In recent years, Ghana has faced a growing environmental crisis that threatens not only the ecosystem but also the foundations of national and business security.

When rivers are poisoned, farmlands degraded, and air quality compromised, the effects extend far beyond the environment — they affect livelihoods, public health, and economic stability. Environmental security is therefore not an abstract concept; it is a national safety issue, a business concern, and a community survival imperative.

Across mining communities in the Western, Ashanti, and Eastern regions, illegal mining — popularly known as galamsey — has polluted rivers that once served as vital water sources.

The Offin, Pra, and Ankobra rivers now carry high concentrations of mercury and cyanide, threatening both human health and agricultural productivity. Fisherfolk who once depended on these waters have lost income; farmers find their soils barren; and entire communities face chronic exposure to toxins.

The economic consequences ripple outward. The Ghana Water Company spends millions monthly on water treatment, while downstream businesses — breweries, food processors, and hospitality firms — bear additional costs to purify water and ensure compliance with health standards. What began as environmental neglect has evolved into a business-sustainability crisis.

A similar trend is visible in urban areas, where poor waste management and unchecked plastic pollution clog drains and intensify flooding. Every rainy season, small traders, shop owners, and transport operators lose livelihoods as flash floods sweep through marketplaces. These are not acts of nature alone — they are symptoms of unpreparedness and a lack of environmental responsibility.

The contrast between environmental neglect and stewardship is clear in two Ghanaian communities. In one district of the Western Region, a cluster of unregulated gold-washing pits collapsed after heavy rains in 2023, killing miners and contaminating nearby farms. The disaster forced the evacuation of dozens of households, and local businesses that supplied food and fuel to the miners collapsed overnight. It was a tragedy born from short-term profit and long-term blindness.

In another part of the country, however, a small cocoa-growing community in the Eastern Region partnered with scientists from the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to rehabilitate degraded farmland.

By reintroducing shade trees, controlling chemical use, and re-training youth as eco-guards, they restored soil fertility and improved cocoa yield by 30 percent within two years. The project attracted private-sector buyers who paid premium prices for sustainably grown cocoa. Environmental awareness became not only a survival tool but a business opportunity.

Science must now take centre stage in Ghana’s environmental-security agenda. The country’s scientific community has the expertise to mitigate damage caused by illegal mining, toxic waste, and climate-induced disasters. The challenge is to connect laboratory research with field application.

For instance, Ghanaian researchers could pioneer affordable technologies for mercury-free gold extraction or bio-filtration systems to clean polluted rivers. Agricultural scientists can develop crops that tolerate degraded soils while gradually restoring them. Environmental engineers can create early-warning systems for floods and air-quality alerts.

The private sector has a pivotal role to play in funding and piloting such innovations. Banks, insurers, and manufacturing firms stand to benefit directly from cleaner, more stable environments that reduce operational risks. Corporate social responsibility should evolve from donation drives to strategic environmental investments — protecting both the planet and profit margins.

For the business community, environmental degradation translates into tangible operational risks: interrupted supply chains, health-related absenteeism, property damage, and reputational loss. A company that ignores its environmental footprint risks regulatory penalties, consumer backlash, and investor withdrawal.

Forward-thinking firms are beginning to integrate environmental management into corporate governance. They conduct impact assessments, adopt green procurement policies, and train employees on sustainable practices. In sectors like construction, manufacturing, and agriculture, environmental diligence is fast becoming a competitive differentiator.

Moreover, insurance companies are re-evaluating coverage conditions. Policies increasingly require businesses to demonstrate compliance with environmental standards before claims are honoured. The message is unmistakable: resilience and responsibility now go hand in hand.

Environmental security begins with public consciousness. Many communities unknowingly contribute to their own vulnerability — dumping refuse into drains, burning plastics, or encroaching on waterways. Education, therefore, is as critical as enforcement.

Traditional and religious leaders can mobilize community action, while schools can incorporate environmental stewardship into civic education. Youth groups, especially in mining and farming zones, can be trained in environmental monitoring and restoration techniques. When people understand that protecting the environment also protects their income and health, change becomes sustainable.

Addressing environmental insecurity requires collective effort. Government agencies such as the EPA, Forestry Commission, and NADMO must coordinate more effectively with the private sector, academia, and civil-society organizations. Businesses can sponsor research, support reforestation, or integrate waste-recycling programs into their operations.

Local assemblies can enforce sanitation by-laws and incentivize eco-friendly practices among traders and transport operators. Media platforms — including business publications like BFT — can amplify success stories and expose practices that endanger collective wellbeing.

Environmental degradation is no longer just a conservation issue; it is a national-security and business-continuity concern. Every polluted river, every illegal dump site, every tree cut without replacement weakens the foundations of Ghana’s development. Conversely, every company that manages waste responsibly, every community that restores a wetland, and every scientist who finds a cleaner solution strengthens our shared security.

Protecting the environment is not charity — it is enlightened self-interest. The more we invest in ecological stability today, the safer, healthier, and more prosperous Ghana becomes tomorrow.

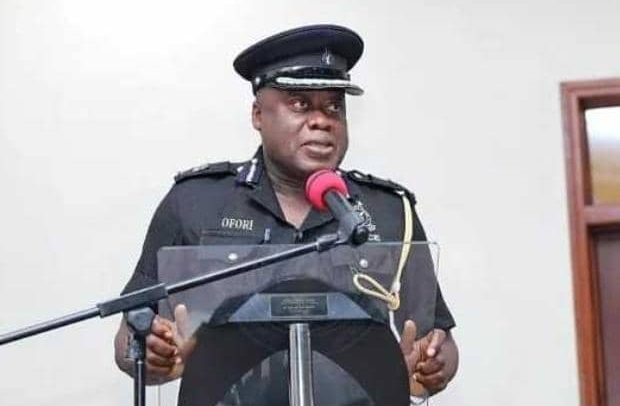

The writer is a Certified Protection Professional and former Director-General, Police Public Affairs Directorate and CEO of MISORNU SAFETY CENTER ,a Ghanaian-based NGO dedicated to promoting and developing a Security and Safety Awareness culture at the individual, community, and corporate levels

The post Security Awareness with David EKLU (DCOP (Rtd): Protecting the environment, protecting ourselves: Why environmental security matters for business and community safety appeared first on The Business & Financial Times.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS