As we continue the series, do refresh your memory by reading last week’s part 1. In Episode 1: ‘When The Pied Piper of Jazz Came to Town’, you recall I gave a brief account of the sights and sounds preceding the Wynton Marsalis Concert in Accra Ghana.

What I did not mention were the number of hopeful musicians hanging around the entrance desirous of a free pass into the venue, but were prevented by hefty, intimidating bouncers specifically hired to prevent non-ticket holders from entering the venue.

I recall in particular a group of about eight young guys all dressed in black, each brandished with either wind or brass instrument encased in leather bags. They were moving from the car park to venue entrance, some on their phones trying to reach an influential person inside the venue to solicit free passes; others trying to “cutesy” their way into the venue by coaxing the bouncers, all to no avail.

Watching this brass band “hustle” to get into the venue without tickets was somewhat amusing. It seemed each had deliberately come along with a spectacle of instruments of different shapes and sizes, hoping the evidence that they were horns men would be valid reason to be granted free passes into the venue.

Unfortunately their spectacle did not move the bouncers. Later, it got me thinking: The fact that regular horns men, Jazz enthusiasts would have to hustle and put up a spectacle just to gain entrance into a Jazz venue to watch their icon immediately points to the downside of Jazz as a high-class status symbol.

Weren’t these group of horns men similar to the very types of people that started playing Jazz as an Art form of Black people over a century ago when Jazz emerged in New Orleans? Back then, Jazz brought together musicians in Juke Joints, speakeasies and the like…They expressed raw talent, passion for the art, entertained freely . But today, a century later, those same type of people are not qualified to gain entry into a Jazz venue because they could not pay the requisite gate fee?

Talking about the gate fee, “Eeeh can Ghanaians afford that!”, exclaimed a certain musician when I told him the cost of the tickets I bought . “Well..” , I replied “…the Wynton Marsalis Concert was not targeting the typical Ghanaian.. In fact the people that attended were not typical Ghanaians”, I explained further. I saw Ghanaians who had obviously lived abroad, Members of the Diaspora, large groups from the African-American community in Ghana, diplomats, ambassadors, Europeans and persons from the ‘upper class’. Again, this points to another downside of Jazz as a high-class status symbol: It cuts off a significant portion of music enthusiasts and caters only to a select elite few.

When Jazz emerged in the early 1920s , its black musicians were in a very vulnerable position. They were subject to white supremacy, segregation and Jim Crow Laws. While their earlier enslaved ancestors on Southern Cotton Plantations had field songs and Negro Spirituals to entertain and comfort them, Jazz provided these musicians an escape, comfort, a vehicle for resilience and a means to protest civil rights. Musicians who had opportunity to receive better remuneration while performing to white audiences did so knowing that they could either water down their civil rights activism or use those platforms to speak to the “Powers that be”.

So while it gave Jazz more credibility and legitimacy, the evolving of Jazz into high-class status symbol silenced a lot of the civil rights activism of several musicians, because if they wanted to flourish financially and commercially they could not be associated with challenging their White Supremacists. Those musicians that refused to be silent, such as Billie Holiday, Nina Simone, paid a price. They were either jailed, sanctioned by the authorities or had their music taken off air and lived miserably.

In any case Black musicians who benefitted financially from Jazz evolving into high-class status symbol were still treated like 2nd Class citizens.

Nat King Cole was an enormously popular crooner, earning US$4,500 a week in Las Vegas in 1956. He headlined at the whites-only Thunderbird Hotel, where he wasn’t allowed to venture beyond the showroom and the cook’s resting area behind the kitchen. Cole’s road manager was given a room in the hotel because he was white, but the high-paid main feature attraction had to find other accommodations.

Nat King Cole regularly stayed in a rooming house on the West Side. It was said that Frank Sinatra later intervened and Nat King Cole was given same treatment as his white counterparts. But would Nat King Cole have received improved treatment if his music was openly associated with civil rights activism?

While some criticised him as an “Uncle Tom”, others have argued in his defense that “beneath the polished veneer of his public image lay a deeply personal commitment to confronting racism and advocating for equality that is often overlooked”. But this is a discourse for another day.

These are my personal opinions; and after conducting further research on the topic, I discovered there are more downsides to Jazz becoming a high-class status symbol, viz:

- Loss of edge – By becoming respectable, some argue Jazz lost its counter-cultural danger and improvisational rawness. It was institutionalised and formalised in a way that moved away from its roots in Black-American culture.

- Elitism vs. tradition – The emphasis on tradition and academic study can sometimes foster an elitist or gate-keeping attitude among some fans. At the same time, many within academia continue to fight for Jazz to be fully recognised alongside European classical music.

Jazz elitism, the exclusionary attitude that certain forms of Jazz are superior to others, has several disadvantages. It discourages new audiences, stifles creative innovation and alienates musicians who explore other genres.

Disadvantages of Jazz elitism

Deters newcomers and younger audiences

- High barrier to entry – An overly rigid and technical approach to Jazz creates a high barrier for new listeners and musicians, making the genre feel unapproachable. The pressure to understand complex theory or to play “correctly” can intimidate and push away potential fans.

- Exclusionary “rules” – Elitist Jazz fans may create a culture with unwritten “rules” about what is considered legitimate Jazz. This can make newcomers feel unwelcome and can limit the genre’s appeal, reducing its potential for growth.

- Discourages exploration – When Jazz is presented as an esoteric and intellectual art form, it loses its connection to the dance halls and working-class venues where it first gained popularity. Some younger listeners may perceive Jazz as “pretentious,” “snobby,” or “inaccessible” because of the attitude of some of its enthusiasts.

Restricts musical innovation

- Discourages cross-genre experimentation – Jazz elitism often celebrates a narrow, “pure” form of jazz and looks down on artists who experiment with other styles, such as pop, funk or hip-hop. This approach runs contrary to the innovative and collaborative spirit of Jazz’s founders, who often borrowed and experimented with other musical traditions.

- Focus on technicality over emotion – Elitist perspectives often prioritise technical skill and theoretical complexity over artistic expression, emotion or whether the music “sounds good.” This can lead to technically proficient but emotionally hollow music.

- Dismisses newer forms – When the “rules” of Jazz become dogmatic, it becomes difficult for the genre to evolve. Younger or experimental artists who deviate from established traditions may find their work dismissed as “not real jazz”.

Harmful to the Jazz community and artists

- Creates division – Elitism can divide the Jazz community between a powerful few who set the rules and the many who feel powerless and judged. This can lead to a toxic environment, where musicians criticise each other instead of supporting fellow artists.

- Alienates artists – Musicians who are celebrated for their mainstream success or their genre-blending can be dismissed by elitists within the Jazz community. This lack of support can be demoralising for artists who are trying to make a living while also pushing the boundaries of their craft.

Wynton Marsalis is often accused of Jazz elitism and purism due to his strong emphasis on traditional jazz styles and his criticism of more modern or experimental forms, which he believes have deviated from the music’s core principles. Critics argue that his focus on tradition is rigid and can seem dismissive of innovations by artists like Miles Davis and Ornette Coleman, while supporters see his work as vital to preserving Jazz’s history and cultural significance.

- Stifles honest dialogue – An elitist culture can pressure people to conform to certain expressions or viewpoints, discouraging honest and critical conversations. This can prevent the community from addressing underlying issues and from growing in a healthy way.

In conclusion despite its complex history or its high-class status symbol, Jazz continues to experience enduring influence. The improvisational nature and spirit of Jazz continues to inspire creativity and self-expression, influencing countless other genres from rock to pop to hip-hop.

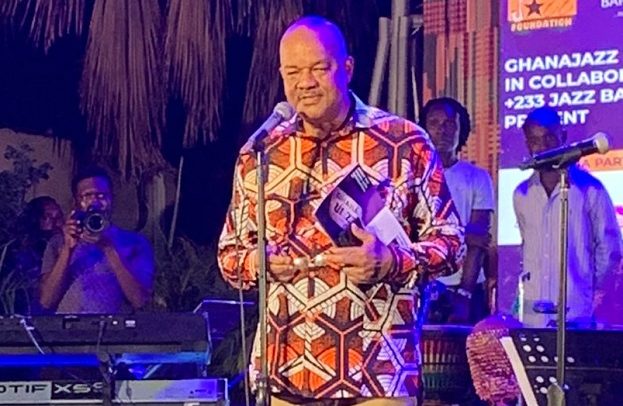

>>>Me & My Jazz are the weekly musings of Jazz Singer & Jazz Radio Host, Yomi Sower. Her programme ‘Maximum Jazz’ airs on Saturdays 4-7PM on Ghana’s Guide Radio 91.5FM. She is a Professional Voice Coach also offering Vocal Jazz Tuition @YomiSower -Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, X and E- mail: [email protected]

The post Me and My Jazz with Yomi SOWER (Episode 4): From trashy to classy: How Jazz became a high-class status symbol (Part 2) appeared first on The Business & Financial Times.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS