healer Farida Mohammed, her plant medicine is not only effective but the only choice they have, given the prohibitive cost of medical care in Ghana.

The healer was the saving grace of 31-year-old Edward Amoako when he broke bones in his thigh in a bus crash earlier this year. He was rushed to a hospital by first responders, but says he knew it would not be a realistic option for him. “The hospital mentioned a price for care I couldn’t afford; about 20,000 Ghanaian cedis ($1,823),” he said. While Amoako is still healing and needs crutches to help with movement, his condition has improved significantly since receiving care from Mohammed.

Prosper Teye, 23, also turned to Mohammed’s remedies in a last desperate attempt to save his right leg after a gnarly motorbike crash. “Doctors said they were going to amputate my leg,” he said. “After the road crash, my leg was basically falling off.” His trust in Mohammed’s herbal remedies is paying off so far, and with rehab going well, he expects to make a full recovery.

These days, though, Mohammed’s care is also becoming more expensive. The destruction of local medicinal plants means healers are being forced to buy them from industrious middlemen who source them from very remote areas of Ghana or even abroad. But no one can tell how long this arrangement can last.

Mohammed must now buy her kwaebesin from over 600 kilometres away in northwest Ghana for about GHS2,000 ($182) a sack – a cost she passes on to patients with much regret, charging on average GHS200 ($18) for treatment that was once free.

“[The illegal mining] really hurt us. We’re poor in this community. It may get to a time where if you break your leg, you will have to go to hospital and pay up,” Mohammed lamented.

At the Centre for Plant Medicine Research, scarcity is also driving up its costs of producing remedies. “We also buy plants from outside [Ghana] and we are having challenges getting some plants because people are saying the galamsey is destroying the trees,” says Akuamoah-Boateng. “Almost every year, suppliers come back for price renegotiations because the things are getting scarcer and expensive.”

He singles out two once popular plants that are no longer easy to find: ageratum conyzoides, a foul-smelling plant with ovate leaves used in treating over 20 ailments, including bone fractures, epilepsy and leprosy, and desmodium adscendens,which is used for issues ranging from asthma to even psychosis.

Perhaps worse than increased costs is the fear that what little medicinal plants remain may actually be poisoning those who use them due to the heavy metals used for processing gold seeping into the soil nearby. Areas with illegal mining have elevated levels of mercury, cyanide and arsenic in the environment.

A research paper in the Journal of Chemistry found heavy metals in 20 medicinal plants in the mining town of Obuasi, in southern Ghana. Bioaccumulation over time from repeatedly ingesting such plants could cause neurological disorders, cardiovascular issues, and congenital defects.

Herbal medication is tested for safety by the Food and Drugs Authority. But the raw medicinal plants being sold face little scrutiny. Akuamoah-Boateng warns: “If the people are getting the herbs from a galamsey site where there is a lot of mercury in the soil, the market people will not know and just sell it on.”

The popularity of medicinal plants means they end up in city centres, hundreds of miles from illegal mining areas.

Sekina Ninikai, for example, sources medicinal plant species to treat ailments ranging from fever, jaundice and hypertension from forests in south-west Ghana, arguably the area worst-hit by illegal mining. She trades them at the popular Nima market in Accra, Ghana’s capital, but cannot vouch for their purity.

“It worries me,” she told openDemocracy. “I take this medicine too. We are all in the mess.”

By Stephen Gyampo & Delali Adogla-Bessa

Published with permission

The post Ghana gold exports bring in more revenue, but medicinal plants are dying appeared first on Ghana Business News.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS