Ghana's economy posted a robust 7.4 percent growth rate in 2018, but up to one third of the country's lenders have disappeared from the financial landscape since the start of 2019, according the African weekly Jeune Afrique .

The influential publication reports on its website that the shutdowns are the outcome of a directive from the Bank of Ghana handing credit agencies operating in the country until 31 December to either raise their minimum capital to 400 million Cedi (72.3 million euros) or face closure.

A press release posted on the Central Bank's website states that out of the 34 lenders operating in the country prior to the directive, only 23 managed to meet the conditions.

Bad loans

Ghana's Finance Minister Ken Ofori-Atta announced earlier this month that up to 11 banks struggling with bad debts and shortage of liquidity had folded up or opted for mergers.

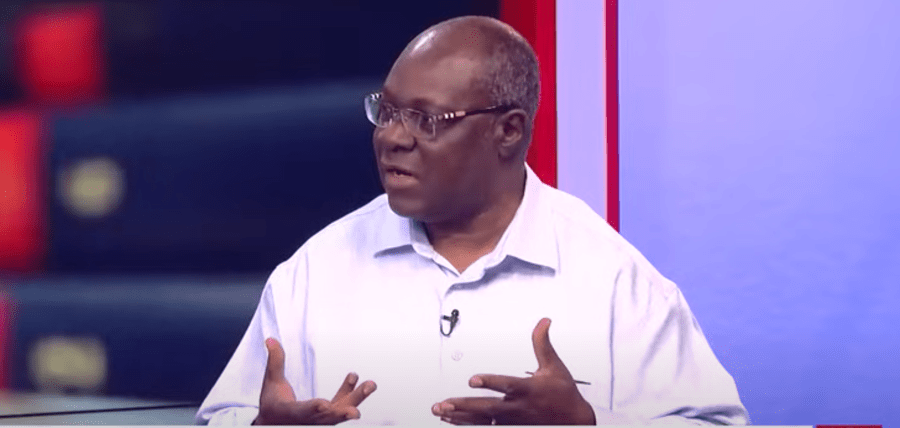

Professor Peter Quartey is Head of the Economics Department at Ghana University in Accra. He says those that defaulted were mostly indigenous banks governed by cronies, friends or families and giving out loans without proper procedures.

Bail out

Quartey welcomed the capitalisation of five public indigenous lenders under a GH¢2.0 billion Ghana Amalgamated Trust arrangement – which he said have good governance structures and are well run but couldn't raise the minimum capital.

The beneficiaries are Agricultural Development Bank, the National Investment Bank, OmniBank Ghana Limited/Bank Sahel Sahara Ghana, the Universal Merchant Bank and Prudential Bank.

“This is something that should have been done in 2016, when a banking sector report showed that the capital base of lenders was eroding very rapidly”, observes the Ghanaian economist.

Interest rates

Professor Quartey singles out the issue of high interest rates as a challenge to Ghana's economy, recalling the time when the state used to borrow from the banks at rates of between 24 to 26 percent.

Now according to the Ghanaian economist, the credit rates have come down to as low as 13 to 14 percent, with inflation running at around 9.2 percent – down from 17 percent.

Quartey argues that such conditions, coupled with the government's reluctance to worsen the total public debt stock (which reached GH¢154 billion – equivalent to 70.50 percent of the country's Gross Domestic Product in 2017), has sent a strong signal to the private sector and to banks not to increase their lending rates.

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS