In last week’s column, I revisited the classic cautionary tale of The Emperor’s New Clothes to highlight the dangers of groupthink, blind loyalty, and the unwillingness to speak truth to power.

The central lesson remains urgent for our times: a leader who surrounds himself with praise singers, or who accepts advice without subjecting it to careful scrutiny, risks presiding over decisions that could harm the very people he is sworn to serve.

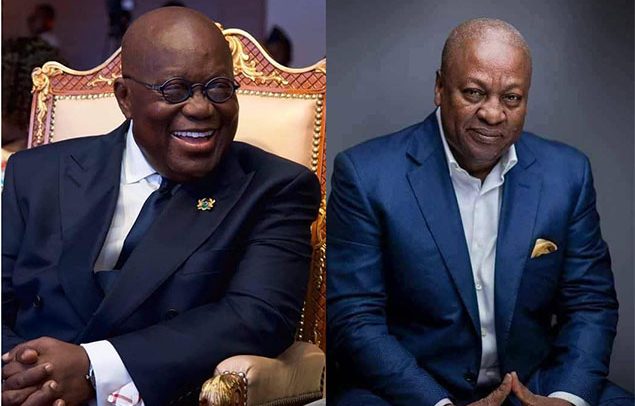

Today, I want to go a step further and address this directly to the highest office in the land—the Presidency. My appeal is simple: Mr. President, subject the advice you receive to rigorous testing. Seek a second and even third opinion if necessary. What matters is not partisan allegiance, not loyalty to a circle of advisors, but the ultimate delivery of policies and decisions in the public interest.

Why Scrutiny Matters

The Presidency is both a privilege and a burden. A President is daily besieged by streams of advice—some sound, some self-serving, others simply ill-informed. In such an environment, the temptation to rely on trusted inner circles is understandable. Yet, it is precisely in this setting that the danger of the “emperor’s new clothes” phenomenon looms large.

When trusted advisors are either unwilling or unable to tell hard truths, when decisions are taken based on expedience rather than evidence, the results can be disastrous. Policies that look polished on paper may fall flat in implementation. Well-meaning initiatives may suffer because practical realities were ignored. Worse still, some advice may be driven by hidden personal or political agenda that do not serve the nation as a whole.

This is not unique to Ghana. Around the world, history is littered with examples of leaders undone by faulty advice—from corporate boardrooms to State Houses. The lesson is universal: leadership without scrutiny is leadership exposed to costly error.

The Litmus Test of Public Interest

How then can the President guard against this danger? One way is to apply what I call the “litmus test of public interest.” Every piece of advice, every policy recommendation, should be measured against a single standard: Does this serve the majority of our people fairly and effectively?

Not: Does this make us look good politically?

Not: Does this serve a few well-connected interests?

But rather: Will this tangibly improve the lives of ordinary Ghanaians, from the farmer in Bunkpurugu to the trader in Kaneshie, from the teacher in Cape Coast to the nurse in Wa?

If the answer is not a clear “yes,” then caution is warranted.

This principle is non-partisan. It does not matter which party happens to be in government at a given time. Citizens, across divides, care most about delivery. They care about whether schools are well resourced, hospitals functional, roads motorable, and economic opportunities fairly distributed. The President, as custodian of the public trust, must therefore ensure that advice translates into outcomes that serve the many, not the few.

The Value of Second and Third Opinions

No leader, however brilliant, can be expert in every field. This is why the best leaders seek multiple perspectives before arriving at decisions. A second or third opinion is not a sign of weakness; it is a mark of wisdom.

In medicine, doctors often recommend a second opinion before a major operation. The stakes are too high to rely on a single diagnosis. In the same way, the stakes of governance—national stability, economic growth, social cohesion—are too high to rest on one adviser’s word.

The President should therefore institutionalise a culture of verification: consulting independent experts, engaging broad-based stakeholder groups, and even commissioning impact assessments before rolling out critical policies. This process, while sometimes slower, ultimately prevents missteps and builds trust.

Guarding Against the Court of Yes-Men

Every Presidency risks being captured by the so-called “court of yes-men”—a circle of officials and associates more eager to please than to probe. Such circles are dangerous because they feed the leader what he wants to hear, not what he needs to hear. They thrive on the leader’s dependence and fear that truth-telling might cost them their place at the table.

But the cost to the nation is far greater. A leader insulated from candid advice may misread the mood of the people, ignore brewing discontent, or pursue policies detached from lived realities. Eventually, this disconnect breeds cynicism, erodes trust, and destabilises governance itself.

The antidote is deliberate openness. The President must welcome dissenting views, reward candour, and even institutionalise mechanisms for critique. It must be safe for someone in the room to say, “Mr. President, this may not work as intended.”

Lessons from the Past

Our nation has already seen the consequences of insufficient scrutiny in policymaking. Ill-conceived programmes rolled out in haste have sometimes wasted scarce resources. In other cases, policies crafted in air-conditioned offices have failed to account for ground realities, leaving communities disillusioned.

Conversely, moments when leaders paused, sought broader input, and adjusted course have often yielded better results. These lessons must not be forgotten. The President’s legacy will depend not only on bold vision but also on the humility to test, refine, and improve decisions in light of diverse perspectives.

A Call for Institutional Strength

While the responsibility rests heavily on the President, institutions also matter. Advisory bodies, research institutions, think tanks, and Parliament itself must be empowered to provide independent scrutiny. Civil society, media, and academia have a role too, not as adversaries but as partners in the democratic project.

When leaders embrace scrutiny from these quarters, they not only safeguard themselves against error but also enrich the policy process with insights rooted in data, expertise, and citizen experience.

Beyond the Party Lens

It must be said again: this is not about one party or one administration. It is about the health of governance itself. Too often, political discourse in Ghana becomes trapped in partisan lenses, where every decision is judged by which party initiated it. But for citizens, the true measure is delivery.

When roads are built, when water flows, when businesses thrive, when jobs are created—citizens celebrate results, not party colours. The President, therefore, must rise above the partisan clamour and insist that advice, policies, and programmes be judged solely on their merit and their service to the public good.

Conclusion: Listening Twice

The parable of The Emperor’s New Clothes ends with a child breaking the silence and telling the obvious truth: the emperor is naked. In our governance today, we must ensure that the President never has to face such an embarrassing awakening.

This means cultivating an environment where advice is scrutinised, where the public interest is the litmus test, and where second and third opinions are sought as safeguards. It means resisting the lure of yes-men and embracing the power of candid counsel.

Above all, it means remembering that leadership is not about being flattered or shielded, but about being effective in delivering for the people.

So, Mr. President, listen once, but verify twice. In the end, the people of Ghana deserve nothing less.

The post Reflections by S .M.A: When leaders must listen twice appeared first on The Business & Financial Times.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS