By John Baptist Walier Kabo-Bah

Sugarcane production started in the 1960s, just after Ghana gained independence in 1957. Asutsuare and Komenda of Cape Coast were noted for sugarcane farming, and later Volta and Eastern Regions joined the league.

The sugar factories at Komenda and Asutsuare in the 1960s were established to drive the industrialisation of sugarcane and support increasing domestic demand.

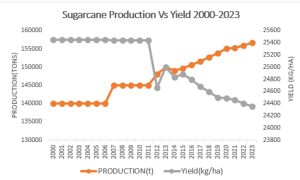

Ghana recorded its highest production in 1977 at 270,000 tonnes, which led to a drop in sugar imports. Regrettably, since the 1980s, Ghana has witnessed a steep decline in sugarcane production—a situation that further deteriorated after 2011 with persistently low yields. Unfortunately, this downward trend has continued unabated to the present day (Figure 1).

When Ghana rebuilt the Komenda Sugar Factory in 2016 with a USD 35 million EXIM Bank of India facility, it was supposed to jumpstart local sugar production and cut down the massive sugar import bill. Instead, the factory barely got past its test run – a satellite study found it could source only about 7% of the sugarcane it needed due to feedstock shortages (Yawson et al., 2018).

Smallholder farmers who supplied cane also baulked at the uneconomical price offered (just GHS 60 per tonne, roughly USD 10), which made it impossible to earn a living. Operations ground to a halt, echoing an earlier era in the 1980s when a high cost of production, water and energy shortages led Ghana’s two sugar factories (Komenda and Asutsuare) to collapse despite a 1977 production peak of 270,000 tonnes (Yawson et al., 2018).

Figure 1, Data Source: (FAOSTAT 2024)

After several start failures, the government led by the former Trade Minister, Hon. K.T. Hammond, announced in August 2024 that Komenda Sugar Factory would be leased to a new strategic investor – West African Agro Limited, an Indian firm, for 15–20 years, as a last-ditch effort to revamp the facility.

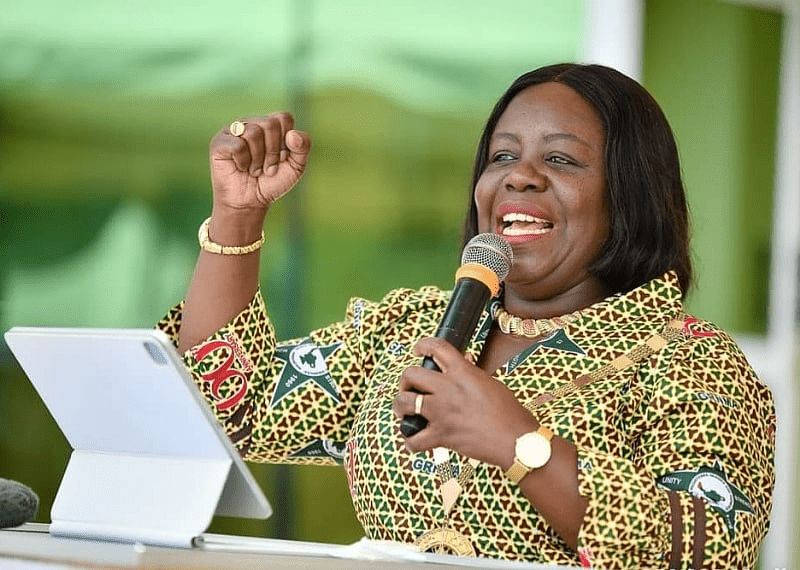

This move initially raised hopes among farmers and many stakeholders. Fast forward to March 2025, the Minister for Trade, Agribusiness, and Industry, Hon. Elizabeth Ofosu-Adjare, underscored the urgent need to revitalise the Komenda Sugar Factory as part of the government’s Industrialisation Agenda when she visited. Notwithstanding, by May 2025, frustration boiled over.

The Sugarcane Farmers Association of Ghana issued a public plea, lamenting that “two months after the Minister’s visit, no visible progress has been made”. The factory wasn’t even mentioned in the 2025 national budget, they noted, and farmers felt “deceived” after rallying behind political promises that Komenda would be revived. The Association demanded immediate action – the appointment of a new board (with farmer representatives) to get the factory running, insisting “we are ready to feed the factory with sugarcane. All we need is government commitment”.

Half-Billion-Dollar Sugar Import Challenge

Ghana currently spends about $500 million every year on imported sugar – a crippling outflow of foreign exchange for a commodity that could, in theory, be produced domestically. The government has signalled that this status quo is unsustainable and unhealthy for economic prosperity. In early 2025, Trade Minister Hon. Elizabeth Ofosu-Adjare reaffirmed plans to “reduce the importation of sugar and enhance local production” by revitalising Komenda. Revamping the factory is not just an industrial goal but part of a broader economic vision.

The Minister highlighted that Komenda will be integrated into a new 24-Hour Economy policy – essentially running the factory around the clock – and supplied with raw materials through a “Feed The Industry” project to guarantee cane for processing. Under this initiative, government funding and support would help local farmers scale up sugarcane cultivation as dedicated suppliers to the factory. The successful implementation of the plan could create an estimated 7,500 jobs in the region and significantly reduce Ghana’s sugar import bill.

However, intentions alone do not automatically translate into results. The Komenda saga so far shows a pattern of ambitious announcements followed by inertia on the ground. As Ghana pushes its “Feed the Industry” agenda as part of a new industrialisation drive, the sugar sector will be a litmus test. Can the government marry policy with practical support to farmers? Can it learn from past missteps and ensure that a 24-hour factory has a 24-hour supply of cane? The answers will determine if Ghana can finally wean itself off costly sugar imports.

Smallholder Sugarcane Farmers at a Crossroads

Whereas policymakers debate plans, Ghana’s smallholder sugarcane farmers live the reality of the industry’s dysfunction. They face multiple challenges that have kept local sugar production at a trickle:

- Unfair Pricing and Market Uncertainty: Farmers have repeatedly experienced broken promises, notably in 2022 when Komenda’s factory management failed to honour purchase agreements, leaving cane unharvested and farmers uncompensated. Plans by the factory to import raw sugar, instead of procuring locally, further eroded trust. The longstanding issue of low, unattractive pricing—exemplified by the 2016 offer of just GHS60 per tonne—continues to discourage farmers’ investment in sugarcane production and heighten farmer vulnerability.

- Information Asymmetry: There is a persistent gap in information and coordination along the value chain. Farmers often lack timely knowledge about the factory’s operational status, cane quality requirements, or market pricing. Decisions are frequently seen as top-down. The 2024 lease announcement, for instance, came and went with scant engagement with cane growers on how they would be integrated. This information void leaves farmers unable to plan their production – many only learned through media that an investor might take over, and months later, through painful silence, that nothing had changed, neither in the factory nor on their farms. The sugar industry’s history is currently littered with missed signals. Drawing on the work of Matt Andrews and Lant Pritchett, it is evident that many policy failures in developing contexts are rooted in entrenched information asymmetries and a systemic lack of adaptive policy learning. Hence, bridging these gaps is critical to revitalise the sector. Farmers need transparent communication channels and inclusion in decision-making to avoid past mistakes.

- Climate and Agronomic Risks: Sugarcane is a water-intensive crop, yet most Ghanaian smallholders rely on rain-fed cultivation. Climate variability – erratic rainfall patterns, prolonged dry seasons, and occasional floods – poses a growing risk. The Komenda factory’s flop in 2016 was in large part because there was simply not enough cane to crush; a key reason was the lack of irrigation to cushion dry-season shortfalls. Yields suffer when rains are delayed or drought hits, and climate change is making such events more frequent. Additionally, without access to improved cane varieties or modern agronomic practices, smallholders struggle to achieve high productivity. Pests, diseases, and soil nutrient depletion further threaten their output. These climate and agronomic challenges mean that any serious sugar policy must include climate-smart, resilient farming methods – from introducing drought-tolerant cane breeds to providing irrigation infrastructure.

- Weak Institutional Support: Smallholder sugarcane farmers in Ghana lack institutional backing, including dedicated extension services, formal training, and accessible credit facilities. Cooperative associations like the Sugarcane Farmers Association exist but struggle for recognition and influence in decision-making. Persistent policy inconsistencies—shifts between local procurement and import reliance—have fostered mistrust and kept farmers vulnerable in the region, resulting in chronic low productivity. Stronger institutions, coherent policies, and effective farmer participation are urgently needed.

Lessons from Africa’s Sugar Producers

Effective integration of smallholder farmers into Africa’s sugar value chain is no longer just an aspiration—it is increasingly recognised as a foundation for industrial transformation and rural empowerment. Recent country-specific studies shed light on the practical mechanisms that underpin success across Egypt, South Africa, Eswatini, and Mauritius, etc. providing actionable lessons for policymakers and investors alike.

Egypt is showing what’s possible when smallholders are equipped with the right tools and support. Recent research highlights how state-backed extension services and public-private partnerships have given farmers better access to seeds, fertilisers, and reliable markets. This hands-on approach has pushed up average sugar yields while cutting input costs according to (El-Din & Rabie, 2024). Behind these gains, clear government procurement frameworks and proactive farmer education have given smallholders the confidence and resources to scale up.

South Africa has built one of the continent’s most sophisticated sugar systems, anchored by a cane pricing structure that rewards quality and stability. According to the 2023 Sugar Industry Value Chain Master Plan, this approach insulates small growers from global price swings and fosters reinvestment in their farms. Recent field research reports that more than 65% of South African smallholders have boosted their technical know-how and farm management skills through robust extension services, turning what was once a vulnerable sector into a reliable engine for rural growth.

Also, case studies from SAP and the Royal Eswatini Sugar Corporation show that modernisation efforts (including irrigation and digital agronomic support) have supported over 4,000 smallholder out-growers, boosting yields, lowering costs, and increasing forecast accuracy, confirming the effectiveness of public–private collaboration. This transformation has been mirrored by visible gains in rural household incomes and local employment.

Mauritian sugar industry’s evolution is championed through cooperative frameworks, supported by sustained government investment in research and farmer services, which have enabled smallholders to leverage economies of scale and access premium export markets. The 2023 implementation review of the Plan reports that 80% of smallholders surveyed had benefited from improved access to credit and mechanised services, resulting in enhanced productivity and sustainable land use practices (Mauritius Cane Industry Authority, 2023).

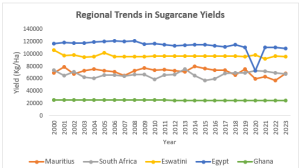

Ghana’s sugarcane yields have remained persistently low and stagnant, hovering just above 20,000 kg/ha from 2000 to 2023, while peer countries such as Egypt, Mauritius, Eswatini, and South Africa consistently achieve yields two to five times higher (Figure 2). This pronounced and unchanging yield gap underscores significant structural and systemic challenges in Ghana’s sugarcane sector—including limited access to improved inputs, technology, and extension services—highlighting an urgent need for targeted policy interventions and adoption of best practices to unlock Ghana’s potential and bring its productivity closer to regional standards.

Figure 2, Data source: (FAOSTAT 2024)

Historically, sugar production in Ghana has struggled due to fragmented supply chains, limited farmer engagement, and reliance on imports, undermining local production capacities and stifling rural economic growth. Yet, these challenges also present opportunities for meaningful transformation—one that prioritises smallholder farmers, boosts local industry, and builds resilience against global market shocks.

These experiences with peer countries collectively show Ghana that by adapting proven strategies, Ghana can accelerate its journey towards sustainable sugar production and rural prosperity, and food sovereignty.

My internationally recognised and award-winning sugarcane development model-Sugarcane Food Forest Programme, champions a practical, scalable model designed to transform smallholder farming into a resilient, high-yield, and market-driven system. Drawing on both research and practical experience within Ghana’s agricultural context, the model elevates smallholder sugarcane farmers from the status of mere suppliers to that of strategic partners, central to the long-term sustainability and competitiveness of the entire sugar sector. By prioritising collaborative structures, equitable benefit-sharing, and continuous capacity-building, the model not only aligns with but would also support and amplify the government’s initiatives, such as Feed Ghana, Farmer Service Centres, and the ambitious 24-Hour Economy policy, including the Grow24 framework. Leveraging the round-the-clock opportunities offered by Grow24, the model will drive a more dynamic and integrated value chain, generate expanded employment opportunities, and accelerate rural industrialisation—ultimately supporting Ghana’s transition from import dependency to self-sufficiency.

To realise this vision, robust collaboration among the government, private sector, civil society, and farming communities is indispensable. Strategic investments in climate-smart irrigation, digital agricultural innovation, and inclusive market systems—anchored in my award-winning model—are vital for unlocking productivity, profitability, and resilience across the sugar value chain. Accordingly, I extend an open invitation to government officials, industry leaders, and development partners to engage in substantive dialogue and collaborative partnership. Together, by drawing on my model and the momentum of policies like Grow24, we can reimagine Komenda Sugar Factory not as an idle facility, but as a vibrant engine of inclusive growth and a source of pride for all Ghanaians. Let us reignite the future of Ghana’s sugar sector—driving sustainability, inclusivity, and innovation at every stage of the value chain.

The author is a Business Development Strategist & Agribusiness Management Professional)

The post From dormancy to opportunity: Positioning Komenda Sugar Factory appeared first on The Business & Financial Times.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS