By Joseph CUDJOE

In the Biblical story of the Tower of Babel, humanity once spoke a single language. Their unity in communication enabled them to attempt a bold project — building a tower to reach the heavens.

But when their language was confused, they no longer understood one another; the project collapsed and they were scattered. The lesson is timeless: shared language fosters unity and progress; divided tongues create confusion and stagnation.

This ancient insight has a direct bearing on Ghana’s present and future.

The Ghanaian reality

Ghana is blessed with a rich cultural tapestry of over 80 languages. From Akan to Ewe, Ga to Dagbani, Nzema to Gonja, each carries history, poetry and identity. Yet, while diversity is beautiful, when every group clings tightly to its language as a badge of political or ethnic competition, it weakens our ability to act as one nation.

The truth is clear: a nation divided by languages struggles to build together. Imagine a construction site where masons, carpenters and engineers cannot understand one another. Progress stalls, not because of lack of skill, but because of lack of shared communication. That is exactly the danger Ghana faces if we fail to manage our linguistic diversity wisely.

Lessons from other nations

History shows that nations that successfully built cohesion and rapid development usually did so with one widely accepted language of unity:

- Japan and South Korea unified around their native tongues.

- France insisted on French for administration and education.

- Tanzania, closer to home, adopted Swahili as its national lingua franca, allowing over 100 ethnic groups to act as one people.

By contrast, countries that allowed language divisions to become political weapons — often in Africa — remain trapped in cycles of disunity, inefficiency and slower progress. Some may point to Canada, Switzerland, Belgium or Singapore as successful multilingual states. But in these cases, multiple languages are not tribal weapons.

They are institutionally recognised and harmonised within strong national systems. Importantly, there is always a neutral working language (e.g., English in Singapore, German/French in Switzerland) that keeps the nation united in governance, education and economic life.

What this means for Ghana

Ghana cannot afford to let its many languages scatter national effort. If every ethnic group insists on elevating its tongue to the national stage, we risk repeating Babel’s confusion: no shared vision, no united progress. This does not mean abandoning our local languages. They are treasures to be preserved at community and cultural levels. But for nation-building, Ghana must rally around:

- English as the neutral, global-facing working language for governance, education and trade.

- One Ghanaian lingua franca (likely Akan/Twi, given its wide reach) as a cultural bond for unity, used in national broadcasting, arts and early education.

- Regional languages encouraged locally, but without competing for national dominance.

This “dual-language approach” would give us the best of both worlds — the global advantage of English and the cultural pride of an indigenous tongue, without the political fragmentation of unmanaged multilingualism.

The hard truth

If Ghanaians continue to cling to local languages as markers of political power, we will remain a scattered people, struggling to unite for development. The Tower of Babel warns us: language can either build a nation’s tower or scatter its stones. Unity is not about erasing diversity, but about choosing one voice when it matters most. Ghana needs the courage to elevate a common national language policy that prioritises unity, efficiency and progress over ethnic pride and rivalry.

A call to action

The question is not whether Ewe, Ga, Dagbani, Nzema or Twi are valuable — they all are. The real question is: do we want to build together or scatter apart? Ghana’s destiny depends on choosing wisely. Let us learn from Babel and from history. Let us agree on a common path, so that when we speak of building a greater Ghana, we do so in one voice — clear, united and unstoppable.

Oobake, Woezor, Akwaaba …

The afore-mentioned points outlines my take on the Oobake, Woezor and the Akwaaba debate. Since my early school days when I heard the Tower of Babel story for the first time, I have always believed that ethnicity and tribalism as reinforced by languages has been the bane of development of African countries.

Religions have worsened it, but that’s for another day. Unless we face this reality and undertake serious social engineering today to unite the future generations of Ghana and Africa through one or few generally accepted and spoken languages at the national and continental levels, divisiveness and disunity will continue to stall our speedy economic development.

Final words

In summary, if Ghana clings too tightly to fragmented language identities, unity will remain elusive and development slow. But if we rally around a clear language policy, we can finally build our own “tower” — not to challenge God, but to uplift our people.

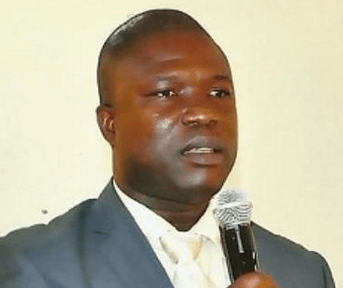

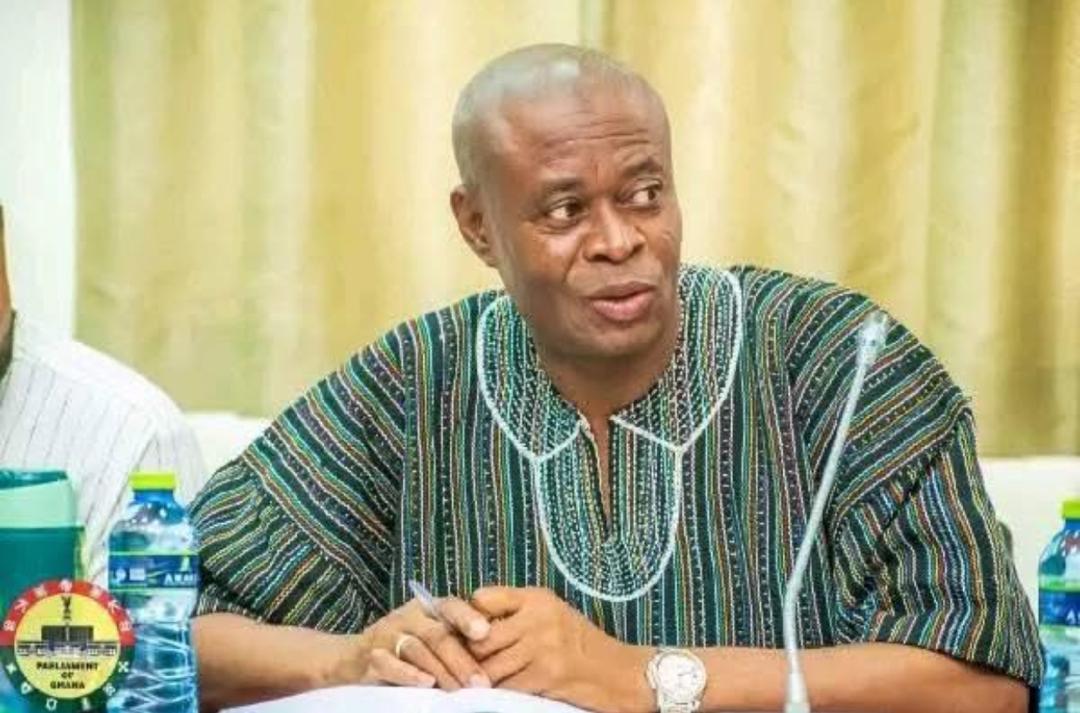

>>>the writer is the former Member of Parliament (MP) for Effia Constituency in the Western Region and a former Minister for Public Enterprises #MEN@WORK

The post Language, unity and development: Lessons from the Tower of Babel appeared first on The Business & Financial Times.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS