China on Tuesday defended its controversial decision to ease a 25-year ban on trading tiger bones and rhinoceros horns after conservationists warned that the government had effectively signed a "death warrant" for the endangered species.

The State Council, China's cabinet, unexpectedly announced on Monday that it would allow the sale of rhino and tiger products under "special circumstances".

Those include scientific research, sales of cultural relics, and "medical research or in healing".

The country's previous regulations on rhino horn and tiger bone products did not consider the "reasonable needs of reality", such as those from scientific research, education and medical treatment, foreign ministry spokesman Lu Kang said Tuesday.

China has also improved its "law enforcement mechanism" and plans to step up efforts to crack down on illegal wildlife trade, Lu said at a regular press briefing.

China prohibited the trade of rhino horn and tiger bones in 1993 but a thriving transnational black market has since flourished.

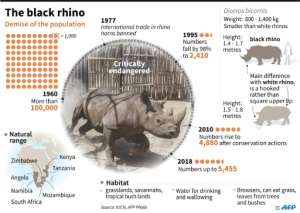

Factfile on the black rhino of southern Africa.. By Kun TIAN (AFP)

Factfile on the black rhino of southern Africa.. By Kun TIAN (AFP) Wildlife campaigners fear the new rules could fuel the illegal trade and further put the animals at risk of being poached.

"With this announcement, the Chinese government has signed a death warrant for imperilled rhinos and tigers in the wild who already face myriad threats to their survival," Iris Ho, senior wildlife programme specialist at Humane Society International, said in a statement.

But the State Council said the trade volume will be "strictly controlled", with any sale outside of authorised use to remain banned.

The newly sanctioned areas of trade will also be highly regulated.

Only doctors at hospitals recognised by the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine will be allowed to use powdered forms of rhino horn and tiger bones.

Tourism and cultural heritage authorities will also have to approve any rhino and tiger products that are used for "temporary cultural exchange".

'Total outrage'

Despite a lack of scientific evidence, demand for rhino horn and tiger bone is partly driven by their supposed health benefits, from curing cancer to boosting virility.

Rhino horn is made from keratin, the same substance that comprises hair and fingernails.

Today, synthetic alternatives exist for a number of animal-based remedies, such as bear bile, which is effective in treating liver cancer.

"The use of wild animal parts such as rhinoceros horns and tiger bones is very limited in the traditional Chinese medicine," Lan Jirui, a traditional Chinese medicine doctor in Beijing, told AFP.

"It was used in ancient times, but now we have alternative products," he said.

Only parts from farmed rhinos and tigers can be used for medical research or treatment, the council said, excluding those raised in zoos.

In Africa, which has seen its rhino populations decimated by poaching, there was a mixed response to China's announcement.

Pelham Jones, chairman of South Africa's Private Rhino Owners Association, welcomed the move, saying that the ban had "aided a massive, transnational illegal trade".

Jones and other owners who have amassed significant quantities of horn after removing their animals' horns to make them less attractive to poachers hope they can now sell those stockpiles legally.

But others were skeptical.

Joseph Okori, an independent conservation expert formerly of the WWF Africa rhino programme, said China's move was "baffling" because it would give the black market a legal avenue for the smuggling of illicit goods.

"I believe it is going to serve to increase, perpetuate the wildlife trade and crime," he said.

In 1960, there were an estimated 100,000 black rhinos in Africa -- today there are fewer than 28,000 rhinos of all species left in Africa and Asia, according to a 2016 UN World Wildlife Crime Report.

Southern white rhinos are "near threatened" but others such as black and Sumatran rhinos are critically endangered, according to WWF.

Up to 6,000 captive tigers -- twice the global wild population -- are estimated to be in held in about 200 farms across China.

China has made efforts to crack down on the sale of illegal wildlife products such as ivory in recent years.

The country's ban on ivory sales went into effect in December 2017 -- an attempt to rein in what used to be the product's largest market in the world.

A partial ban on ivory had already resulted in an 80 percent decline in ivory seizures entering China and a 65 percent drop in domestic prices for raw ivory, according to a report last year by state media Xinhua.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS