Stephen Mensah, a 90-year-old elder of Ewoyaa, a tiny community in Ghana’s Central Region, would soon lose the place he has called home for nearly a century.

If Ghana’s legislators approve a critical mining deal, greenlighting resource extraction, Mr Mensah, his family, and 400 residents of Ewoyaa will be forced to leave their ancestral land, leaving behind memories and livelihoods tied to the land.

Ewoyaa has become Ghana’s hotspot for lithium, a critical mineral for electric vehicles and renewable energy industries. A Mining Lease Agreement to mine the mineral in Ewoyaa is currently before Parliament, awaiting ratification required by Atlantic Lithium, a subsidiary of Australian-based Bowery GB, to start mining in the community.

This will displace the Ewoyaa people and cause environmental loss, including the destruction of farms, medicinal plants, and wildlife habitats.

Atlantic Lithium, which describes itself as an Africa-focused lithium exploration and development company, has already secured a Mine Operating Permit, issued by the Minerals Commission and a Land Use Certificate by the Mfantseman Municipal Assembly’s Spatial Planning Committee, authorizing the rezoning of the land within the Ewoyaa Lease Area for mining.

Plus, an Environmental Permit has been granted by the Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) for activities proposed in the company’s Mine and Process Environment Impact Statement and Water Use Permit, allowing extraction from the Ochi-Amissah River.

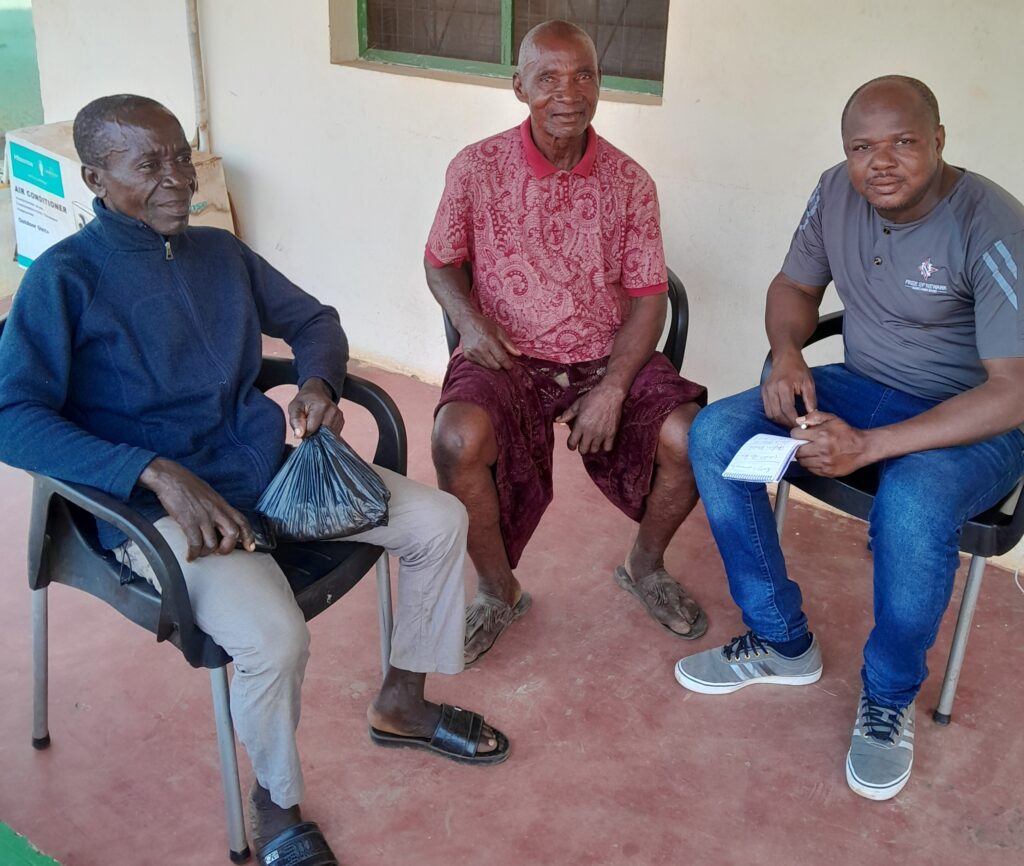

“In the meantime, we have been asked by Atlantic Lithium to stop building because it has been granted an operating permit and other mining rights to mine here,” Mr Mensah surrounded by other members of the village told African Eye Report.

During a visit to Ewoyaa, about 130 kilometres south of capital Accra, signs of impending change were visible. Several buildings, hencoops, pens, and nursery, among others were marked for demolition by the company with the approval of the Minerals Commission. Residents have been warned not to build or expand their homes.

“In the meantime, we have been asked by Atlantic Lithium to stop building because it has been granted an operating permit and other mining rights to mine here,” Mr Mensah surrounded by other members of the village told African Eye Report.

“The mine has started already but the company, Atlantic Lithium came here to discuss with us about their activities in the community and its surrounding communities.”

Residents say they feel stranded and uncertain about the future because of the delay in compensation and production of lithium. There’s also no certainty about a new site for their resettlement. Young people have started migrating to gold mining communities in other parts of the country struggling for livelihood.

“They keep telling us Parliament is yet to ratify the agreement,” said one resident. “But we see company workers digging and working in the bush every day. We don’t know what’s going on.”

They came to talk to us about our crops such as maize, cassava, farmlands, and animals, among others. Since they came and counted all our crops and marked our houses, nursery, pens, hencoops, and other belongings, they told us that they would come and pay the compensation. But up till now, we haven’t heard from them,” the resident said at the local chief’s palace.

The resident continued: “Officials of the Mankessim office of the company who frequent the community told us that the government is yet to ratify the lithium mining agreement and that they are waiting for the ratification. So, we members of the community are also waiting for them to pay our compensation.”

It has been over three years of uncertainty.

“But the workers of the company are always in the bush digging, and all sorts of things. So, we don’t know what is going on! So, we are very stranded and confused,” another resident said.

Another elder added: “The company came and stopped us from building. The officials said we should not continue to build. From that time up till now about two years, so we can’t build new houses, we can’t do maintenance, and we can’t expand our houses too.”

“My building is at the lintel stage but I can’t add anything to it again. I could have finished by now but because of the embargo on buildings in the community. The little money that I saved for the building has been spent. All the money has gone wasted,” said 60-year-old Uncle Ebow.

The community’s entire life has ground to a halt. They can’t build, farm, or hunt. It’s like life has come to a standstill for them.

“But the workers of the company are always in the bush digging, and all sorts of things. So, we don’t know what is going on! So, we are very stranded and confused,” another resident said.

“We can’t even do hunting too because the bush animals have run away due to the constant vehicular movement in the community,” Uncle Ebow lamented.

African Eye Report visited Atlantic Lithium’s Mankessim office, where senior officials confirmed that Ewoyaa’s residents would be relocated and resettled upon the start of production. However, they couldn’t specify where the community would be resettled, as discussions with stakeholders were ongoing.

Officials interviewed by African Eye Report were Superintendent of Land Access and Resettlement, Rexford A. Aboziah; Community Relations and Social Performance Manager, Dr Millicent Aning-Agyei; and the Community Development and Livelihood Officer, Berikisu Liman.

Compensation?

The officials also explained that the company had not paid compensation for the properties marked for demolition by the company yet because the compensation committee was still deliberating on it.

They explained that the compensation committee comprises traditional leaders, representatives of the community, a representative of the district assembly, a representative of the Minerals Commission, a representative of the company, and NGOs, among others.

Besides the uncertainties and impacts lamented by residents, industry experts warn that lithium mining could have severe environmental and social consequences, including biodiversity loss, water and air pollution, and livelihood disruption.

“There must be a Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) process,” said Denis Gyeyir, Africa Senior Programme Officer at the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI), who added that relocation of the community is necessary because of pollution.

Mr Gyeyir, however, stressed that the compensation package must cover the real value of the ancestral land and livelihoods lost.

“From our engagement, it is obvious that the issue of compensation is still a challenge because even the compensation package as determined by the Fees and Compensations that are approved by Parliament is so insignificant to be able to adequately compensate people who are affected by the mining,” he said.

He also raised concerns about the resettlement process.

“Are you going to ensure that their schools are available where you are relocating them? Are you going to ensure that their livelihoods and the support system they had are restored? For instance, if they were fetching firewood from the nearby forest, how are you going to ensure that they have a nearby forest to fetch firewood or what alternative sources of energy for cooking are you providing for them?

“What alternative sources of drinking water are you providing for them? So, there are a whole lot of assessments that have to be done. They have to be done based on the initial Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) that the community gives and the community must first of all be aware of the impact.

“The people must know the implications of relocation and resettlement before they agree to be relocated. If they don’t know the impact then what you have done is basically to deceive the community and gain access to the land,” the expert said.

Environmental Impact Assessment and community engagement

Atlantic Lithium conducted an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) as required by Ghana’s Environmental Assessment Regulations (1999). A public hearing was held in June 2024 to address environmental and health concerns.

Despite this, Mr Gyeyir and other civil society actors argue that the engagement process has been insufficient. “Most residents can’t read and understand a 200-page report,” Mr Gyeyir noted. “The company must properly explain the impacts in local languages.”

Ghana holds an estimated 180,000 tonnes of lithium reserves, ranking fourth in Africa behind the Democratic Republic of Congo (3,000,000 tonnes), Mali (840,000 tonnes), and Zimbabwe (690,000 tonnes).

Atlantic Lithium’s Ewoyaa project is expected to generate about $4.8 billion over the mine’s lifespan. The West African nation will receive a 13% carried interest, which is statutorily government’s stake in mining business concerns.

The company has also been listed on the stock exchange, allowing the public to invest in the project. A 1% revenue contribution to a community development fund is also to be paid to support local infrastructure and services.

However, Mr Gyeyrir warned that the midstream state, that is refining and processing, will produce additional toxic waste, increasing the environmental cost. “Lithium carbonate and hydroxide generate highly toxic waste,” he said. “If not properly managed, it will create long-term environmental damage.”

Meanwhile, Atlantic Lithium has continued to lobby officials for quick ratification of the deal. On February 19, 2025, company executives met with the Minister of Lands and Natural Resources, Emmanuel Armah-Kofi Buah, to push for the final ratification.

“We have secured all necessary permits and are awaiting parliamentary ratification,” company chair Neil Herbert said at the meeting, optimistic about securing the deal ultimately. “Once approved, we’ll advance toward the final investment decision.”

The economy of Ghana has long been natural resource-dependent, relying on earnings from cocoa, gold, bauxite, oil, and soon lithium. However, past mining agreements have often failed to deliver meaningful benefits to local communities, a situation that other resource-rich sub-Saharan nations have experienced.

If Atlantic Lithium’s project proceeds without adequate compensation and resettlement, Ewoyaa could become another example of resource extraction without development.

For the people of Ewoyaa, the lithium boom brings uncertainty as they wait in limbo, hoping that Ghana’s leaders will protect their rights and their future.

Nothing came of African Eye Report’s efforts to speak with government officials on this report.

By Masahudu Ankiilu Kunateh

African Eye Report with support from CJID

Used with permission

The post People of Ewoyaa to lose homes, biodiversity when Ghana Parliament approves lithium production appeared first on Ghana Business News.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS