By Norman Adu BAMFO

Ghana’s September 2025 inflation rate of 9.4percent marks a symbolic milestone in the nation’s post-crisis economic recovery. For the first time since late 2021, headline inflation has fallen within the Bank of Ghana’s medium-term target band of 8 ± 2percent, signalling a possible stabilization of macroeconomic conditions.

From a de jure standpoint measured by the official numbers this represents a notable policy achievement reflecting the tangible cumulative effects of fiscal consolidation, monetary restraint and exchange rate stabilization.

Yet, beyond the aggregate data lies a de facto reality of uneven outcomes. Structural bottlenecks, regional disparities & asymmetries, and heterogeneous market conditions have produced vastly different inflation experiences across the country.

While the headline number (the national average) suggests restored macroeconomic stability, regional inflation data reveal a fragmented landscape, one that challenges the inclusiveness and depth of Ghana’s disinflation trajectory.

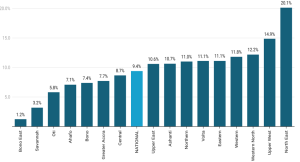

According to the Ghana Statistical Service, inflation across the sixteen regions ranged from a low of 1.2percent in Bono East to a high of 20.1percent in the North East Region. In fact, nine regions (representing 56percent out of the total number of regions) recorded inflation rates above the national average. This wide variance underscores the uneven spatial transmission of policy gains and highlights the persistence of localized vulnerabilities.

- Inflation landscape and regional divergence

The breadth of variation in regional inflation highlights the differentiated nature of Ghana’s economic geography. Bono East’s inflation of 1.2percent, the lowest in the country suggests relative price stability, likely influenced by better access to supply chains, improved infrastructure connectivity, and possibly more efficient market coordination.

In contrast, the North East’s inflation rate of 20.1percent signals a deeply constrained market environment. Structural impediments such as weak road networks, poor storage facilities, and high transport costs amplify supply disruptions, particularly for essential commodities like food and fuel.

Other northern regions, Western North, Upper East, Upper West, and Northern also posted double-digit inflation, reflecting the broader developmental gap between the northern and southern belts. These regional discrepancies are not just statistical anomalies but manifestations of structural asymmetries in market access, production efficiency, and public investment distribution.

Such divergence challenges the assumption that national-level inflation trends accurately capture the lived economic realities across the country. Ghana’s headline figure though commendable therefore represents an aggregate of unequal experiences rather than a uniform national improvement in purchasing power.

- De jure stability vs. De facto fragility

From a de jure perspective, Ghana’s inflation trajectory reflects the visible impact of policy coordination. The Bank of Ghana’s sustained monetary tightening, fiscal consolidation under the IMF-supported program, and exchange rate stabilization have collectively moderated inflation expectations and anchored macroeconomic discipline. This national outcome provides a sense of policy coherence and institutional credibility.

However, the de facto experience of inflation how prices actually evolve in local markets reveals a fragmented picture. In many rural and peri-urban areas, informal pricing mechanisms dominate, and cost adjustments occur independently of official policy signals. Traders in regions with poor connectivity and low competition often price in risk premia to hedge against future supply shocks. This results in persistent price stickiness and inflationary inertia, even when national inflation trends improve.

Furthermore, food inflation, a major driver of headline CPI remains disproportionately high in food-producing regions due to inefficiencies in post-harvest management, transportation, and storage. The paradox of high inflation amid agricultural abundance points to structural constraints that monetary policy alone cannot resolve.

- Drivers of regional disparities

The divergence in regional inflation outcomes across Ghana is rooted in a complex interplay of structural, market, and socioeconomic factors that shape how price pressures manifest in different parts of the country.

A primary driver lies in infrastructure and logistics. In the northern regions, limited transport networks and deteriorating road conditions significantly increase transaction costs and delay the movement of goods.

These inefficiencies raise the final retail prices of essential commodities, as traders pass higher transportation and storage expenses onto consumers. By contrast, the southern and coastal regions benefit from better connectivity and proximity to major markets, resulting in lower logistical costs and more stable prices.

Market structure also plays a defining role. In remote or less integrated regions, lower levels of competition grant traders and intermediaries greater pricing power. With limited alternatives available to consumers, sellers often maintain wider profit margins, perpetuating higher prices even when national inflation pressures subside. Conversely, urban centres such as Accra and Kumasi, characterized by a more competitive marketplace and higher trade volumes, experience faster price adjustments and reduced inflation volatility.

On the supply side, agricultural vulnerabilities remain a persistent source of regional inflation. Dependence on seasonal rainfall, inadequate storage infrastructure, and limited access to affordable credit for smallholder farmers collectively contribute to inconsistent food supply and pronounced price swings.

In times of poor harvest or logistical disruption, these structural weaknesses lead to localized scarcity and sharp increases in food prices often the single largest driver of inflation in Ghana’s northern and transitional zones.

Lastly, income and consumption patterns amplify these regional disparities. In lower-income regions, where food accounts for a greater share of household expenditure, even modest increases in food prices have a disproportionately high impact on the cost of living. Meanwhile, households in urban and higher-income areas, with more diversified consumption baskets, experience a relatively muted inflationary effect.

Together, these factors have created a dual inflation reality in Ghana: one of relative stability in urban and economically diversified centres, and another of persistent price instability and reduced purchasing power in peripheral and agrarian regions.

This divide highlights the structural nature of inflation in Ghana, where national stabilization policies may succeed de jure, but de facto stability remains unevenly distributed across the country.

- Policy Implications and the Path Forward

The coexistence of de jure disinflation and de facto regional inflation divergence carries important policy implications. It underscores that while monetary and fiscal tightening have restored national-level stability, regional policy asymmetry remains a critical challenge.

Addressing these gaps requires a shift from macro-level stabilization to micro-level resilience building. Policies must focus on improving logistics infrastructure, strengthening food supply chains, and enhancing data-driven monitoring of regional markets.

The Ministry of Finance and the Bank of Ghana should collaborate with the local government and the National Development Planning Commission (NDPC) to tailor interventions that reflect regional production structures and consumption patterns.

Moreover, future inflation management should integrate spatial policy frameworks linking transport, agriculture, and trade development to reduce the cost disparities that fuel regional inflation gaps. Targeted investments in rural market infrastructure and cold-chain systems could help align de facto realities with de jure success

- Conclusion:

Ghana’s return to single-digit inflation is a commendable milestone and a testament to disciplined economic management. Yet, beneath this aggregate achievement lies a landscape of unequal price stability. The de jure narrative of macroeconomic progress coexists with de facto fragility in the peripheries an imbalance that risks undermining inclusive economic recovery.

To sustain and broaden disinflation gains, Ghana must go beyond headline stabilization and embrace policies that narrow regional inflation disparities, enhance market efficiency, and strengthen resilience in its most vulnerable regions. True price stability will not only be reflected in the national CPI but also in the everyday affordability and confidence experienced by households across all sixteen regions.

>>>the writer is a seasoned professional in risk, finance, banking, and treasury management with over a decade of academic and industry experience. He holds an MPhil in Finance (UGBS) and a First-Class Honors BSc in Actuarial Science (KNUST), and is a Chartered Global Investment Analyst as well as an ACI-Certified Treasury Professional (Distinction). A member of ACIFMA Ghana, he also holds a Leadership and Management Certificate from IMD Business School, Switzerland. He serves as a Part-time Lecturer at the University of Ghana Graduate Business School and Instructor at the National Banking College. His dual engagement in academia and industry enables him to bridge theory and practice, advancing financial market knowledge, innovation, and governance across Ghana’s banking sector. He can be reached via [email protected] and or 233240402075

The post Single-digit inflation and regional disparities – De jure stability, de facto fragility appeared first on The Business & Financial Times.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS