Rates of female genital mutilation among girls under 14 have fallen sharply in most regions of Africa over three decades, according to ground-breaking analysis cautiously welcomed by aid groups.

The age-old ritual of cutting or removing the clitoris of young females has been decried by human and women's rights advocates and can lead to a host of physical, psychological and sexual complications.

And yet it remains widespread in parts of Africa and the Middle East.

Historically, rates of FGM have been high in East Africa. In 2016, for example, the UN children's agency said 98 percent of women and girls in Somalia had been cut.

But the new research suggests the practice has been falling over time in younger children, the most at-risk group.

While still endemic in many societies there is a growing stigma attached to the practice, making it hard for researchers to get a good idea of whether FGM has remained stable or is in decline.

A team of scientists based in Britain and South Africa conducted the most sophisticated statistical analysis of FGM rates, covering 29 countries and stretching back to 1990.

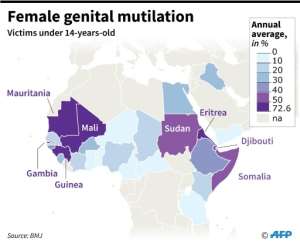

Percentage of girls under the age of 14, in selected countries, who are victims of genital mutilation.. By Simon MALFATTO (AFP)

Percentage of girls under the age of 14, in selected countries, who are victims of genital mutilation.. By Simon MALFATTO (AFP) They drew upon data from two distinct surveys encompassing close to 210,000 children, carried out for the Demographic Health Survey and UNICEF.

After combining the data and eliminating repeat cases, they found a "huge and significant decline" in the prevalence of FGM in under-14s across several regions.

Populous East African nations such as Kenya and Tanzania with low FGM rates -- 3 to 10 percent of girls each year -- ensured a sharp downward trend across the region.

In Eritrea, however, an average of 67 percent of girls were subjected to the procedure each year between 1995-2002.

'Public health priority'

The team determined that FGM prevalence in girls in East Africa fell from 71.4 percent in 1995 to just 8 percent in 2016.

"Recent estimates show that more than 200 million women and children around the world have undergone FGM," Ngianga-Bakwin Kandala, professor of biostatistics at Britain's Northumbria University and lead study author, told AFP.

"Preventing FGM should be a major public health priority in countries and regions still showing a high prevalence among children."

Other regions in Africa saw similar falls in FGM rates over time.

In West Africa the decline was less pronounced but still significant: from 73 percent in 1996 to a little over 25 percent in 2017.

But the study, published Wednesday in the BMJ journal, found that FGM rates in Middle Eastern nations -- including Yemen and Iraq -- had increased.

Naana Otoo-Oyortey, executive director of the anti-FGM charity Forward not involved in the research, told AFP the study would prove "critical in providing insights on reduction in the prevalence of FGM within the 0-14 year group".

But she said it painted an incomplete picture as in some nations, new laws banning FGM might simply be stopping families reporting the practice, rather than abandoning it altogether.

"It is vital that prevalence statistics are accompanied by a contextual and nuanced analysis of shifts in attitudes towards FGM across these countries," said Otoo-Oyortey.

'Challenge social norms'

Jamillah Mwanjisi, head of advocacy, campaigns and media for Save the Children Somalia/Somaliland, without commenting on the study, said FGM remained a major problem.

"We don't have a clear-cut law that says FGM is a criminal offence against children," she told AFP, without commenting on the study's findings.

"In Somalia there's a lack of really strong political will to challenge the social and cultural norms."

Mwanjisi did say, however, that she had witnessed a small fall in the number of 15-17 year-olds who had been cut -- from 98 percent two years ago to 90 percent currently.

This suggests there may be a data lag when it comes to FGM, and that as rates among under 14s drop, we may see a corresponding fall in the overall proportion of women subjected to the procedure.

"The data provided in this study may not answer the question why rates of FGM have fallen," said Kandala.

"Probably mothers' attitude is the main factor, but to answer this question more accurately further studies and data collection is needed."

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS