Several parties to the Central African Republic's peace accord have yet to sign the much-trumpeted deal, a minister said on Thursday.

The accord was signed in the capital Bangui on Wednesday by militia leaders and President Faustin-Archange Touadera, but its contents have not been disclosed.

"You cannot publish a document until everyone has signed," government spokesman and communications minister Ange Maxime Kazagui told AFP on Thursday.

"There are still three signatures" needed, he said, without identifying the individuals or their affiliation.

Those signatures could be made during the upcoming summit of the African Union (AU), taking place in Addis Ababa on February 10-11, he said.

If so, the accord, named the Khartoum Agreement after the city where it was brokered, will be published afterwards, he said.

The accord was reached in the Sudanese capital at the weekend by the CAR government and 14 armed groups.

The deal is the eighth attempt in nearly six years to forge peace in the war-ravaged country -- one of the poorest in the world.

The conflict has left thousands dead and forced a quarter of the population of 4.5 million from their homes. The rural exodus, the UN warned last year, could drive the country into famine.

One of the biggest obstacles to peace has been demands by rebel leaders to be amnestied -- a condition that Touadera, under pressure from western partners, has traditionally refused.

Several leaders face UN sanctions or have been accused by rights groups of abuses, and others face the notional risk of arrest in CAR itself.

Lack of clarity about the Khartoum Agreement on Thursday prompted a rights organisation, the Civil Society Working Group on the Central African Crisis (GTSC), to urge the government to publish the details.

"In the absence (of these details), the GTSC calls on the Central African people to stage mass protests to press the ruling elite to publish the agreement," it said.

The CAR's descent into crisis began in 2012, when a predominantly Muslim movement, the Seleka, rose in the north of the country.

The following year, the rebels overthrew President Francois Bozize, a Christian, which led to the formation of mainly Christian militias called the anti-Balaka.

France, the former colonial ruler, intervened militarily under a UN mandate, and the Seleka were forced from power.

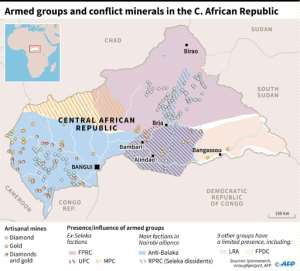

Map showing armed groups and mineral wealth in the Central African Republic. By Thomas SAINT-CRICQ (AFP)

Map showing armed groups and mineral wealth in the Central African Republic. By Thomas SAINT-CRICQ (AFP) Touadera, a former prime minister, was elected president in February 2016, but controls just a fifth of the country,helped by a large UN peacekeeping force.

Militia groups, often portraying themselves as defenders of a community or religious group, control the rest of the territory, often fighting over control of mineral resources.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS