By Dr Hene Aku KWAPONG

When it comes to public accountability, Ghana still relies far too much on trust where verification is required. In modern governance, integrity cannot be assumed; it must be proven. That is why asset declaration should no longer be a bureaucratic ritual, but a National Intelligence Bureau (NIB)–led process — one that certifies every public officeholder before they assume power.

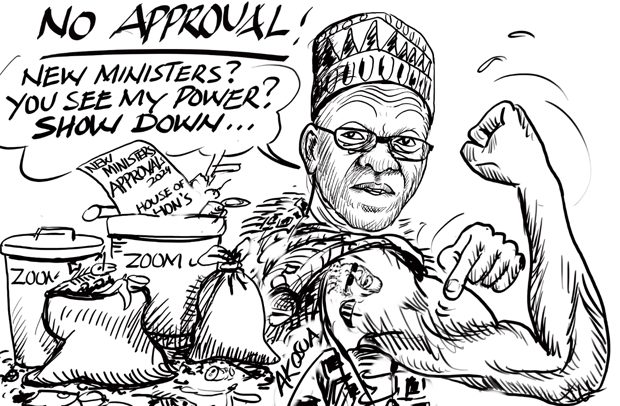

This reform has now become urgent and non-negotiable. In recent months, Ghanaians have witnessed an alarming flood of corruption scandals — theft, embezzlement, and misuse of public funds — by officials entrusted with national resources. Practically every week brings a new revelation of misappropriation or unaccounted wealth.

These incidents are not isolated; they are symptoms of a system that lacks transparency, verification, and deterrence. Without structural reform, the moral and fiscal cost of corruption will continue to erode national credibility and trust in governance.

I have seen how effective such systems can be. When I went through the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) clearance process for a public role in New York City, it was exhaustive — a full audit of my financial, professional, and personal integrity. It was not red tape. It was a firewall against corruption. Ghana — and every democracy that values public trust — deserves the same.

Beyond Paperwork: Making integrity verifiable

Let us be candid: Ghana’s current asset declaration regime has become largely ceremonial. Politicians fill out forms, deposit them at the Audit Service, and move on. There is little verification, minimal follow-up, and no serious deterrent.

Yet asset declaration is not about appraising how much someone is worth; it is about transparent disclosure of interests. It is not asset valuation — it is asset accountability. The goal is to establish a clear, factual baseline of what a public official owns before entering office. Without that baseline, there is no objective way to detect unexplained enrichment later.

By knowing what officials own at the start, citizens and oversight bodies can more easily track changes that suggest corruption. Asset declaration, then, is not an exercise in curiosity but a preventive instrument of integrity.

The BNI, with its investigative powers, access to financial intelligence, and authority to coordinate across agencies, is uniquely suited to own and certify this process. What Ghana needs is not more paperwork, but institutional verification.

A NIB-Certified System for Public Trust

Here is what a reformed system would look like:

- Every public office candidate — from minister to district assembly member — must undergo BNI-led asset verification before assuming office.

- Any undisclosed, inconsistent, or unverifiable asset leads to automatic disqualification.

- Completion and certification by the BNI becomes a constitutional prerequisite for appointment, election, or swearing-in.

This approach moves Ghana from a reactive anti-corruption model — one that prosecutes after damage is done — to a preventive framework that blocks the unqualified and the compromised from public service altogether.

Other nations already do this effectively. In Singapore, public officials are required to make detailed disclosures to the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB), whose oversight is both confidential and uncompromising. South Korea’s Public Service Ethics Act demands annual declarations cross-checked against tax and property databases. And in the United Kingdom, ministers and senior civil servants must submit conflict-of-interest statements to independent ethics advisers, with sanctions for omissions.

The FBI model used in the United States is just one example; these systems share a simple philosophy — prevention is stronger than prosecution.

The Economics of Integrity

Corruption is not merely a moral failing; it is an economic inefficiency. It inflates project costs, distorts market competition, and deters both local and foreign investment. Investors watch governance standards the way bond traders watch inflation — with acute sensitivity.

When public officials’ wealth cannot be explained or verified, markets lose confidence in the institutions that regulate them. Conversely, a BNI-certified asset declaration system would tell citizens and investors alike that Ghana is serious about transparency.

Integrity is not an abstract virtue — it is economic capital. Clean governance reduces transaction costs, increases investor confidence, and raises the credibility of national institutions.

The Moral Imperative

There is also a deeper moral truth. Public service is not a private opportunity; it is a public trust. To hold office is to place one’s personal interests in escrow — to say, “I have nothing to hide, and I invite scrutiny.”

If heaven, as the saying goes, is for the pure in heart, then public office should be for the transparent in assets. A BNI-certified declaration process is not just the best way to clean governance — it is the only way to it.

No assets, no office. The only way to heaven.

Hene Aku Kwapong is a CDD Ghana Fellow, a former Wall Street executive, and Founder of the National Blue Ocean Strategy Initiative (NBOSI – nbosi.org). An MIT-trained engineer, his commentary focuses on institutional reform, transparency, and the economics of public trust.

The post No assets, no office: How NIB can clean up public service appeared first on The Business & Financial Times.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS